A PET PEEVE OF MINE is when people are shocked to find out that a great song was written relatively quickly. Of course it was, I want to say, before quoting one of many dog-eared passages in my worn copy of Natalie Goldberg’s Zen-creativity bible Writing Down the Bones, like, I don’t know, how about this one: “If you are on, ride that wave as long as you can. Don’t stop in the middle. That moment won’t come back exactly in that way again, and it will take much more time trying to finish a piece later on than completing it now.” The words of a poem, a song, or any other piece of writing, Goldberg says in another chapter, are simply “a great moment going through you. A moment you were awake enough to write down and capture.” Ease does not necessarily make the finished product any less great.

And yet the internet is littered with did-ya-know listicles like “7 Famous Songs Written in Less Than a Day”; “15 Hit Songs That Were Written in Less Than an Hour”; “30 Minutes or Less! 19 Famous Songs Written at Staggering Speed”—all of which treat these experiences like otherworldly anomalies rather than relatively common experiences when a talented songwriter is locked into a flow.

A storied fact that crops up near the top of every one of these lists, and which seems to go viral on Twitter every couple of months: Dolly Parton allegedly wrote two of her best and most famous songs, “Jolene” and “I Will Always Love You,” in a single night. More often than not, this feat is used as a blunt tool for productivity-shaming the rest of us mortals into submission: as one user tweeted recently, when confronted with this fact, “Maybe we should all agree to just go back to bed and try again tomorrow.”

