These days, comic-book enthusiasts are often portrayed as somber scholars, and feminists get caricatured as obsessive eccentrics—so it’s natural to wonder when, exactly, the world went topsy-turvy. A mere glance at photos of suffragettes marching proudly in the streets in 1917 can incite a feeling of liberation vertigo: Where did the last century go? Women’s rights entered a swirling comics-style time tunnel and emerged looking more like a fanatical hobby. Meanwhile, creating superheroes was transformed from a down-market, and definitely obsessive, side project into a handsomely rewarded higher calling.

The absurd degree to which gender typecasting can render a field either honorable or execrable, elevated or debased, turns out to be just one shade on the color wheel of disappointment that attends the history of our pop-cult obsessions and political attitudes. We’re unable to isolate the precise moment when the battle for respect and freedom for women ground to a halt—just as we cannot pinpoint the onset of a new, retrograde consensus in the gender struggle. Instead, we seem condemned to witness, as though in the throes of a nightmare, a corrosive reactionary attitude supplanting former heroic breakthroughs—an apparently endless cultural clown show of incremental advancement followed by punishing regression.

Year after year, decade after decade, as fictional superheroes triumph on the big screen, our real-life feminist crusaders, if they are remembered at all, are eventually recast as vainglorious neurotics, ranting donkeys, and/or aggressive bag ladies. Somehow, the true superheroines, who spent decades valiantly fighting for low-cost contraception, equal pay, and affordable child care, invite trivialization and contempt. Mostly, we need to know that Gloria Steinem, at age eighty, colored her hair. We need to remember that Betty Friedan was “famously abrasive,” “thin-skinned and imperious,” and that Adrienne Rich was fueled by “a towering rage.” That’s not an assessment Rich would have contradicted, but she might have been amused by how consistently female passion elicits outrage, while male passion elicits awe.

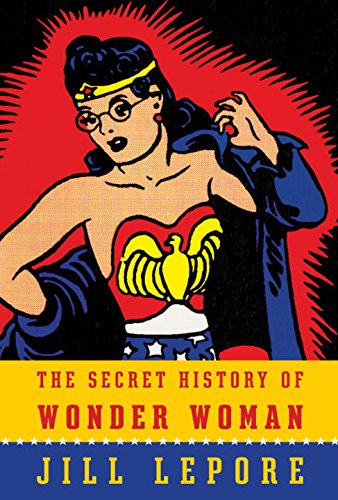

To be fair, it takes a special kind of confidence and courage of conviction to swim against the tide. When the world is topsy-turvy, sometimes only the arrogant, the eccentric, and the arrogant eccentrics feel comfortable saying so. And if there’s one dominant melody line to Jill Lepore’s The Secret History of Wonder Woman (New York: Knopf, $30), it’s the “Arrogant Eccentric Meets World” theme—an upbeat, whimsical ditty that takes a dark, minor-chord shift toward the end. The story of William Moulton Marston, the Harvard-trained psychologist, inventor of the first lie-detector test, and creator of Wonder Woman for DC Comics, is at once inspiring and disheartening. His unlikely career shows us (among other things) that the qualities that make it possible to innovate—swagger, cleverness, tenacity—are the same ones that can render a person hopelessly out of sync with the reigning strictures of the times.

Marston was an outspoken supporter of women’s rights from his college years forward; indeed, he firmly believed in, and proselytized for, the superiority of women. Paradise Island, Wonder Woman’s homeland, foreshadowed those Greek-goddess planets on Star Trek, where women in togas lamented the foolishness and self-destructive aggression of men. Martson designed Wonder Woman, he said, to be “psychological propaganda for the new type of woman who should rule the world.” Wonder Woman, introduced in 1941, was strong but fair. She hated guns but loved America. And she departed Paradise Island to “fight fascism with feminism.”

Marston’s Wonder Woman might have worn a bustier, hot pants, and “kinky boots” (as Lepore puts it)—not a bad way to ensure that you’re wildly popular in the ’40s—but her actions were undeniably feminist. In one episode, she organizes a big demonstration against profiteering industrialists, inspiring poor mothers and children alike to march in protest against the “International Milk Company.” In another episode, she ties up a department-store owner with her golden lasso and challenges her unfair labor practices.

