The amateur writer of women’s erotica may be forgiven for thinking, as she pushes her manuscript upon Siren Publishing, Ellora’s Cave, and Carnal Desires, that she has finally entered a freewheeling realm of sexual exploration, an oasis of untrammeled erotic fantasy. She may continue under this impression as she scans the retail horizon, landing upon titles like Tall, Dark and Dominant, Male Android Companion, Two Men in Her Tub. But she is bound to be disabused when she stumbles upon the Guidelines for Submission, written always in that tone of world-weary prophylactic disappointment, and learns precisely what is not welcome. Ellora’s Cave, for example, does not want your pedophilia, incest, necrophilia, “rape as titillation,” “guns, knives or other weapons stuffed in various parts of the female anatomy,” or bestiality. Siren Publishing says no to “descriptions of bodily functions.” Carnal Desires bans all that plus “stories that portray murder as a sexual turn-on.”

These rules tend to hold across publishers; no one seems much interested in nurturing the next Marquis de Sade. And yet to read the collected Guidelines for Submission for erotic writing is to feel oneself pushing up against some darkly persistent erotic impulses. Though almost all of the authors of such erotica are women, every publisher feels the need to caution against conjoining weaponry with the female anatomy, and the drive to portray necrophilia in print is apparently strong enough that it need be everywhere banned. Then there are the exceptions, where good taste (whatever good taste might mean in the world of erotic e-publishing) pushes up against the reality of sales. The Wild Horse Press will bend the bestiality rule for werewolves, and will, should a story involve vampires and zombies, suspend the prohibition on necrophilia. Ellora’s Cave will accept bestiality in the case of shape-shifters, and, in fact, recently landed Tiger—a novel about a half-man, half-tiger who seduces a “small human female”—on the New York Times best-seller list.

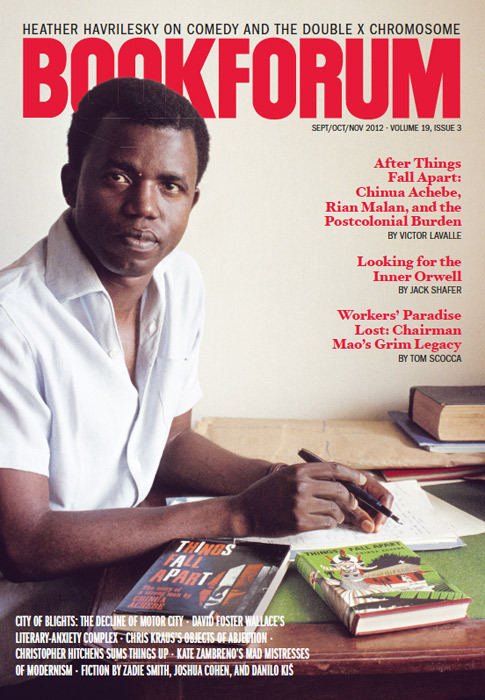

This is not a world many people noticed before the Fifty Shades trilogy (Vintage, $48) became the fastest-selling non–Harry Potter novels of all time, and in literary circles the genre exists mainly to be derided and demeaned or simply condescended to. In the latter category we find the descriptor naughty, the genre label “mommy porn” (which should, by all rights, refer to a fetish for pregnant women), and the relentless mocking of E. L. James’s prose, which I take to be no worse an artistic failure than the production values in the “Just Threesomes” five-pack currently selling very well at Adult Video Universe.

I don’t mean the comparison to be derisive, or to suggest that the books are trivial merely because they seek to produce a very specific response in the reader. When the French philosopher Georges Bataille described eroticism as “assenting to life up to the point of death,” he was talking about a moment of freedom from the prison of isolated existence, a moment in which an essentially discontinuous body might experience the kind of continuity with the universe we’ll all presumably find when our lives are over. In the erotic we bump up against the possibility of dissolution; there is a reason we call a certain kind of person “dissolute.”

The age of the anonymous reading machine, it turns out, is the age in which female protagonists seek a sustained sense of erotic rapture, and therein is the reason the editors at Ellora’s Cave and Carnal Desires find it necessary to publish a list of lines they will not cross. There is in the erotic that hard jolt of coming undone, the “elemental violence,” as Bataille put it, “which kindles every manifestation of eroticism.” Where we find the erotic we find anarchy, an unraveling, a falling apart, dissolution. We find, as in the work of Sade, Anaïs Nin, and the pseudonymous Pauline Réage, that a sexual frenzy spills readily into savagery.

