“So Bert and Mary Poppins definitely used to fuck, right?” One Saturday night last winter some friends had gathered in my living room to reconsider one of our favorite childhood movies through the cracked lens of our millennial adulthood. (A very millennial thing to do: In our minds it was subversively ironic, but to the skeptical observer we just looked like a bunch of thirtysomethings so infantilized and brain-fried by pop culture and social media that we were spending the prime time of our weekend watching a Disney movie.)

Mary Poppins, we decided, held up. There was a maturity to it we hadn’t quite remembered. The scene where Bert (Dick Van Dyke), Mary (Julie Andrews), and her charges jump inside a chalk drawing to dine with some cartoon penguins was pronounced positively “druggy,” and we clapped with delight when the Banks children withdrew their tuppence from their savings accounts and provoked an anarchic run on the bank. (#OccupyCherryTreeLane!) And so it wasn’t a stretch to speculate on the barely concealed sexual history of our heroine and the eager chimneysweep she seems to know from a vaguely gestured-toward, frequently winked-about past. “Mary Poppins, you look beautiful . . . like the day I met ya,” Bert tells her in a timelessly bad Cockney accent. A few moments earlier, his general “larking about” had provoked in Poppins a slow clap so venomous it could have wilted a plant. Just before their plunge into the chalk drawing, she snips at Bert, “Why do you always complicate things that are really quite simple?” The consensus was by then unanimous: They had a very casual arrangement, and then Mary had to end it because Bert caught feelings.

Maybe we weren’t being as cheeky as we thought. “I fancy that Mary has a secret inner life, and when you kick up your heels, you’ll catch a glimpse of who she is beneath her prim exterior,” Poppins’s Oscar-nominated costume designer Tony Walton told Andrews—they were married at the time—explaining the florid pops of pink and coral he’d sewn into the lining of her jackets and the billowing layers of her petticoats. Rivaled only by the equally prim Maria von Trapp, Poppins was the role with which Andrews’s persona was destined to be conflated for the rest of her career. It’s certainly not the worst thing to be remembered for: Poppins won her the 1965 Best Actress Oscar, and the notoriously hard-to-please P. L. Travers (author of the Poppins franchise) praised Andrews’s performance as “understated”—perhaps the greatest compliment one British woman can bestow on another.

Andrews’s iconic screen roles in Mary Poppins and The Sound of Music (which were released a year apart) still make for one of the most potent shot-and-chaser combos ever served up by a new film actress, though they did not exactly endear her to Hollywood’s burgeoning class of mavericks. Though Andrews was in her late twenties when she made these movies, she represented the old guard. Pauline Kael, in a pan of The Sound of Music so stupendously scathing that it is rumored to have been the reason she was fired from McCall’s, called the movie a “sugarcoated lie that people seem to want to eat” and singled out Andrews as “the good sport who makes the best of everything; the girl who’s so unquestionably good that she carries this one dimension like a shield. . . . Sexless, inhumanly happy, the sparkling maid, a mind as clean and well-brushed as her teeth.”

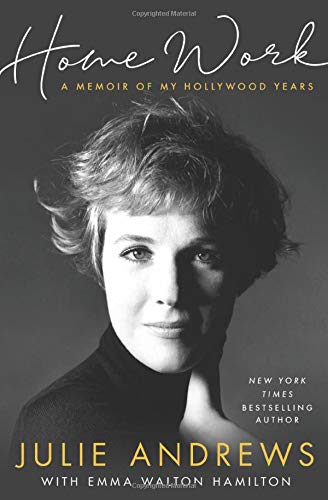

Around that time, the irreverent American filmmaker Blake Edwards said as much in private, when he and some other Hollywood types were joking, at a raucous party, about why Andrews might have won the Oscar. Edwards, who had recently directed Peter Sellers in The Pink Panther, volunteered a theory: “She has lilacs for pubic hair.” The room exploded with fateful laughter. A couple weeks later, Edwards and Andrews met in the parking lot of their respective psychoanalysts’ offices. Before he knew what was happening, he was wooing her and writing a script in which she’d challenge her image by playing a seductive, Mata Hari–esque German spy. Darling Lili (1970) bombed, but Edwards and Andrews would go on to make six more films together and, until the director’s death in 2010, stay married for more than four decades—that’s roughly four thousand years, in Hollywood time. Andrews notes in the second volume of her new autobiography, Home Work: A Memoir of My Hollywood Years (Hachette, $30): “Lilacs were a theme at every birthday and anniversary.”