Wonder Woman stood firmly against societal ills, from low wages to pointless aggression to bossy husbands who expect to be served by their docile wives. (For his part, Marston was married to an educated, confident woman, Sadie Elizabeth Holloway, and as to the question of domestic docility . . . well, read on.) An early press release explained that Wonder Woman was conceived to “set up a standard among children and young people of strong, free, courageous womanhood; and to combat the idea that women are inferior to men, and to inspire girls to self-confidence and achievement in athletics, occupations and professions monopolized by men.”

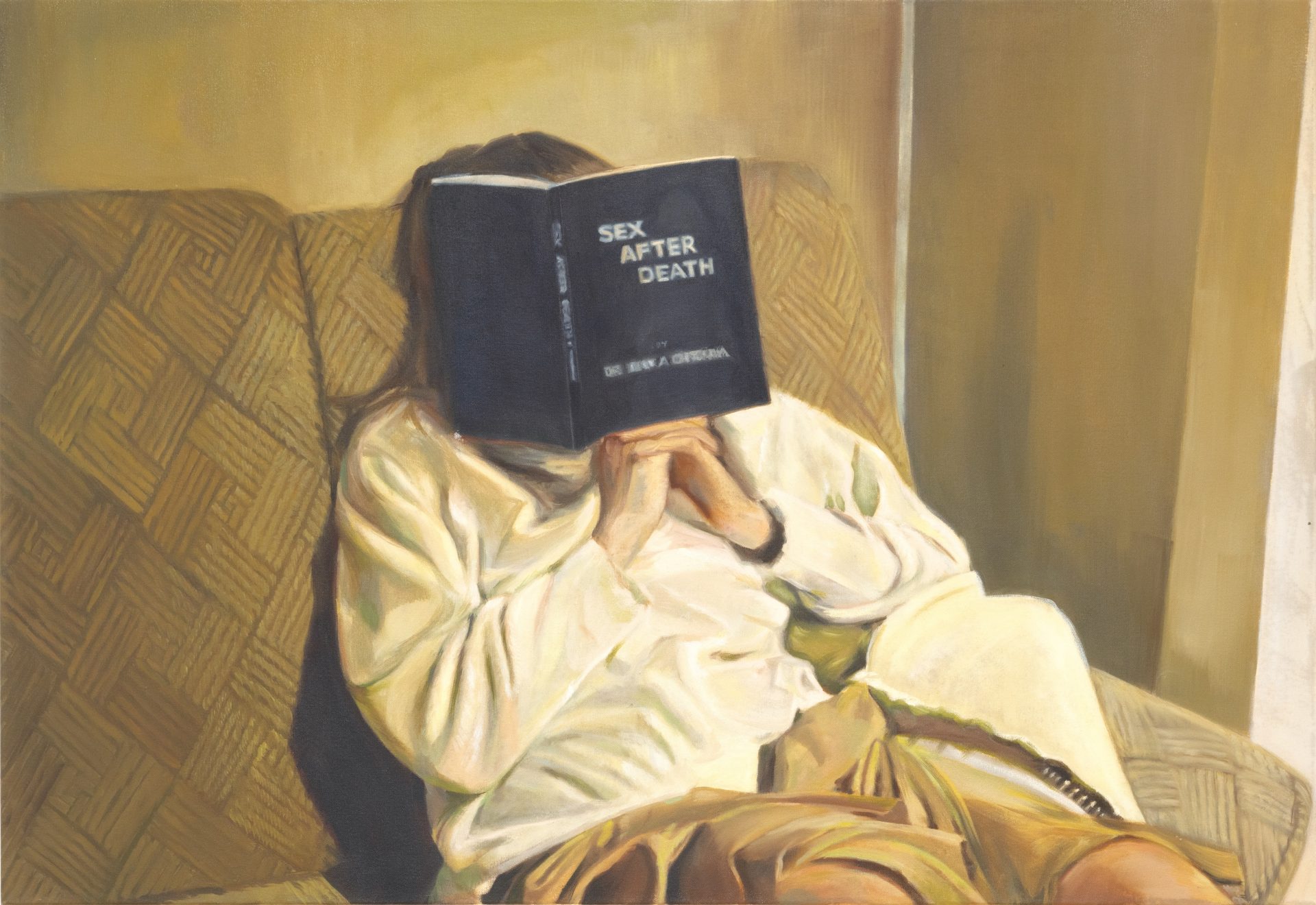

But just as the mind reels at how progressive and bold Marston was, we spin the disappointment wheel yet again. Because soon, people naturally began to ask, Why does Wonder Woman, in her kinky boots, end up tied up or chained in every story? According to Marston, Wonder Woman—like all women—loved to be tied up. “The secret of woman’s allure,” Marston reportedly told DC Comics editor Charles Gaines, was that “women enjoy submission—being bound.” It’s not sadism, Marston insisted, because the comic-book characters never suffer “or even feel embarrassed.” Marston called this rather creepy leitmotif “the one truly great contribution” of the Wonder Woman comic strip. “The only hope for peace is to teach people who are full of pep and unbound force to enjoy being bound—enjoy submission to kind authority, wise authority, not merely tolerate such submission. Wars will only cease when humans enjoy being bound.”

Shackles, the true key to humankind’s liberation? This is the kind of conviction that one might be able to shrug off as quirky or harmless, but, alas, the plot thickens. As a Tufts professor, Marston had discovered an undergraduate student named Olive Byrne, whose pep and unbound force impressed him enough that he involved her in his studies into whether women find being bound pleasant or titillating. (Guess what? They do!)

Soon after, Marston brought Byrne home to his wife, so that her pep and unbound force might be put to good use in a more domestic setting. According to Lepore, Marston told Holloway she had a choice. “Either Olive Byrne could live with them or he would leave her.” Holloway consented, Byrne moved in, and five children arrived over the years, three by Holloway and two by Byrne. (Cue clown-show theme song.)

This is the point in our story where the partially liberated woman, fueled by her plucky and mischievous feminist proclivities, sighs deeply. Because even those skeptical of the dominant heteronormative paradigm can’t help but question a man with two wives—one (Holloway) toiling in the workplace to supplement his stalled career, and the other (Byrne) toiling at home to raise all of his children. If HBO’s Big Love couldn’t warm us up to the concept of a contented gaggle of sister wives, tying