In 2011 Ben Lerner’s first novel, Leaving the Atocha Station, was brought out by Coffee House Press, a Minneapolis independent, to wide and deserving if improbable praise. Improbable because of its provenance, but more so because its author, thirty-two at the time, was already a decorated poet, with three collections and a National Book Award nomination to his name. There are in recent memory American poets who write novels—from John Ashbery and James Schuyler to Forrest Gander and Joyelle McSweeney—but crossover success, measured in terms of attention paid by organs like the New Yorker and the New York Times, is rare. (As for the poetry of prominent novelists—e.g., John Updike and Joyce Carol Oates—perhaps the less said the better.) And improbably, too, one of the novel’s subjects was poetry and its failures.

The narrator of Leaving the Atocha Station, Adam Gordon, a twentysomething American on a fellowship in Madrid in 2004, worries that as a poet he may be a fraud, and that his experiences of art are inauthentic or insufficiently profound, something that could also be said of his two love affairs with Spanish women. Another poet we see in the novel is plainly bad, his work “an Esperanto of clichés: waves, heart, pain, moon, breasts, beach, emptiness, etc.; the delivery was so cloying the thought crossed my mind that his apparent earnestness might be parody. But then he read his second poem, ‘Distance’: mountains, sky, heart, pain, stars, breasts, river, emptiness, etc.” Much of the novel’s humor springs from Adam’s hostility to poetry, his general aesthetic ambivalence, and his uneasiness at being an emissary from “the United States of Bush.” It should be mentioned too that he spends a long stretch of the book taking more than the recommended dosage of his meds and high on hash.

The story of Adam’s overmedicated if highly intellectualized quarter-life crisis was loosed on American fiction at a time when writing’s reality quotient was the going debate, and it was in many ways a perfect specimen for those arguing (like David Shields in Reality Hunger) against conspicuous fictionality and unblurred lines. (Other specimens include Teju Cole’s Open City, Sheila Heti’s How Should a Person Be?, and the novels of Tao Lin.) Adam and Lerner share a résumé, and the book proceeds in a manner not unlike a diary, with a progress rather than a plot. Much of it is essayistic, a container for Lerner’s ideas about art and poetry (and bits of his poems), including thoughts he gives Adam from an essay of his own about Ashbery, whose “poems allow you to attend to your attention, to experience your experience.” Time is delineated in terms of “phases” of Adam’s “project”: Nominally the project is the research-based poem about the Spanish Civil War he’s been awarded the fellowship to write, but really it’s his life, and so it’s also the novel itself. The effect is the illusion of the boundary between life and art collapsing. Yet Leaving the Atocha Station didn’t leave you wondering whether what happened to Adam happened to Lerner. Who was Lerner in 2011 but some precocious poet with eyebrows that, like Adam’s, look sort of like Jack Nicholson’s?

But now he’s a successful young novelist, and the fauna of the literary ecosystem, not to say book reviewers, love nothing better than the schadenfreude that attends the spectacle of a sophomore slump. Perhaps that’s especially the case when the novelist has received a swell book deal, and has moved, in the manner of a sellout, to a corporate publisher. This is one scenario dramatized in Lerner’s new novel, 10:04. Its narrator has in common with Lerner a first name, residence in Brooklyn, a teaching job at Brooklyn College. The Ben of 10:04 has written a novel that, though never named, sounds like Leaving the Atocha Station. When Ben goes on dates, women seem to be checking to see if they’re sitting across from Adam Gordon. “You sound like your novel,” somebody says. Having a slight panic attack, Ben worries that he’s “become the unreliable narrator of my first novel.” Ben also purports to be the author of 10:04, the book he’s now narrating, for which he’s earned $270,000 after taxes and the agent’s fee. Will it have an accessible, schematic plot and plenty of character development? Or will he “write a novel that dissolves into a poem about how the small-scale transformations of the erotic must be harnessed by the political,” i.e., a “novel everyone would thrash”?

How seriously should we take this novel-about-my-book-deal metafiction? Ben is the sort of person intellectually curious about the systems of commerce but not much interested in (or capable of) writing commercial fiction. He conceives of and scraps a plot involving forged letters from dead poets that he intends to sell to a university archive: the great epistolary-poetic fabrication thriller of 2014! But we know that’s not the sort of novel we’re reading. 10:04 is instead another progress, and the metafiction acts as a binding agent. The narrative stretches from the summer of 2011, marked by the threat of Tropical Storm Irene (a short time after the release of Leaving the Atocha Station), to the autumn of 2012 and the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy. Is Ben the narrator Lerner the author? He’s fairly frank about his method, which he’s borrowed from his poetic practice: “Part of what I loved about poetry was how the distinction between fiction and nonfiction didn’t obtain, how the correspondence between text and world was less important than the intensities of the poem itself, what possibilities of feeling were opened up in the present tense of reading.”

