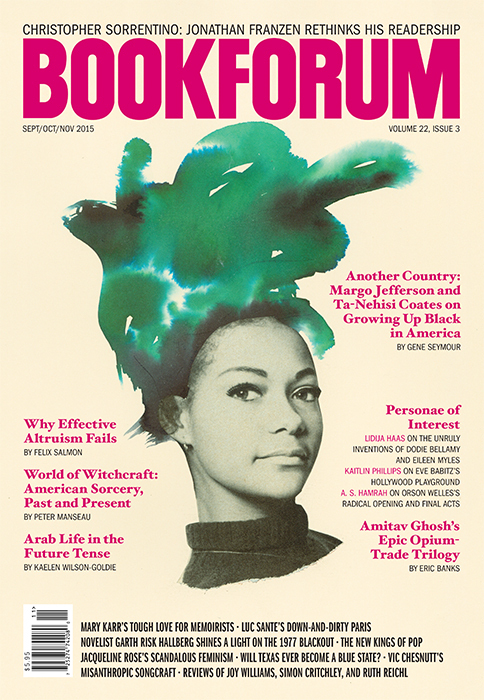

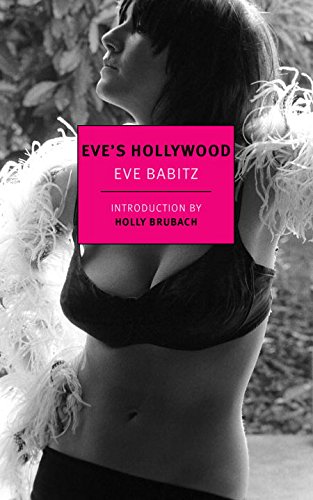

A golden girl in the Golden State, Eve Babitz, the daughter of a well-regarded Hollywood studio musician and goddaughter to Stravinsky, was seen—in all the places you go to be seen in Los Angeles—before she was heard. Her first book, the glossy, memoiristic essay collection Eve’s Hollywood (1972; reissued by NYRB Classics, $18), published when she was twenty-eight, remains Babitz’s most-read work, and the hardcover edition has long been a coveted coffee-table prop. Its jacket boasts an Annie Leibovitz photograph of a busty Babitz lounging in a black bikini and feather boa, proof that the silky avatar of this “confessional L.A. novel” is none other than the author. There were already two famous photographs of Babitz. Ed Ruscha put her snapshot in Five 1965 Girlfriends (he married one of the other four). Two years before that, Julian Wasser had shot her playing chess with a stately, aging Duchamp. The surrealist wears a suit; the ingenue is nude. The story goes that, as planned, her married boyfriend, the artist Walter Hopps, heard about it and stopped ignoring her calls. She was twenty years old. (A 2014 Vanity Fair profile helped revive the Babitz mythos: “Said Earl McGrath, former president of Rolling Stones Records, ‘In every young man’s life there is an Eve Babitz. It’s usually Eve Babitz.’”)

Babitz takes to the page lightly, slipping sharp observations into roving, conversational essays and perfecting a kind of glamorous shrug: “Mainly I withdrew from ‘hippies’ because they didn’t have any money. . . . None of them seemed to have an ounce of worldliness.” She rattles off what she learned at Hollywood High and the Hollywood Branch Library; drinks at the Luau and the Troubadour; drives to the Watts Towers and on Sunset (“Most people would take the freeway, but that’s a little too coldhearted”); spends a year in New York City with a cat “given to me one day by a poet who’d gotten the mother cat from Frank O’Hara.”

One piece begins with Janis Joplin overdosing on a Sunday at the Landmark Motel, and with press coverage that “clung pretty much to the theory, ‘What else is a Janis Joplin going to do on a Sunday afternoon alone in L.A.?’” Babitz has an answer: “She could have gone to Olvera Street and gotten taquitos.” Over the next ten pages, she takes us on a drive through LA’s history, shows us the guys who make the taquitos and exactly how they do it, and points out the Mexican mothers in the neighborhood who dress their daughters for Mass so they look like “floated camellias, angels.” Babitz doesn’t have to come out and say that there’s more to LA than klieg lights and malaise (“Taquitos are much better than heroin, it’s just that no one knows about them”). With the oiled reflexes of a local used to preempting outsiders’ asinine assumptions about California, she lays out how much else there is to see once you escape your depressing room at the Landmark. Taking the convenient coldhearted freeway to get a taquito, she writes, is “for if you don’t want to know about anything, you just want to get there. Maybe you should stay in your motel and shoot up and get there once and for all.”

All her aperçus and anecdotes are held together by a mood, a tone, the persona she deftly carved out for herself: a muse who is amusing. “If what you desire relies strongly on being all of a piece, you might as well face it or you won’t get what you desire.” That’s Babitz on buying taquitos again, but it could just as well be about herself: She made sure she was all of a piece, in pictures and on the page. And that ensured that she would get what she desired: “What I wanted, although at the time I didn’t understand what the thing was because no one ever tells you anything until you already know it, was everything.”

