Lindsay Zoladz

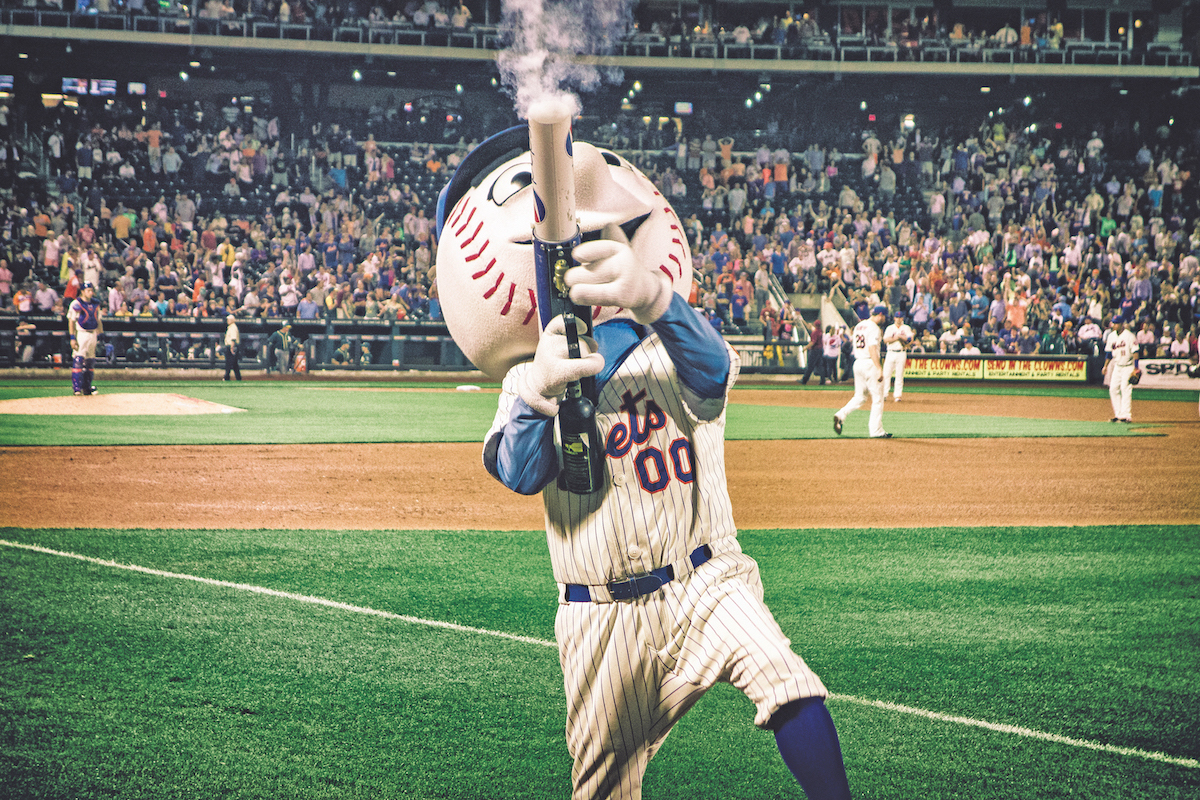

Baseball: “Inning Eight: A Whole New Ballgame” (PBS; 1994) The Mets don’t make an appearance in Ken Burns’s epic documentary Baseball until the eighth part, but they storm the scene like only they can, charting a wild ride in the 1960s from the cellar to the penthouse. Burns gives ample time to the ill-fated and slapstick-y Casey Stengel era, but the climax of the story is of course the arrival of ace Tom Seaver and the team’s world-shaking 1969 championship run. Doc Darryl (ESPN; 2016) For this entry in ESPN’s 30 for 30 series, Judd Apatow and Michael Bonfiglio staged

SEVERAL YEARS AGO, while visiting my parents’ house, I found an artifact of my tortured early years of baseball fandom. It was a journal I was assigned to keep at the beginning of first grade, a stretch of time in the autumn of 1993 that coincided with a thrillingly unexpected Philadelphia Phillies postseason run. “I like the Phillies,” I wrote on October 8—a rather bold statement, given that the Greg Maddux–led Atlanta Braves had clobbered them 14–3 in Game 2 of the National League Championship Series the night before. I added several small crayon illustrations, as if placing my modest

IN 1990, WHILE COLLECTING PERSONAL PHOTOGRAPHS for their Ohio River Portrait Project, archivists at the Kentucky Historical Society came upon an amusing, near-century-old snapshot commemorating something called the “Tacky Party” of Ballard County. Seven turn-of-the-century young adults pose for a group portrait, looking as genteel and deadpan as a team at the beginning of a Family Feud episode. They first appear to be wearing the usual sorts of garments we might picture when we think of the early 1900s: hats piled high with ornamental flowers and ribbons; billowing, floor-length dresses with lacy, chin-skimming necklines. But upon closer inspection, the modern

