My Struggle,the celebrated six-volume novel (or memoir) by the Norwegian writer Karl Ove Knausgaard, is—like nearly all grand endeavors—one of those books that shouldn’t work, but somehow does. He finished the project in 2009 in his adopted homeland, Sweden, where it was both a best seller and a lightning rod for literary debate. Three volumes have now been translated in the United States. The novel draws explicitly from Knausgaard’s own life—the narrator is named Karl Ove Knausgaard—and uses the real names of his wife, children, parents, and friends. Nearly four thousand pages, it is packed with the kind of quotidian detail that is hardly the stuff of high drama: some one hundred pages on the teenage narrator trying to buy beer; long descriptions of the mechanics of cleaning house and of a fight with his wife over the dishes. Knausgaard has said he wrote My Struggle fast and without much revision. He is not averse to cliché, his metaphors are mixed (“His fury struck like a wave, it washed through the rooms, lashed at me, lashed and lashed and lashed at me”); he often gets “needlessly” bogged down in exposition about who is walking where and exactly how his mother turns the key in the ignition and backs out of the driveway. Scenes that seem as if they are building to a crescendo, making the reader worry (will his mother get in an accident?), often just stop. On the face of it, Knausgaard seems to be making every mistake a novelist is taught not to make.

In lesser hands, these qualities would strike readers as boring and self-indulgent, but My Struggle is a revolutionary novel that is highly approachable, even thrilling to read. The book feels like a masterpiece—one of those genuinely surprising works that alters the tradition it inherited. As Knausgaard has said in an interview, when he began it, he was feeling ambivalent about fiction, a feeling that led him to want “to evoke all the things that are a part of our lives, but not of our stories—the washing up, the changing of diapers, the in-between-things—and make them glow.” Writing about banal things, it turns out, isn’t the same thing as being banal. But how can we explain this? Why are boring things—the stuff we find tedious in real life—not boring on the page? Knausgaard is not, like Warhol was in films such as Haircut, doing anything as radical as asking us to experience boredom for the sheer sake of it. Rather, he is trying to remind us how capacious the novel can be—and how much of life it has lately been in the habit of leaving out.

What makes My Struggle so hypnotizing—a word more than one reviewer has used to describe it—is in part the pleasurable surprise of seeing habits of mind (your apathy at a dinner party, or envy of a friend’s tracksuit, or momentary frustration with your partner) that normally go unrecorded put down in exhaustive detail. But it’s also the interplay between those lengthy, hyperrealistic scenes of everyday experience and what are in effect meditative essays. Reading My Struggle is a bit like walking around your apartment, working, talking to a friend, and worrying that global warming is irreversible, while noticing you need to clean the kitchen and thinking about that longer than you should. In Book Two, which closely deals with love and parenthood and art, there’s also a reservoir of suppressed rage at circumstance that further animates the tensions between flat subjectivity and profound insight.

My Struggle establishes its dual methods early: Book One opens with a beautiful set piece on the biological reality of death and mysterious memories of early childhood. But it quickly cuts back to the present, establishing that our narrator is a novelist in his late thirties, with three young children, who is also the son of a capricious and abusive drunkard, trying to be as unlike his father as he can be—he wants to be a good parent. He has been sitting in his office in Stockholm (it is 11:43 PM on the 27th of February of 2008, he informs us) writing the pages we have just been reading. He has recently left his first wife, moving from Norway to Stockholm, after falling in love with Linda, a depressive, magnetic young poet. As an artist he is radically ambitious; leaving a production of an Ibsen play, he thinks, “That was where I had to go, to the essence, to the inner core of human existence. If it took forty years, so be it, it took forty years.” “The longing for something else” is partly fulfilled by writing novels; but nothing, and no one, seems able to fully satisfy his yearnings—certainly love won’t.

Karl Ove and Linda have found themselves adrift in a sea of domesticity. Because Linda is taking a course at the Dramatiska Institutet, Karl Ove is a stay-at-home dad, feeding his kids, cleaning house, squeezing writing into the corners of his days, and wondering “why the hell” Linda hadn’t put their daughter’s shoes and coat away. “As a result I walked around Stockholm’s streets, modern and feminized, with a furious nineteenth-century man inside me.” He feels like a bad person because he stares longingly at the beautiful women he sees as he pushes the baby stroller around, and also spends quite a long time wondering why, exactly, women don’t look back at him. (Is it because he’s clearly taken? No, he decides, since women still looked at him when he and Linda walked around holding hands. It’s just “wrong” to be interested in the father of a young baby.) He grapples with his desire to be desired, his conflicting need for solitude, and his emotions surrounding the death of his father.

