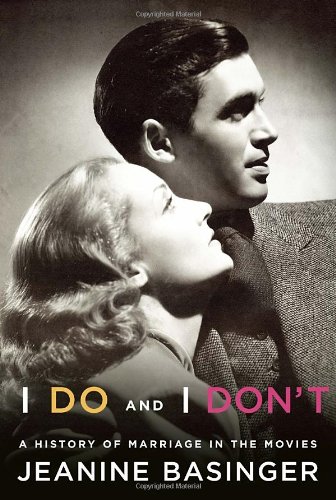

Of all the things one can portray in a movie, marriage is surely not the most titillating. It can’t possibly hold a candle to sex or violence—or some lurid combination of the two—and is an equally tough sell against horror, slapstick, sci-fi, romance, or the western. “Embrace happy marriage in real life,” director Frank Capra once remarked, “but keep away from it onscreen.” And yet there have been a great number of films, from the silent era until today, that have defied Capra’s warning and compellingly depicted one of the world’s most enduring institutions. (Capra himself offered a fiendish satire of “happy” marriage in his 1934 film It Happened One Night, and he’d revisit the subject many more times.) In I Do and I Don’t, film historian Jeanine Basinger persuasively argues that there is a long history of “marriage movies,” happy and unhappy, and that they’re often surprisingly entertaining.

Basinger divides her book into three parts, moving more or less chronologically from the early 1920s through the evolution of film and television in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Sandwiched between “The Silent Era” and “The Modern Era” is her most extensive section, “Defining the Marriage Movie in the Studio System,” a wide-ranging discussion of everyone from Nick and Nora Charles to Ricky and Lucy Ricardo, Tarzan and Jane to Laurel and Hardy (“Laurel and Hardy are a married couple,” she insists, “without the marriage”). There she develops a more systematic means of classification, laying out the problems (money, infidelity, in-laws and children, incompatibility, class, addiction, and murder) that shape most marriage movies in one way or another.

Many of these recurrent themes, each of which Basinger examines with humor, compassion, and a generally light touch, are indeed reflected in the very titles of marriage movies during the silent era. Among my favorites is the rather simple, if direct, The Marriage Cheat (1924). Or, equally piquant, Hot Water (1924), a feature starring the great silent comedian Harold Lloyd, which opens with the title card: “Married life is like dandruff—it falls heavily upon your shoulders—you get a lot of free advice about it—but up to date nothing has been found to cure it.”

Basinger suggests early on that one could almost write an entire book made up of nothing but quips about marriage extracted from the movies. And along the way, as she chronicles this vast and meandering history, she offers up a few zingers: In The Gorgeous Hussy (1936), Beulah Bondi enlightens Joan Crawford, telling her, “Marriage ain’t a party dress. You gotta wear it mornin’, noon, and night”; or, in a similarly salty spirit, Robert Benchley, in Janie Gets Married (1946), laments, “Marriage is being locked in a boxcar with a mad horse.” Showbiz pioneer and funnyman Eddie Cantor, who was married for nearly half a century, concocted his own apt definition: “Marriage is not a word. It’s a sentence.” Contrary to the garden-variety academic tome, I Do and I Don’t does not shy away from chattiness or from showing Basinger’s obvious pleasure in writing on movies she’s spent a good deal of time thinking about.

For Basinger, whose previous books include The Star Machine (2007) and A Woman’s View (1993), the films of Hollywood’s studio era, those lavish productions with stars and glamour, occupy a position of particular prominence. Her discussion is especially rich—brimming with acute observations and juicy bits of Hollywood lore—when dealing with such storied movie marriages as those of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers in The Story of Vernon and Irene Castle (1939) and The Barkleys of Broadway (1949); Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy in a number of A-list films of the 1940s; or Myrna Loy and William Powell in the acclaimed Thin Man movies. Basinger is similarly skilled at shedding light on the subtext lurking beneath a film’s glossy veneer (sly evasions of the Production Code, all manner of sexual innuendo, veiled allusions to contemporary issues).

By the time we get to the late ’60s and ’70s, the American movie landscape, as well as the larger cultural and political landscape, has shifted quite radically. As a stray line from Paul Mazursky’s free-love romp Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice (1969), uttered after the two couples travel to Vegas, has it: “First we’ll have an orgy, and then we’ll go see Tony Bennett.” Around this time, a number of films emerge that reprise some of the same old problems and pitch things to the new morality: Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf ? (1966), Divorce American Style (1967), and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967), among others. Basinger sketches these developments as she brings her discussion up to the present day. (The television series Friday Night Lights elicits a remarkably detailed and enthusiastic response: “It’s possible that there’s never been a more honest and natural marriage portrayed in film or television.”)

Ambitious and far-reaching as I Do and I Don’t is, Basinger never pretends it’s an exhaustive study—the book gives significantly less attention to foreign and art-house films than to Hollywood classics—or aims her work at a specialized audience. “In writing this book,” she asserts at the outset, “I am not analyzing sociological and cultural influences, discussing psychoanalytical theory or the differences between the male and the female gaze.” As she notes, “It’s a book for people who like movies and want to share a conversation about them.” And as any good book about the movies is apt to do, it inspires its readers to think about the films that are discussed in a fresh light.

Toward the end of I Do and I Don’t, Basinger quotes Dana Adam Shapiro, who, while at work on his film Monogamy (2010), interviewed a number of people who had been through a divorce. “All happy couples are the same, which is to say they are just boring,” Shapiro says, echoing Capra, and Tolstoy, and Annie Hall’s Alvy Singer. And yet Basinger’s book shows us how marriage, in all its myriad representations, is complicated. And isn’t that already a movie title?

Noah Isenberg’s new book, Edgar G. Ulmer: A Filmmaker at the Margins, is due out from University of California Press early next year.