A PET PEEVE OF MINE is when people are shocked to find out that a great song was written relatively quickly. Of course it was, I want to say, before quoting one of many dog-eared passages in my worn copy of Natalie Goldberg’s Zen-creativity bible Writing Down the Bones, like, I don’t know, how about this one: “If you are on, ride that wave as long as you can. Don’t stop in the middle. That moment won’t come back exactly in that way again, and it will take much more time trying to finish a piece later on than completing

In November 1961, a closeted gay man in a well-tailored suit went to see an unsigned and relatively new musical group performing at a Liverpool club called the Cavern. “I was immediately struck by their music, their beat, and their sense of humor on stage—and . . . when I met them, I was struck again by their personal charm,” Brian Epstein would write in A Cellarful of Noise, his 1964 memoir about the band he would soon manage, make over, and turn into mop-topped superstars. Teasingly, referring to the open secret of Epstein’s private life, John Lennon suggested an

Twelve years ago this May, then-twenty-six-year-old Emily Gould wrote a cover story for the New York Times Magazine, chronicling her addiction to, and subsequent disillusionment with, what was then still a semi-novel cultural phenomenon: blogging. The eight-thousand-word essay made her the poster girl of the overshare: It was accompanied by a series of moodily lit bedroom photographs that Gould herself described as “vaguely cheesecakey.” “Lately, online, I’ve found myself doing something unexpected: keeping the personal details of my current life to myself,” she wrote in the final paragraph. “This doesn’t make me feel stifled so much as it makes me

“So Bert and Mary Poppins definitely used to fuck, right?” One Saturday night last winter some friends had gathered in my living room to reconsider one of our favorite childhood movies through the cracked lens of our millennial adulthood. (A very millennial thing to do: In our minds it was subversively ironic, but to the skeptical observer we just looked like a bunch of thirtysomethings so infantilized and brain-fried by pop culture and social media that we were spending the prime time of our weekend watching a Disney movie.) When he was eighteen, southern singer-songwriter Vic Chesnutt was in a car accident that partially paralyzed him from the neck down. He had been drinking and flipped his car into a ditch; no one else was hurt. Chesnutt would never walk again, but about a year after the crash he regained limited use of his arms and hands—just enough to play a few simple chords on the guitar. “My fingers don’t move too good at all,” he told Terry Gross in a 2009 NPR interview. “I realized that all I could play were . . . G, F, C—those kinds

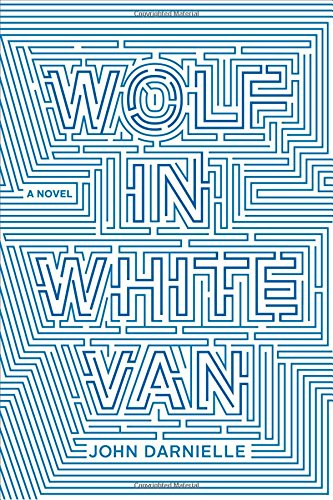

From an early age, Sean Phillips, the narrator of John Darnielle’s novel Wolf in White Van, has counted himself among a particular sect of “young men who need to escape.” Alone in his backyard in Southern California in the early ’80s, he pretended he was Conan the Barbarian; when he got a little older, he replied to small-print ads in the backs of magazines that said things like “Catalog of Rare and Unknown Swords from Around the World, Send Three Dollars and Two International Reply Coupons.” He spent countless hours—days, maybe weeks—scouring the sci-fi and fantasy sections of bookstores, seeking

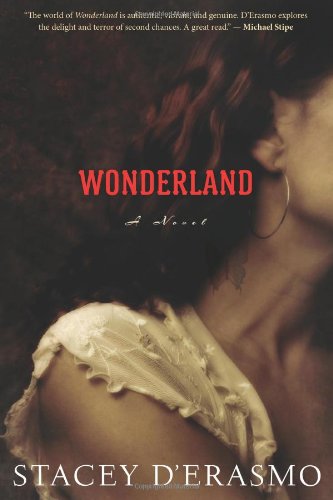

When Anna Brundage, the heroine of Stacey D’Erasmo’s Wonderland, was three years old, her father sawed a train in half and pushed it over a cliff. It was 1972, and the art world was rocked: Critics declared that he had reinvented sculpture. A postcard of the gored, upended car became a dependable seller in the MoMA gift shop. But like any creative breakthrough, Roy Brundage’s sawed-in-half train is its own kind of curse; he will spend the rest of his life attempting to recapture the unassuming wildness of that piece. He tries, prolifically, muscularly: He breaks an abandoned Texas prison