My Struggle is a very good book about twenty-first-century masculinity and its contradictions, and in this way, too, it feels very new: When have we read a domestic drama this detailed written by a man? My Struggle is a powerful portrait of the generation of fathers living out the still-fresh consequences of the feminist revolution, with its resulting daily conflict about who will change the nappies, take out the trash, and do the dishes. A far cry from stabbing your wife and running for mayor, or fishing in Cuba and hunting in Africa. The title My Struggle (in Norwegian: Min kamp) may have overtones of Hitler, but this struggle isn’t martial or epic, it’s domestic. In the broadest sense, Knausgaard is really writing about what it’s like to experience a sense of possibility slowly narrow into the actual lived days of a life gone by, like tissues from a box, heading toward one ultimate end. This lost possibility is a very contemporary problem, and the self-consciousness on view in My Struggle is a very contemporary self-consciousness, just as the one on view in Marcel Proust’s epic In Search of Lost Time, which Knausgaard has cited as an influence, was an early-twentieth-century self-consciousness.

Indeed, My Struggle chiefly concerns itself with what Jonathan Lethem, in a recent paean to Knausgaard, described as the presence of “selves bitterly incommensurate”—the coexistence of the iconoclastic artist, and the mundane wanting-to-be-liked self who calls home from his office, picks up groceries for dinner, and easily experiences humiliation. As Karl Ove reflects,

Everyday life, with its duties and routines, was something I endured, not a thing I enjoyed, nor something that was meaningful or that made me happy. This had nothing to do with a lack of desire to wash floors or change diapers but rather with something more fundamental: the life around me was not meaningful. I always longed to be away from it. So the life I led was not my own. I tried to make it mine, this was my struggle, because of course I wanted it, but I failed, the longing for something else undermined all my efforts.

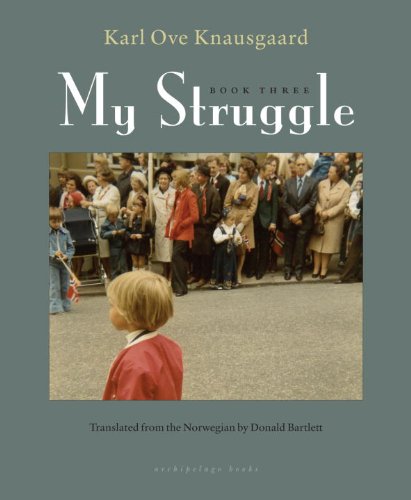

After Book Two—which moves forward in chronological time—it comes as something of a surprise that in Book Three, or Boyhood, Knausgaard circles back to his childhood in the late 1970s, on an “estate” on the island of Tromøya, in Norway. The novel searchingly covers some of the same ground unearthed in Book One (which revisits Knausgaard’s adolescence), including the legacy of his complicated father. In its preoccupation with the powerful aura children invest in objects, institutions, and books and music, Book Three is a kind of history of the mind as it is being shaped, capturing childhood’s intensities and confusions, as well as the amoral nastiness with which children can treat one another. It also shows us the power fiction can hold over a life: Reading functions as the one space indoors where Karl Ove feels free.

Though Boyhood lacks the adult tensions of Book Two (the best of the three books translated into English), it nonetheless contains an astonishing amount of everyday life, which is rendered in Knausgaard’s signature mix of nonchalance and fascination. Boyhood chronicles everything from a young Karl Ove’s first day at school to unsupervised exploratory hikes he and his friends take nearly every day in the forest. It includes childish disquisitions on comic books, porn, Elvis Presley, the mysteries of girls, the importance of music, and the pleasures of shitting in the open air, and watching insects slowly devour your shit, over days, weeks, months. Karl Ove’s self-questioning consciousness inflects every trivial moment: Reading about a boy who woke up one day in the Viking age, Knausgaard notes, by contrast, that “if I dreamed about anything, it was a pair of new, white trainers with the light blue Nike logo, like the ones Yngve had, or new light blue Levi jeans, or a light blue Catalina jacket.”

But the most captivating aspect of Boyhood is Karl Ove’s relationship with his father, a schoolteacher and amateur stamp collector. His father—unpredictable and harsh—is terrifying to the boy. “I lived one life indoors and another outdoors, as it had always been, and as I suppose it was for all children,” he writes. Yet it’s more the case for him and his older brother Yngve than it is for other children: Their father will not allow them to have friends over, and erupts in anger if they dare to run in the house. Knausgaard writes, “Whether he hit me or not made no difference, it was equally awful if he twisted my ear or squeezed my arm or dragged me somewhere to see what I had done, it wasn’t the pain I was afraid of, it was him, his voice, his face, his body, the fury it emitted. . . . The terror never let up, it was there for every single day of my childhood.” Book One showed us that Knausgaard’s father was frightening, but in Book Three, the many small, violent, unpredictable incidents accumulate to inspire a constant sense of sickening dread. By the time Knausgaard writes, quite matter-of-factly, that his mother—who made all the meals, cooked them treats, listened to them talk—saved him, “because if she hadn’t been there I would have grown up alone with Dad, and sooner or later I would have taken my life, one way or another,” it seems like sheer fact, not sensationalism.