On screen and off, Edwards came to see something in Andrews that Kael—and other critics like her—could not. Underneath her wimple, as the nuns say of Maria, Andrews had curlers in her hair. Yes, in nearly every role she comports herself like the queen of some imaginary, borderless kingdom. But there is also an odd tension beneath the surface of Andrews’s most ostensibly wholesome performances—the kind that can drive a viewer to all sorts of wild speculation about what Mary Poppins gets up to on her days off, and that can inspire an entire volume of queer theory that hinges upon a dissident reading of the boyish Maria von Trapp (see: Stacy Wolf’s 2002 A Problem Like Maria: Gender and Sexuality in the American Musical). Pinning down the hidden complexities and contradictions of Andrews’s stardom is a bit like holding a moonbeam in your hand. As composer and broadcaster Neil Brand put it to The Guardian last year, Andrews may just be “the politest rebel in all cinema.”

For those who missed the first volume of her memoir, the 2008 best seller Home, the ever gracious Andrews begins Home Work with a brisk, fifteen-page summary. She was born in 1935, five years before the Blitz, in a suburban village eighteen miles from London. Her parents divorced around the time the war began, and she soon moved with her mother and stepfather to ramshackle quarters in the capital. Little Jules would “sit on top of the air-raid shelter with a pair of opera glasses and a whistle,” which she would blow to alert the neighborhood when she saw the approach of pilotless German bombs known as “doodlebugs.” “One rainy day, I rebelled, and stayed in the house,” she writes. “After the bomb dropped, several neighbors came to the door, demanding, ‘Why the hell didn’t she blow her whistle?’”

It was not long before her stepfather realized she had that voice, the one that would make Captain von Trapp weep: clear, strong, as unpolluted as a desert mirage. She began singing and touring with the family act when she was ten. A year later, she performed for the queen. (“You sang beautifully tonight,” Her Highness said backstage.) But as her stepfather’s alcoholism and her mother’s depression worsened, in tandem of course, the teenage Andrews became her family’s primary caregiver and breadwinner. When Andrews was seventeen, her manager suggested that she buy out her parents’ share of their house. “It was now solely my responsibility to keep up the payments and ensure that we all had a roof over our heads,” she writes, with the no-nonsense resolve of Mary Poppins. Perhaps this is some of what she was discussing the day she met her second husband in her analyst’s parking lot.

Her movie stardom followed an already formidable Broadway reputation (she played Eliza Doolittle opposite Rex Harrison for 2,717 performances of My Fair Lady, but Jack Warner didn’t think she was bankable enough to cast in the film version; in her Golden Globe speech for Mary Poppins, Andrews thanked him for freeing up her schedule that year). From the start, she was wary of being typecast as a wonder-nanny. Unlike Van Dyke, she turned down Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, fearing it would be a Mary Poppins retread. Between Poppins and Music, she accepted the title role in the Paddy Chayefsky–penned, and decidedly adult, antiwar romance The Americanization of Emily, for the “wonderful contrast” it would provide to her film debut. In it, she plays a plucky World War II fleet driver with a terrible knack for losing loved ones when they go off to battle.

It’s a sharp, surprising film, ripe for reevaluation. I’d suggest you start with it if you’re looking for a more prismatic sense of Andrews’s career. But it’s only a warm-up for the iconoclastic movies she made with Edwards in the ’70s and ’80s, some of which found her grappling directly with the limitations of the “Julie Andrews” image. Most caustic of all is S.O.B. (1981), a pitch-black Hollywood satire Edwards began writing after Darling Lili flopped. (A forgotten detail that scandalized the press at the time: She appears topless in S.O.B., in a very meta scene about Hollywood’s insatiable lust for female nudity.) She also garnered a deserved Oscar nomination for her gender-bending performance the next year in Victor/Victoria, and, of course, played the sensible, culturally appropriate haircut to Bo Derek’s cornrows in Edwards’s 1979 hit 10.

In her personal life, Andrews was more like Mary Poppins and Maria von Trapp than any other role she’d played on-screen. From her hardscrabble vaudeville days to the itinerant lifestyle she shared with Edwards and her children—at a certain point, it starts to feel like there is more in her memoir about moving residences than moving pictures—chaos is a constant in Andrews’s life. So, then, is the act of tidying it up with a smile, whether it’s adding a spoonful of sugar to the medicine or chirpily blowing her whistle to warn her crumbling neighborhood about “doodlebugs.” As Andrews’s film presence reminds us, a cheery disposition can make us even more curious about what’s going on beneath it.

Lindsay Zoladz is a writer living in New York.