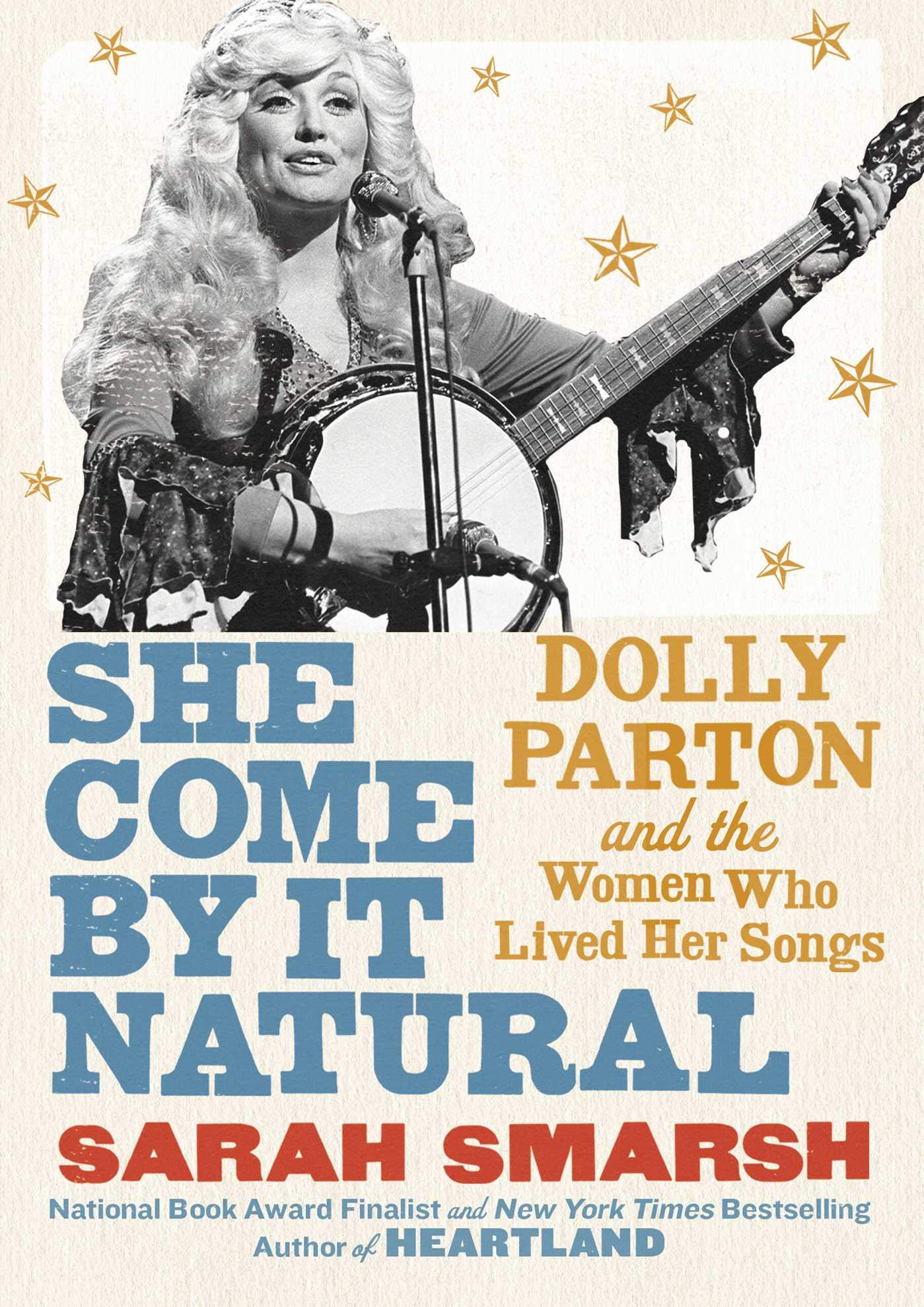

Still, this current, millennial-era fascination with Dolly Parton’s songwriting genius is certainly indicative of a larger shift in the cultural perception of her, which has over time moved away from her much-discussed figure and rhinestone-studded star persona back to her prolific, enduring songcraft. As the memoirist Sarah Smarsh writes in her new book, She Come By It Natural: Dolly Parton and the Women Who Lived Her Songs (Scribner, $22), “There is about the current Dolly fervor, I sense, an apology among some for the lifelong slut-shaming: I had no idea she was all those things. Now I understand.”

More proof of revisionist-Dolly mania: She Come By It Natural is one of two new books released in a single month that interrogate what, exactly, it means to finally take Parton seriously. The other is the Hamilton College music professor Lydia R. Hamessley’s meticulously researched Unlikely Angel: The Songs of Dolly Parton (University of Illinois Press, $20), the latest installment of the University of Illinois Press’s Women Composers series, which places the self-identified “Backwoods Barbie” in the exalted company of musicians like Chen Yi and Hildegard of Bingen.

On the face of it, this is just the sort of academic-izing that Smarsh is arguing against: “Like me,” she writes, Parton “comes from a place where ‘theory’ is a solid guess about how the coyotes keep getting in the chicken house.” Smarsh, the author of 2018’s best-selling Heartland: A Memoir of Working Hard and Being Broke in the Richest Country on Earth, sees Parton as a cross-generational kindred spirit: she was raised in transient poverty by a single teenage mother in 1980s and ’90s rural Kansas, while Parton grew up one of twelve children in an East Tennessee mountain shack that had no electricity and running water only “if we ran and got it,” to quote an oft-repeated Dollyism. The most vivid character in She Come By It Natural, though, is Smarsh’s Grandma Betty—born months apart from Parton herself—who had divorced six men by the time she was thirty-two and left countless exploitative and low-paying jobs before finally settling down with a good man and a steady gig as a secretary at the county courthouse. Like the famously politically averse Parton, Betty didn’t need to call herself a feminist; she was too busy living out an experiential kind of female independence. Observing contemporary feminism’s class-blindness, Smarsh is trying to write women like her own grandmother back into a cultural narrative that she believes has unduly ignored them. “The women who most deeply understand what Parton has been up to for half a century,” she writes, “are the ones who don’t have a voice, a platform, or a college education to articulate it.”

The sophisticated analysis of Unlikely Angel, on the other hand, occasionally made me grieve all the music theory I’ve forgotten since high school: whither those brain cells that once knew what made a scale Mixolydian? “Jolene,” Professor Hamessley informs us, “can be considered modal, specifically in the Aeolian mode”—not that Parton or her producers were necessarily conscious of that at the time. “I can say without a doubt we never sat down with guitars and started talking about modalities, Mixolydian, or whatever,” Parton’s longtime producer Steve Buckingham tells Hamessley.

