Barbara Comyns was born in 1909, the fourth of six children, to a very eccentric mother and father who lived in a large house in a small English town called Bidford-on-Avon. On a map of England, this town appears to be at the exact center, about two hours outside London, and if you look more closely—say, via Google Earth—you get an impression of almost impossible quaintness, a village of Tudor cottages and ancient stone bridges and charming pubs alongside a peaceful tree-lined river. Barbara Comyns’s first and third novels, Sisters by a River (1947) and Who Was Changed and Who Was Dead (1954), take place there. They are not quaint. It’s hard to pinpoint what makes them so disturbing. They are full of horror, but they’re not quite gothic. They’re about family life, but they aren’t cozy or domestic. On the second page of Who Was Changed, in the middle of a long description of the wreckage wrought by one of the river’s periodic escapes from its banks, there’s this passage about some drowning chickens: “They sat on their eggs in a black broody dream until they were covered in water. They squarked a little; but that was all.”

Motherhood—indeed, parenthood—as a black broody dream is one of Comyns’s themes, but her writing is so often antic and funny, full of odd little turns of phrase and words (“squarked”), that it takes the reader some time to notice how awful her portraits of family life really are. Her own mother, who is the basis for mother characters in those two early books, bore six children in rapid succession, and the trauma of her final labor left her deaf. Her father was a failed industrialist who alternated between drunkenly tyrannizing and ignoring his family. Comyns and her siblings were largely left to their own devices, which was both fun and scary; they had a good time, but also had frequent brushes with death. Comyns was educated by a series of governesses, none of whom stayed with the family long, and she later claimed not to have read any books until she escaped to London to attend art school. This incredible claim seems to be borne out by the books she wrote: Her sensibility seems to have developed without the guidance of literary forebears, and the results are original, strange, and discordant. Her tone is forever at odds with her subject matter.