It is enlightening to read Bataille not only beside popular erotica but also beside popular commentary on erotica, which tends to avoid talk of continuity, dissolution, or primal pain. One might expect, as I did, the thousands of essays written on the Fifty Shades trilogy to indict readers for reveling in retrograde fantasies of sexual submission. James’s protagonist, Anastasia Steele, cedes control, which is not a posture deemed appropriate for modern women, who are meant to be in control at work, in control at home; they are the tireless practical forces of civilization under which their joke-cracking husbands, if we take sitcom television to be instructive, may relax into an enviable adolescent fugue. If women are forever doomed to play the straight man, it’s because humor communes with the very chaos women are supposed to stave off. And yet, for the most part, the critical response to Fifty Shades of Grey has not been to deride the scenes of female submission to male dominance. The model Fifty Shades of Grey think piece, in fact, is a defense of the book against these killjoys, who are scarce if not imaginary, though these defenses do not extend to anarchy, or chaos, or ecstasy at all. In the Fifty Shades think piece, the book is a teaching tool, a means of instruction, Our Bodies, Ourselves with a stronger narrative drive.

Fifty Shades, we learn, is a force for “good” because it “gets women talking about sex.” It is good, we learn, because it “encourages a dialogue.” Fifty Shades, insists a panel of experts on The Dr. Oz Show, is an educative tool permitting healthy adult women to express their desires within the realm of companionate heterosexual marriage. “‘Fifty Shades of Grey’ is seen as improving women’s sexual health and wellness,” reads a headline in the Washington Post, and below we find a picture of smiling, manicured, fully clothed white women immersed in the book, smiling in what looks to be a drug-induced state of yogic calm.

The Washington Post never gets around to saying just what constitutes “sexual health,” but it presumably has something to do with conforming to current norms about communicating with one’s husband and nothing at all to do with chaos, risk, or elemental violence. Instead of finding yourself deranged or unraveled by tales of BDSM sex play, these anxious arbiters of cultural meaning come bearing the news that Fifty Shades will leave you even more tightly raveled—better adapted to your role as manager of a household, newly empowered to talk about “your needs” with a loving, committed partner over a glass of pinot grigio and some low-fat biscotti.

There is a scene in Fifty Shades in which college student Anastasia Steele allows a billionaire she doesn’t really know, and suspects is a sadist, to chain her to a wall in his “playroom.” It’s not behavior we associate with the ideals of self-preservation and delayed gratification, promoted by, say, Dr. Oz’s talk show. And to enjoy reading about this kind of thing is to spend hours in an imaginative space where chaos is not only possible but desirable. If talk of “wellness” is an attempt to remove the erotic from the realm of the savage and claim it for civilization, one wonders how far talk-show panelists are willing to go, how many sadistic horrors they can tolerate before they dip into their justificatory tool kits and come up empty. Is The 120 Days of Sodom, which involves the mutilation of children and the disemboweling of a pregnant woman, a “naughty” book? Does Story of O, which finds its protagonist tied up and branded with a hot iron, improve sexual wellness?

The whole of the first book in E. L. James’s trilogy might be seen as one woman’s struggle against norms of “sexual health.” Anastasia Steele is not under the impression that there is something health giving about being repeatedly flogged for disrespecting a dominant man—or that being someone’s sex slave “encourages a dialogue.” But she does get off on the proximity to dissolution, the flirtation with violence. And so, for many tedious pages I imagine most of us skim, she worries about what is acceptably normal, until she mercifully returns to the playroom.

Fifty Shades of Grey breaks none of the taboos listed on those Guidelines for Submission; it merely exists in a space where rules like “no weapons in dark places” become suddenly necessary. That the erotic moment can be cleaved so cleanly from chaos is a fantasy far more absurd than Anastasia Steele’s pursuit by “the richest, most elusive, most enigmatic bachelor in Washington State.” There are, it turns out, women who want to read stories in which protagonists get slapped around, have sex with tigers, and violate the nonvampire dead. There are women who have a space in their fantasy lives not colonized by a concern for their own longevity. That no one can bring themselves to say this, in a time when 20 percent of the adult fiction sold consists of dominance-and-submission fantasy play, is perhaps what you’d expect from a society so blushingly modest it could not collectively enjoy dirty stories for as long as books came with covers.