One of the inevitable advantages that Liz Garbus’s recent documentary, What Happened, Miss Simone?, has over the book of the same name by Alan Light is its mesmerizing footage of Nina Simone in performance. The most arresting scene shows Simone playing at the 1976 Montreux Jazz Festival. Framed in an intimate close-up, Simone has just begun a hushed rendition of the Janis Ian song “Stars” when she suddenly lifts her right arm from the piano and extends it accusatorially toward the balcony. “Hey girl,” she chides an unseen audience member. “Sit down. Sit. Down.” She waits. And then, once the atmosphere has been recalibrated to her liking, Simone resumes a performance so wrenching, so precise, so fearlessly tuned in to her own suffering that it has, without fail, moved me to tears each of the half dozen or so times I’ve watched it.

Simone was known for shushing audience members, refusing to play until the crowd gave its full attention, and occasionally cutting shows short. Some critics wrote this off simply as diva behavior, but Simone’s longing for dignity had deep roots. At her first recital in Tryon, North Carolina, when she was ten, her parents were moved from the front row to make room for white audience members; she refused to play until they were returned to their original seats. The girl prodigy, born Eunice Waymon, took lessons from a disciplined, Bach-loving white woman and played regularly at her minister mother’s revival meetings, all the while working toward her grand goal of becoming the first black female solo pianist to play Carnegie Hall. She got there eventually, in 1963, playing pop standards instead of Bach, and never stopped wishing that listeners would give a pop performer the same respect they’d show a classical musician. As the ’60s went on, Simone wrote passionate, personal, and triumphant songs about racial injustice in America, like “Mississippi Goddam” and “To Be Young, Gifted, and Black.” In her later years, she struggled with mental-health issues and restlessly fled her home country, living for stints in Barbados, Liberia, and Amsterdam. The through line in her life was not just her dissatisfaction with the status quo but her determination to demand more—which was, and still is, a radical act for a black woman making music (or really, just existing) in America.

A more engaged audience—primed to receive her messages of revolt and liberation—was one of her demands, so it’s bittersweet that, thirteen years after her death, she is at last receiving the kind of reception she wanted. The racial disparities that Simone sang about have not gone away, though lately the #BlackLivesMatter movement has drawn fresh attention to them. And perhaps because too few contemporary musicians are making resonant protest songs (with notable exceptions like the rapper Kendrick Lamar, whose “Alright” has become the movement’s anthem), a new generation of activists has come to embrace Simone’s music. Last April, after twenty-five-year-old Freddie Gray was killed in police custody, Simone’s 1978 song “Baltimore” became a rallying cry. She has been prominently sampled on the past two Kanye West albums (one of which features her haunting version of Billie Holliday’s anti-lynching incantation “Strange Fruit”), and her name has been spoken from the podium at the two most recent Academy Awards ceremonies. “Nina Simone said it’s an artist’s duty to reflect the times in which we live,”John Legend said in 2015 as he and Common accepted an Oscar for “Glory,” the theme song from Selma. And Garbus’s much-streamed documentary was nominated for the Best Feature Documentary award, an ironic reproach in the year of the #OscarsSoWhite protests. Simone’s Oscar streak is unlikely to extend into a third year: Cynthia Mort’s recent, critically maligned biopic Nina controversially features the light-skinned actress Zoe Saldana playing Simone in darkening makeup and a prosthetic nose. As Simone was a pioneer in expanding American entertainment’s ideas about blackness and beauty, Saldana’s casting seems particularly tone-deaf. But Nina raises the question: Can anyone really hope to do justice to her provocative, unruly spirit?

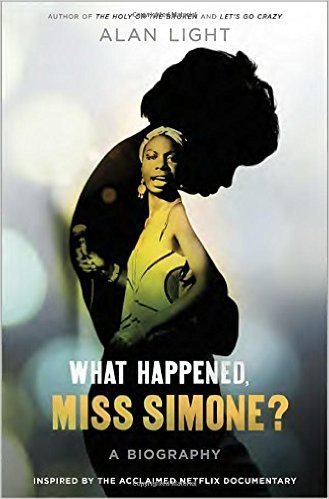

Light’s biography is an earnest attempt to get Simone right. According to an interview with the Observer, Light was given access to all the film’s research and commissioned to make use of scads of material that wasn’t included in the hour-and-forty-minute-long documentary. It’s a welcome project, because the film shied away from some of Simone’s messier contradictions: the tension between her fierce, independent spirit and her romantic attraction to domineering and sometimes physically abusive men; her desire for wealth, which complicated her ideological activism. But although Light’s book gives us more information about some of these complexities, it very often feels like a director’s-cut version of the documentary on which it was based, rather than a stand-alone statement.

In 1991, Simone published I Put a Spell on You, a lively autobiography, written with Stephen Cleary, which Light, in his introduction, calls “often fascinating, wildly inaccurate, ‘and’ maddeningly uneven.” What Happened, Miss Simone?, on the other hand, reads incredibly smoothly. Light has funneled Simone’s passionate, freewheeling journal entries and self-mythologizing interview transcripts into a rather straightforward, bland narrative. He can’t quite make Simone’s story sing. Unlike the 1970 Maya Angelou essay from which the book and documentary take their name, this is a well-organized collection of facts that too often eschews feeling. Light’s book gets all the essentials in order. But it is, of course, in the spirit of Miss Simone to ask for a little more sugar.

Lindsay Zoladz is a staff writer at The Ringer.