So 10:04 is a novel of intensities, an unfolding present. Some of this present is personal. At the start, Ben is diagnosed with “an entirely asymptomatic and potentially aneurysmal dilation of my aortic root” that could turn the artery into “a whipping hose spraying blood into my blood.” He’s also trying to impregnate his best friend Alex by artificial insemination (“fucking you would be bizarre,” she tells him). And he’s casually dating a conceptual painter named Alena with a taste for autoerotic asphyxiation. Other strands of the novel put Ben into contact with aspects of the city. He tutors an eight-year-old boy named Roberto, a well-drawn character but also a surrogate-son figure and an emissary from the immigrant class—Ben is constantly aware of being served by people who speak Spanish. Politics enters in the form of an Occupy protester who uses Ben’s shower and eats a meal he cooks, and an Adderall-addled student fixated on environmental apocalypse. Ben sits at the bed of a hospitalized mentor, who represents a connection with a vanishing avant-garde. He publishes a story in the New Yorker, fretting over whether he’ll let its editors “standardize” his work. After he signs his book deal, there’s an interlude in Marfa, Texas, where he sees the specter of Robert Creeley. At a party just before he sees the ghost, he snorts what he thinks is cocaine:

I saw myself from the outside, in the third person, in a separate window, laughing in slow motion—but then, having done such a stimulant, why was I outside myself; why was time slowing? Before I knew it, I was trying hard to hold on to that question, felt it was the last link between me and my body, but soon the question didn’t belong to me, was just another thing there in the courtyard from which my consciousness was turning away. Then I was a relation between the heaters, the sky, and the blue gleam of the pool, and then I was gone, wasn’t anything at all, the darkest sky in North America. The last vestige of my personality was my terror at my personality’s dissolution, so I clung to it desperately, climbed it like a rope ladder back into my body. Once there, I told my arm to move the cigarette to my lips, watched it do so, but had no sense of the arm or lips as mine, had no proprioception. . . . Only after the young woman in the bathing suit said, “K—ketamine—mainly, I thought you knew,” did I hear myself ask, “What the fuck was that?”

“Proprioception” is the sort of hyper-specific Latinate diction Lerner takes great pleasure in—Ben’s frequent visits to the hospital afford plenty of opportunities for its deployment—but his tone never veers too far away from “What the fuck?” The way he writes about drug experience isn’t much different from the way he writes about art—he’s after all most interested in experiences of art, profound or otherwise—and 10:04 contains many discussions of artworks, including Jules Bastien-Lepage’s Joan of Arc, The Third Man, Back to the Future, the poetry of William Bronk, Christian Marclay’s The Clock, Walt Whitman’s Specimen Days, the rigorously inoffensive pictures on the walls of doctors’ offices, and Alena’s paintings. Alena has also assembled a collection of artworks in the possession of an insurance company, so damaged that they no longer count as artworks on the market—“zero-value” art. Ben’s discussion of her “Institute for Totaled Art” is fictionalized from Lerner’s discussion of Elka Krajewska’s Salvage Art Institute in an essay he wrote for Harper’s, and Lerner’s use of the novel as a receptacle for his ideas is also a way of showing us, with gentle pats of semi-ironic didacticism, how to read (and how he wrote) 10:04. The title comes from the moment in Back to the Future (Ben’s favorite movie) when lightning strikes the courthouse clock tower, allowing Michael J. Fox’s Marty McFly to zoom back to the ’80s in his tricked-out DeLorean. That scene is part of Marclay’s collage of time shots in The Clock, about which Ben says: “It was a greater challenge for me to resist the will to integration than to combine the various scenes into a coherent and compelling fiction, in part due to Marclay’s use of repetition.”

