Kerry Howley

The twenty-first-century critic asked to opine on masculinity finds available to her a limited number of explanatory templates, socially acceptable ways of speaking that dominate our collective thinking about the male psyche. Most clearly, there is that of disapproval, talk of privilege and patriarchy and, of late, the much-deployed “rape culture.” There is also the moralizing template, preferred by presidential candidates and megachurch pastors, which merely ascribes desirable qualities to the state of being a man, generally preceded by the descriptor “real”: Real men raise their children, real men don’t cheat, real men, I don’t know, exercise portion control. For

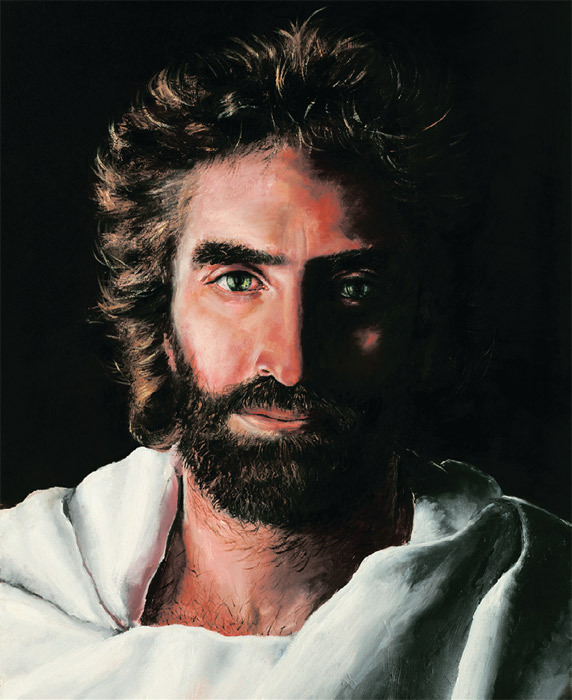

It is the unfortunate fate of many women of a certain period to be recalled not as individuals but as “flappers,” a word that seems, to modern chroniclers, a nearly irresistible invitation to a morality tale. A woman of the 1920s might refuse domesticity without consequence; a flapper, on the other hand, will burn brightly for a time before descending into the kind of callow, knowing narcissism that completes a particular narrative arc. We know many of these stories by heart: Zelda Fitzgerald fell into madness, and Tamara de Lempicka into obscurity. Tallulah Bankhead was a drunk, Josephine Baker never Navy SEALs during parachute training. After giving the order for twenty-four Navy SEALs to descend upon a compound in Abbottabad in April of 2011, President Barack Obama attended the White House Correspondents’ Dinner, where he addressed many of the same people the White House would rely upon to propagate its version of the raid. This […] Lakewood Church senior pastor Joel Osteen’s second book, Become a Better You, reportedly made him $13 million; his latest, I Declare (FaithWords, $22), is now on USA Today’s best-seller list. Osteen came to lead the country’s most mega megachurch by selling a feel-good message about the relationship between positive thinking and a life well lived. “Explosive blessings,” Osteen tells his congregation, come to those who “speak victory.” Osteen fans, who include Oprah Winfrey, Hulk Hogan, and Cher, are instructed to “develop a habit of happiness.” And while some critics quibble with the pastor’s parroting of the prosperity gospel, and others

The amateur writer of women’s erotica may be forgiven for thinking, as she pushes her manuscript upon Siren Publishing, Ellora’s Cave, and Carnal Desires, that she has finally entered a freewheeling realm of sexual exploration, an oasis of untrammeled erotic fantasy. She may continue under this impression as she scans the retail horizon, landing upon titles like Tall, Dark and Dominant, Male Android Companion, Two Men in Her Tub. But she is bound to be disabused when she stumbles upon the Guidelines for Submission, written always in that tone of world-weary prophylactic disappointment, and learns precisely what is not welcome.

“As smoking gives us something to do with our hands when we aren’t using them,” Dwight Macdonald wrote in 1957, “Time gives us something to do with our minds when we aren’t thinking.” What leads us here, Macdonald asks, to the banal, boxed trifles of popular journalism? What, exactly, is to be gained by a three-hundred-word once-over of “World News”? Do we seek, as Macdonald concedes to be Time’s singular benefit, “practice in reading”? Perhaps we crave immersion in a warm bath of facts, to “have the little things around, like pets,” to collect “them as boys collect postage stamps.”

Thomas De Quincey’s “The English Mail-Coach,” an essay that begins as a jaunty paean to the English postal system and ends in drug-fueled nightmare, appeared, in 1849, in Blackwood’s Magazine. That is to say, a reader picking up the general-interest journal would have plunged into what appeared to be a winking disquisition on mail-coaches only to come, many pages later, to a subheading titled “Dream-Fugue: Founded on the Preceding Theme of Sudden Death,” at which point he would be firmly planted in an opium addict’s waking fever. The mail-coaches of his youth warranted lengthy description, wrote De Quincey, because they In his new book, Paco Underhill, a longtime student of consumer behavior, evinces a particular aversion to the word woman. He prefers instead “the female of the species” or “the female of the household” or “the female of the house.” The female of the species, we learn, behaves in a specific, predictable way in hotel lobbies. The female of the species feels about her kitchen the way the male feels about his car. The female of the species prefers certain species of things; for instance, she does not like cookie-cutter mansions, which, “as a species,” convey “aesthetic bankruptcy.”