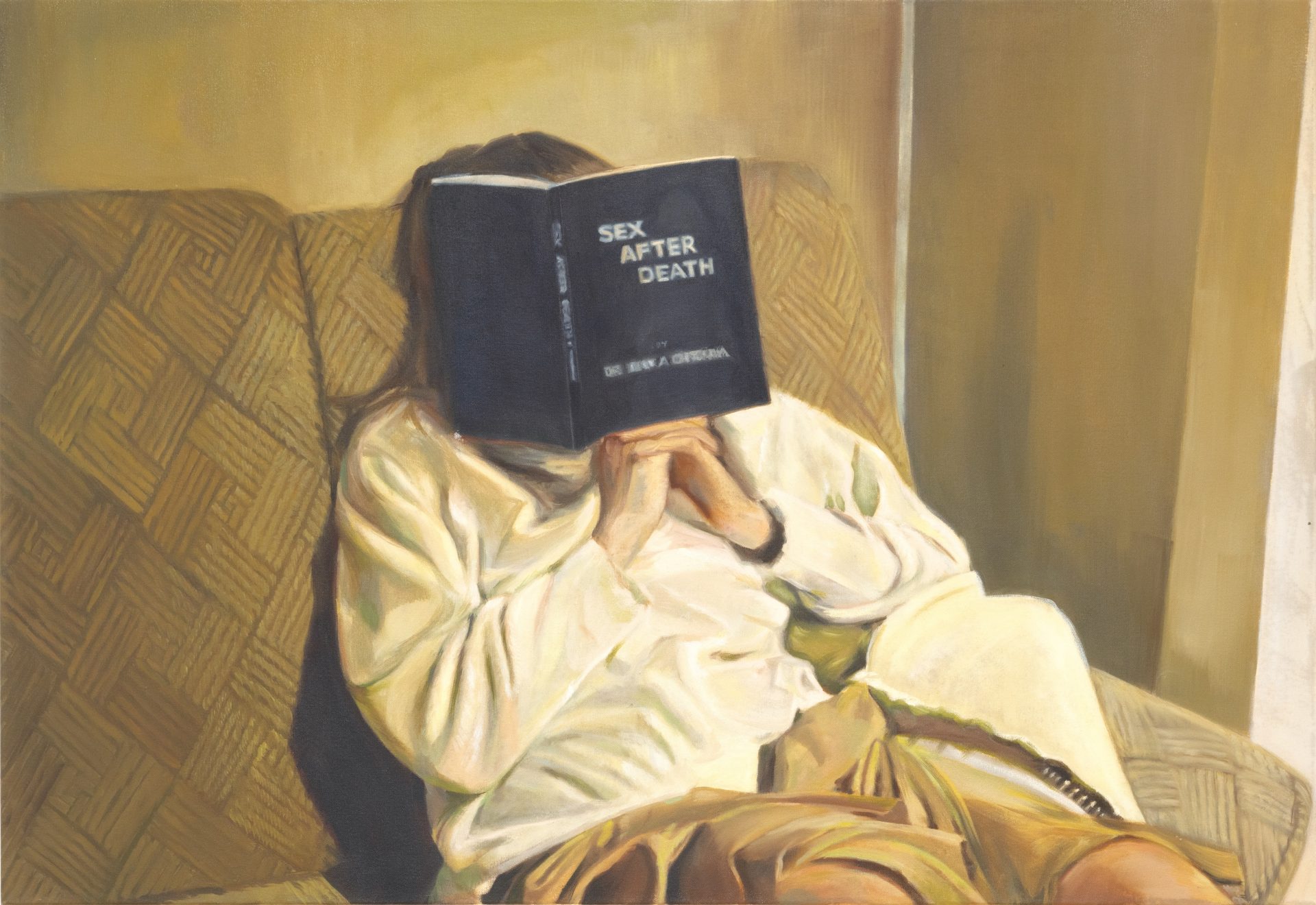

In Comyns’s second novel, Our Spoons Came from Woolworths (1950), the first-person narrator is no longer a child but a childlike adult, no longer subject to the whims of demented parents but soon to be a very inadequately prepared parent herself. Though it is not quite a memoir, my edition contains this note on the copyright page: “The only things that are true in this story are the wedding and chapters 10, 11 and 12 and the poverty.”

The story begins all madcap and charming, describing the narrator Sophia’s marriage to Charles, a painter from a snobby family who somehow has no money; her meager salary from a commercial-illustration studio supports them both. Soon after their wedding, to her husband’s surprise and anger, she finds herself pregnant. “I said, ‘I don’t want to be a beastly Mummy either; I shall run away.’ Then I remembered if I ran away the baby would come with me wherever I went. It was a most suffocating feeling and I started to cry.” Nonfictional chapters 10, 11, and 12 describe going into labor and then giving birth circa 1930 in a London public hospital. Comyns’s gift for understatement serves the nightmarish quality of these scenes well. When Sophia’s water breaks, she thinks she has become so fat she has burst. Her husband is annoyed and tells her she is always imagining things. At the hospital, she is bullied, shaved, given castor oil then shamed for being sick, drugged, restrained, and never told what is happening to her or why. “They told me to be quiet. I longed to cry out, but knew they would be angry, so bit my hands. There are still the scars on them now.”

Though many of the scenes of early motherhood are tender and loving, Sophia’s second baby meets with a grim fate after her useless husband abandons the family. The only thing that relieves the book’s almost unbearable sadness is that the narrator is recalling it from a distance; “I told Helen my story and she went home and cried” is its first sentence. The real circumstances of the book’s composition echo this structure: According to Comyns, she became a novelist when she began writing down the stories of her youth that she told her own children when they were living in the countryside outside London during the Blitz. This explains so much of what gives her novels their mesmerizing power; they have the quality of something recounted around a fire, after the danger has passed, to both edify and terrify an audience. “You are safe at home,” these stories all seem to be saying, “except when home is the most terrible and dangerous place of all.”

Emily Gould’s most recent book is the novel Friendship (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2014).