Her work is often criticized for upholding nothing but the pleasure principle. “It takes a certain kind of innocence to like L.A.,” she writes. “It requires a certain plain happiness inside . . . to choose it and be happy here.” Any other writer in Hollywood—for whom the gold standard was the morbid conservatism of Fitzgerald or the Didion-Dunnes—might have some trepidation about choosing to be happy there, or announcing the fact. It’s more respectable to write noir about a place like that. But Babitz would rather play the ward heeler for Los Angeles. She does not see doomsday whenever she takes off her sunglasses. Her friend mocks the macabre romanticism of Joan Didion’s LA in Play It as It Lays: When the friend went to a mental institution, there were, as Babitz puts it, “no cypresses in sight, and, not only that, no one wore trench coats.”

It was Didion—another Wasser model; see Joan Didion in Front of Her Yellow Stingray, 1968—who brought Babitz’s essay on Hollywood High to the attention of Rolling Stone. This was her big break as a writer. She had been making a living, or living on the make, as a photographer and album-cover designer. Mostly she was a self-described “beach-going blonde,” an aesthete, and a party girl. The people she managed to meet provide Eve’s Hollywood with one of the more memorable front-loading devices in literary history, spoken of with a reverence elsewhere reserved for the first sixty pages of Don DeLillo’s Underworld. Her eight-page “Dedication” functions as a deeply satisfying first chapter. Among those honored are Jim Morrison, Joseph Heller, Linda Ronstadt, and Derek Taylor, who “once introduced me to a Beatle as ‘the best girl in America.’” And: “the Didion-Dunnes for having to be who I’m not.” (Presumably, LA skeptics, workaholics, and public intellectuals.)

Babitz also thanks “Andy Warhol and Paul Morrissey who I’d do anything for if only they’d pay,” and you do get the same benignly lurid pleasure from this dedication as from Warhol’s diaries. It’s funny now to think that the first edition of those diaries was published without an index, rendering it almost pointless (until Spy magazine gleefully published its unauthorized guide). Babitz’s book, on the other hand, can be slightly disappointing when you realize it warrants no index—the dazzling opener is a bit like eating dessert before dinner. I waited in vain for a choice Didion-Dunne anecdote. There are, of course, a few morsels of gossip to look forward to. In “New York Confidential,” she introduces Salvador Dalí to Frank Zappa at the King Cole Bar in Manhattan: “Frank wore a monkeyskin coat that came down to his feet. Underneath that he wore pink and yellow striped pants, shoes (it was cold) and a silken jersey basketball T-shirt in neon yellow-orange.” The doorman says he can’t come in without a tie, and hands him one:

Frank tied it in a bow. It was silver satin and not a bow tie . . .

Dalí took one look at Frank from across the room and rose to his feet in immediate approbation. If Frank was not for Dalí, Dalí didn’t care; he was for Frank.

The night ends abruptly, as does the anecdote. By the next page, Babitz is moving in with “an anarchist dealer who taught art and had red hair. He had aliases.” The book features a dizzying cast of bit characters; Babitz herself is the only star. Some people aren’t even named—amusing asides stand in for extended character assassination: “Violin players are all lovers of women to an extravagant extent, oboe players are crazy.”

Memoir can court disorganization: Lives are boring until something interesting happens, and how to account for all those years in between? Plus: Where do you put an essay on Xerox machines? Naturally, just after a brilliant chapter on Cary Grant that reads, in its entirety: “I once saw Cary Grant up close. He was beautiful. He looked exactly like Cary Grant.” I don’t mean to suggest that Babitz’s apparent haphazardness lacks any design. She does not, for instance, tell the Duchamp story, though it is undoubtedly what she is famous for. This was not meant to be an ancillary text to other artists’ lives, but to her own.

In her introduction, Babitz says: “I am really an artist, not a writer.” Not being a Didion-like writer is part of her shtick. She describes the first time she got the chance to write a book: “All at once I was home writing. I stopped going out and met no one. . . . I didn’t fuck anyone new. The writing got dismal and you couldn’t read it.” Things improved once she started writing on subjects that naturally preoccupy “daughters of the wasteland”: men, money, masks. When a girl’s “beauty arrives, it’s very exciting,” she writes, for “as with inheritances, it’s fun to be around when they first come into the money and watch how they spend it and on what.”

Babitz’s strength in analyzing LA is that she never quite saw herself as one of the beautiful people (growing up, “we knew no movie stars and we were as completely infatuated with them as everyone else”). She wasn’t born starry, and when you’ve had to make yourself that way, you understand how much art is involved: You don’t underestimate glamour or charm. It didn’t always come easy to Babitz, but she knew better than to make it look hard, so she learned to write the way she spoke. She thought the inverse—talking like a writer—could be seen as a threat. (Though no doubt she knew she was a threat: the party girl who remembers the party.) She observes how certain women refuse to acknowledge what they get for being beautiful: “Beauty, unlike money, seems unable to focus on the source of the power.” They are unwilling to admit “why they were invited.” Babitz knew why she was invited; she understood exactly what she was offering, and for how long. Just as she knew that putting herself on the cover of her book would get you to pick it up in the bookstore, the dedication would get you to buy it, and party-girl logic would have you stay all the way through to the end.

Kaitlin Phillips is a writer living in Manhattan.