The pervasive sense of menace helps answer the question of how Knausgaard manages to imbue ordinary incidents—a trip to the Fina station to buy candy, making a sandwich—with such powerful suspense. Reading Boyhood,one realizes that this peculiar suspense is mimetic of the anxiety an abused child feels. There is the sense that the ordinary trip to the gas station could morph into a terrible fight, in which his father might hit him; that losing a sock at swim class will lead to a violent confrontation; that walking past the study at the wrong moment could lead to a tongue-lashing. Growing up with an abusive father, one is never sure at what moment he might throw the bedroom door open and demand an accounting.

And in a sense that is exactly what this project is doing: offering an accounting. Knausgaard has said that he began My Struggle while trying to write about his father; he found that fictionalizing matters felt artificial, since he wanted to write about “my father.”So he began writing using real names, places, and dates. The discovery of fact is an artistic one; the pressure to blend genres, to move beyond conventions, is part of what makes this accounting feel so fresh. But because Knausgaard is a fiction writer by training (his other books include the award-winning 2004 novel A Time for Everything), he makes use of all the ambivalence and ambiguity that fiction channels, resisting the kind of summation or resolution that a confessional memoirist might have felt impelled toward. And ultimately, as he describes in Boyhood, it was in fiction that he found freedom from his father. Fiction may have its limitations in the modern world, where fact calls to us, but it is the space where you can reappropriate a story, a situation, to your own ends. This, too, is why so much everyday life is crammed into the book: Dull while lived, it shines on the page.

But what does it mean to make an accounting of a past you can’t fully remember? This elegiac dilemma is one of Knausgaard’s primary subjects—the difference between how we think about life and its actual moment-by-moment reality. He has said that one reason he wrote this novel in six parts was in order to show the way time changes our perspective: The terrifying tyrant becomes the shrunken Lear; the large, animated rooms of our childhood become small and plain. Likewise, Karl Ove’s father, so fearful here, evolves in Book One to a drunk who seems somewhat pathetic, diminished in reach. That book ends with a powerful image of the dead father:

Now I saw his lifeless state. And that there was no longer any difference between what once had been my father and the table he was lying on, or the floor on which the table stood, or the wall socket beneath the window, or the cable running to the lamp beside him. For humans are merely one form among many, which the world produces over and over again.

This passage points to a major difference between My Struggle and its great predecessor, In Search of Lost Time. In Proust’s novel, the character Marcel is able to find spiritual and aesthetic transport in the hawthorns on his walk, or in a piece of art. Karl Ove finds no such escape, and returns again and again to the plain realities of biological existence—in fact, the idea that we are all essentially things is one of his grand arguments. With its thickets of banalities, its preoccupation with our biological basis—a key scene here finds Karl Ove watching doctors perform open-heart surgery on TV—the book telegraphs a vision of lost spiritual dimensions, lost powers.

But even from within the confines of its banal subject matter and unadorned worldview, My Struggle still manages to gesture toward grandeur. Like Proust, Knausgaard believes that literature is, in some way, a form of real life. The opening of Book Three finds Karl Ove in a characteristically unsentimental mode: As he meditates on old photographs of himself, he notes, “Memory is not a reliable quantity in life.” He describes his childhood as a “ghettolike state of incompleteness” that he has built from “bits and pieces”—photographs and memories and objects. But by the book’s end, memory has become monumental, mythic: The recovered events these pages share with us are suddenly and unmistakably “real.” His family is leaving Tromøya. Karl Ove has lately been tormented by his classmates. (He slaps a girl in his class who tells him, “None of the girls like you.”) Leaving is a chance to start anew. As they drive away, he reflects, as the book concludes: “It struck me with a huge sense of relief that I would never be returning. . . . Little did I know then that every detail of this landscape, and every single person living in it, would forever be lodged in my memory with a ring as true as perfect pitch.”

A ring as true as perfect pitch? This final line verges on cliché, and one is tempted to read it as ironic—as it would be in the hands of a more self-consciously postmodern writer. But Knausgaard, for all his radicalism, can be rather sober in his aspirations. This is a comment, it would seem, about the ways stories persuade us of their reality. The act of remembering through writing is an act of recovery. Real life remains outside the text, waiting to be lived. But here, at least, the author can transform experience, turning the messy stuff of memory (“an unknown quantity”) into a note ringing clearly in the silence.

Meghan O’Rourke, a former fiction editor at the New Yorker, is the author of the poetry collections Once (2011) and Halflife (2007; both Norton) and the memoir The Long Goodbye (Riverhead, 2011).