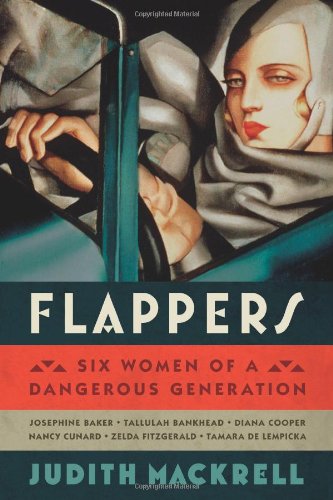

It is the unfortunate fate of many women of a certain period to be recalled not as individuals but as “flappers,” a word that seems, to modern chroniclers, a nearly irresistible invitation to a morality tale. A woman of the 1920s might refuse domesticity without consequence; a flapper, on the other hand, will burn brightly for a time before descending into the kind of callow, knowing narcissism that completes a particular narrative arc. We know many of these stories by heart: Zelda Fitzgerald fell into madness, and Tamara de Lempicka into obscurity. Tallulah Bankhead was a drunk, Josephine Baker never grew out of her childish need for adulation, and socialite-poet Nancy Cunard died alone after the friends whom she regularly abused abandoned her. Lady Diana Cooper passed away without a notable accomplishment. How miserable they were; how desperate to be loved; how transparently needy their cartwheels and fountain play.

“Much of what this flapper generation wanted to become,” writes Judith Mackrell in Flappers, her summation of the lives of the six women above, “was stalled or deflected by events of the thirties and forties.” F. Scott Fitzgerald described his mistress Sheilah Graham, whom he took when his wife was middle-aged and hospitalized, as “one of the few beautiful women of Zelda’s generation to have reached 1938 unscathed.”

It remains unclear whether any woman of any generation comes unscathed to middle age, but Fitzgerald’s sentimental scorn for the women of the Jazz Age seems particularly unsuited to Josephine Baker. Born to a mother who despised her, she responds to her grim childhood by dancing in front of St. Louis’s Booker T. Washington Theater until someone notices. That the woman who discovers her also wants sex does not pose an intractable problem, and by the age of nineteen Baker is arching and undulating in Paris (“some tall vital incomparably fluid nightmare,” according to the calculatedly breathless e. e. cummings), keeping house in a luxurious hotel room, surrounded by a small menagerie that includes a leashed pig.

Most of the women whom Mackrell portrays here indulge in the comfort of other women when convenient or career advancing. This is not to say that intimacy is wholly transactional or made light of; only that sex is allowed more than one meaning over the course of a lifetime. The painter Tamara de Lempicka tempts coy subjects with the possibility that she, too, would bare herself. Heiress Nancy Cunard, guilty under the weight of aristocratic privilege as men return maimed from the European front, distributes sexual favors as a charitable offering to the war effort. Adolescent thespian Tallulah Bankhead accepts the favors of older women as a safer alternative to those of men.

Mackrell is the dance critic for The Guardian, and while Baker is the only dancer among these six subjects, the others benefit no less for having been written up by someone sensitive to the way it feels to move through life. Zelda, standing atop a diving board, feels “her body as keen and sharp as a knife”; Zelda is quoted describing her own form as composed with “delightful precision, like the seeds of a pomegranate.” Women repeatedly revel in the way their skin stretches flat across their stomachs, the hard joy of a taut body on display. Shift dresses swing against their hips as they walk. Diana Cooper abandons the confinement of an aristocratic home, the expectation of a quiet marriage, to dance in bars bare-ankled and plunge into the cold Thames for night swims in the company of like-minded friends. Baker, one of the few women Mackrell mentions whose rebellion did not spring from the freedoms of privilege, transforms the “banana dance” she is asked to perform into something so unrecognizably anarchic that religious groups protest in cities across Europe.

The realization that such physical self-mastery cannot possibly last is often portrayed as a tragic epiphany: A young woman living in baffling ignorance of temporal duration wakes up one day, shocked, to find a single gray hair. To her credit, Mackrell does not indulge in this tendency. One imagines that the subject of Tamara de Lempicka’s The Model, said by Mackrell to be “fully absorbed in the drama of her own body,” knew better than most how bodies themselves are given to rebel. When Diana Cooper becomes pregnant, she responds by drinking quinine, and when that fails to resolve the problem, she resigns herself to what she calls a “grotesque” invasion of her form. Josephine Baker’s younger sister dies from a self-administered abortion involving carbolic acid; Zelda takes a pill to induce one and survives; Nancy Cunard finds freedom in an early hysterectomy.

To call Flappers a disjointed collection of potted biographies would not be entirely unfair. But Mackrell includes thoughtfully carnal descriptions throughout—eliciting the pleasure taken in a certain youthful, obedient body, enjoyed in the full knowledge of impending corporeal betrayal—from which something cohesive emerges.

The respective declines of the six dramatis personae are saved for the epilogue, which makes for a rather gruesome forty pages. There is the familiar Jazz Age trope of the stunt grown tiresome, the whimsy effortful. The glamorous Tamara de Lempicka follows her daughter from Paris to Houston, of all ungodly places, where she is scorned by society and her paintings fail to translate for the aesthetic elite of the Oil Belt. The cringe-worthy story of Zelda’s late attempts at professional ballet—“One could see the individual muscles stretch and pull. . . . It was really terrible,” a friend wrote of one performance—gets revived again here.

Is insisting upon embodiment a frivolous project? It seems a limited mind that could look upon the ecstasy of Josephine Baker and think, “That will not age well.” Zelda Fitzgerald declared an intention to “live as I liked . . . and die in my own way.” These goals are not obviously compatible. In this book’s best moments, tomorrow is an afterthought, worth little more than the last snap of a good line.

Kerry Howley is a writer in Houston. Her first book, Artists of Abandon, is forthcoming from Sarabande.