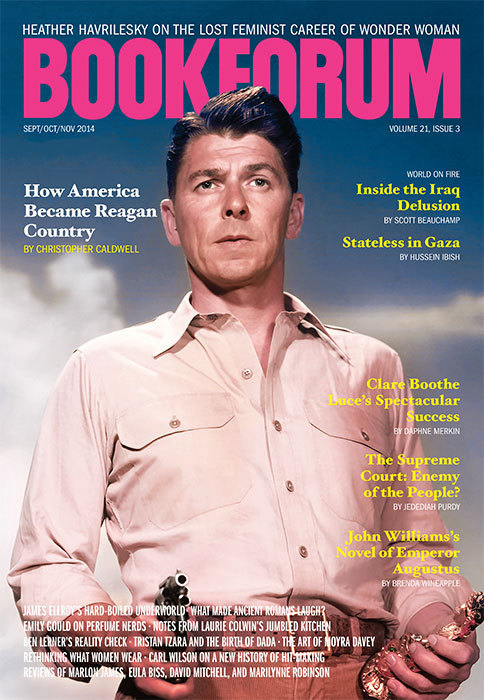

Of course, he might as well be talking about 10:04. The novel as thought receptacle isn’t a mode without risks: There he goes again, banging on about his trip to the Met. But it’s the integration of the criticism and the fiction—of the thinking and the living—that’s part of the unique achievement of 10:04. Lerner invites a comparison to the work of J. M. Coetzee, another novelist with a tendency to blur himself and his protagonists and to use the novel as a Trojan horse for his ideas. Twice in 10:04 we encounter a “distinguished South African writer” with a salt-and-pepper beard (I doubt it’s Breyten Breytenbach), the second time on a panel at Columbia after Ben delivers a speech on how the Challenger disaster inspired him to become a poet (another instance of Lerner using collage and appropriation and dispensing clues about how to read his novels; Ben wouldn’t have become a poet, it turns out, without the example of Reagan speechwriter Peggy Noonan). The panelists issue platitudinous imperatives about writing: “Think of the novel not as your opportunity to get rich or famous but to wrestle, in your own way, with the titans of the form.” And at dinner afterward the suspiciously Coetzee-like titan is mocked by Ben for his “logorrhea”: “It was clear to everyone at the table who had any experience with men and alcohol—especially men who had won international literary prizes—that he was not going to stop talking at any point in the meal. . . . [The] evening was doomed.” What a disgrace!

There’s a delicious arrogance to all of this, offset by Ben’s often crippling anxiety, his worries about his abnormal sperm, his suspicion that Alex wants him to father her child because he’d be a harmless absentee father rather than an all-too-present bad dad. The most grandiose declaration of Ben’s intentions comes on the second page, when he describes the way he should have described 10:04 to his agent on signing the deal: “‘I’ll project myself into several futures simultaneously,’ I should have said, ‘a minor tremor in my hand; I’ll work my way from irony to sincerity in the sinking city, a would-be Whitman of the vulnerable grid.’” Whitmanesque isn’t the way you’d describe Leaving the Atocha Station or its narrator. One possible flaw of that book and of its narrator was that he couldn’t get out of his own head: The force of his persona was achieved at the expense of the other characters, particularly Adam’s two girlfriends, Isabel and Teresa, who to some critics seemed interchangeable. You could take this as a defect in the fiction—a fatal sign of narcissism—or as one of its features: a persona constantly running up against its own limits, limits that give the book its shape. (I tend toward the latter view.) Those limits were of course the limits of a twenty-five-year-old mind, in which every romantic encounter is a matter of pure potentiality, and even more so for an expatriate like Adam Gordon, who knows he’ll be going home and that any emotions have an expiration date.

Thirtysomethings in Brooklyn tend to go at things with a colder realism. Alex’s pragmatic enlistment of Ben in her reproductive plans complicates their friendship and lends the book a minor undercurrent of dramatic tension: One night he (tenderly) gropes her while she’s sleeping (albeit with plausible deniability); another night he makes a drunken pass at her. Alena meanwhile has a “capacity to establish insuperable distances no matter our physical proximity.” These are the two models of male-female relations in 10:04: old friends driven to have a child together by necessity, and casual text-message-driven copulating fueled by a vague intellectual connection. Walking away from the fertility clinic, Ben imagines a conversation he might have with his future daughter:

“So your dad watched a video of young women whose families hailed from the world’s most populous continent get sodomized for money and emptied his sperm into a cup he paid a bunch of people to wash and shoot into your mom through a tube.”

“Wasn’t the tube cold?” [. . .]

“You’d have to ask her.” [. . .]

“How are you going to pay for all this?” she asked me.

“On the strength of my New Yorker story.” [. . .]

“Is that why you’ve exchanged a modernist valorization of difficulty as a mode of resistance to the market for the fantasy of coeval readership?”

“Art has to offer something other than stylized despair.”

“Are you projecting your artistic ambition onto me?”

“So what if I am?”

“Why didn’t Mom just adopt?”

The conversation, which conveys 10:04’s persistent and satisfying humor, comes halfway through Ben’s march from irony to sincerity. By the novel’s end, he’s on the bridge, looking over the whole city, quoting Whitman, the journey complete and the boast fulfilled. This is a beautiful and original novel. Lerner’s book is marked by many reminders of death and dying: Ben’s faulty aorta, the ecological turmoil suggested by two superstorms. But 10:04’s prime theme is regeneration, biological and artistic, and it signals a new direction in American fiction, perhaps a fertile one.

Christian Lorentzen is an editor at the London Review of Books.