Still, Parton and Buckingham were both enthusiastic to help Hamessley with her project, because, the latter writes in a foreword, “most articles about Dolly deal with her appearance, larger than life personality, and, very often, rumors.” The reflections Parton shares with Hamessley about songwriting not only illuminate that process, but, surprisingly, often line up quite well with the musicologist’s more theoretical observations. When Hamessley questions Parton about her recurrent use of “modal scales and the flat-VII chord in particular,” Dolly responds, “Well, that’s just the old mountain sound. It’s the sorrow chord.” How lovely: the sorrow chord. Their vocabularies might be different, but by any language, the patterns that Hamessley notices in Parton’s songs are intentional, deeply felt expressions of craft.

In Parton’s oft-repeated bon mots (“it takes a lot of money to look this cheap!”) and greatest-hits stage banter (during her concerts, if a man yells out, “I love you, Dolly!” she has been known to quip, “I thought I told you to go wait in the truck!”), Parton herself is such a slyly masterful curator of her own story and selfhood that it can sometimes feel like all there is to know about her—or at least all she’s going to let us know about her—is already out there. And so, as a Parton fan myself, I can’t say I learned much new information from Smarsh’s book. She Come By It Natural is at its best when it’s in memoir mode, rather than treading the well-worn road of Parton’s biography or, worse, using Parton as an all-encompassing filter through which to view and make sweeping conclusions about very recent cultural history. As in: “Women dismissing female supporters of Democratic socialist Bernie Sanders, when he opposed Clinton in the 2016 primaries, is not all that different from Barbara Walters criticizing Parton’s style choices in 1977.” Really?

Smarsh is correct to criticize feminism’s past and present waves for not talking enough about class. But her analysis often cuts a little too close to the academic-theory-indebted identity politics she elsewhere so vehemently critiques (to say nothing of her reliance on terms like “woke,” “problematic,” and, yes, “slut-shaming”). Her read cannot quite explain the vast spectrum of Parton’s fan base, which includes conservative grandfathers, young queer folks, and just about anybody in between.

Hamessley gets closer, in a final chapter about Parton’s spirituality, and provides a more spacious read of her appeal. Here she quotes Dolly, telling her concertgoers she’ll be their mirror: “A lot of times my fans don’t come to see me be me. They come to see me be them. They come to hear me say what they want to hear, what they’d like to say themselves, or to say about them what they want to believe is true.” In this way, Hamessley notes, Parton quite literally assumes the role of healer.

The fine, affectionate attention Hamessley pays to Parton’s music offers all sorts of revelations: the old-world strangeness of Parton’s lyrical diction (“My life is like unto a bargain store . . .”), the Appalachian roots of the stirringly beautiful chest voice she employs on her 2002 song “These Old Bones,” or how much more eerie her critically maligned tearjerker “Me and Little Andy” becomes when you consider it within the gothic tradition of the ghost story. Hamessley’s is not the cold, ivory-tower pontification that Smarsh criticizes a bit too stridently in her narrative; it is instead a reminder of how warm any form of extended attention can be.

Songwriters work in mysterious ways. The cultural fascinations with, and frequent misunderstandings of, their processes only prove how difficult it is to write lucidly about them. Unlikely Angel, though, finally puts this version of Parton into focus. Sometimes, we learn, Parton will travel to a remote location with her best friend Judy Ogle to work without interruption for weeks at a time, so locked in that she forgets to eat. “Just about the time my blood sugar gets low,” she says, Judy will “be there with a bowl of Jell-O.” When she’s writing for “concentrated intervals,” she says, “the external world falls away.” So intimate is the portrait Hamessley paints that it is suddenly not difficult to picture Parton—tapped into an extended moment of creative reverie, an untouched, jiggling bowl of gelatin at her side—putting the finishing touches on “Jolene” and reckoning that she still has a little gas left in the tank for something else.

Lindsay Zoladz is a writer in Brooklyn.