little shoes and baking bread as a happy village, one bondage-loving iconoclast with delusions of grandeur isn’t likely to change our minds, either. And while Lepore’s book is packed with the sorts of painstakingly researched quotes and facts and maybes and perhapses you’d expect from a respected history professor with a number of similarly well-researched books under her belt, the very central issue of whether Marston and his family were truly liberated by their eccentric choices isn’t one that she dares to examine too closely.

We are left to interpret the facts as we will. Marston’s wives seem to dote on him. Marston’s children don’t believe that bondage was part of the sexual routine in their happy (albeit unusual) household. Byrne, the daughter of hunger-striking feminist Ethel Byrne and niece of contraceptive-rights crusader Margaret Sanger, gave no indication that she felt demeaned by her role. Indeed, she wrote repeated, rapt profiles of Marston for Family Circle magazine, in which she “visits” Marston’s house (i.e., her own house), marvels at the well-behaved children (whom she is actually raising), and is charmed by the man of the house (her life partner).

Yes, this is truly a household of bullshitters. Even so, although only a few trusted friends knew of Marston’s strange domestic arrangement, those who visited the house spoke in glowing terms of the joy and fun they witnessed there. Holloway and Byrne must have agreed; they lived together for more than forty years after Marston’s death from cancer in 1947, at the age of fifty-three.

But where does that leave the rest of us? With a Wonder Woman who, in the wake of Marston’s death, lost her strong feelings about women’s liberation (and her interest in bondage) and later took the televisual shape of Lynda Carter, a beauty-pageant winner, who inspired lots of little girls to spin in circles in the ’70s but not much else. “One tragedy of feminism in the twentieth century is the way its history seemed to be forever disappearing,” writes Lepore in the book’s final chapter. If The Secret History of Wonder Woman offers us anything beyond good old American marital melodrama, it’s an extreme close-up of that disappearing history, from Olive Byrne’s courageous matriarchs to the present moment, in which proclaiming your fanciness while shaking your booty is often mistaken for empowerment. The endlessly repeating reel of clown-show fisticuffs in between—the battle is rejoined, the battle is halted, progress is somehow undone, the familiar regressive attitude sets in—might pair nicely with a doleful sound track, to mourn the loss of our shared history. But once we’re done playing it all back (in high definition, in slo-mo), we need a new superheroine to prevent us from sleepwalking through the next one hundred years. All hail Remember Woman!

Heather Havrilesky is the author of the memoir Disaster Preparedness (Riverhead, 2010).