Nicotine is further proof that Nell Zink has one of the finer imaginations in fiction today. Also a tin ear: “He steps out into the angled light of early fall, which is creating colorful geometric patterns on the fawn-colored carpet via prismatic glass in the Glasgow-style transoms of the French doors facing west.” I don’t read Zink for these stilted autodidactic flourishes—for that I prefer John Kennedy Toole, with whom she shares a trademark comical pathos.

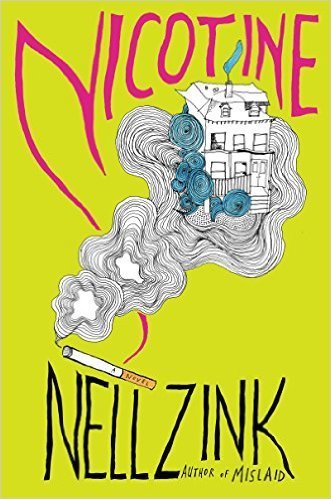

In her previous books, The Wallcreeper (2014) and Mislaid (2015), Zink has grounded her wandering style in philosophical questions about topics that some might consider hefty: sex, kinship, identity politics (usually appropriation), domestic trauma, environmental doom. Zink’s third novel tells the story of Nicotine, an anarchist squat in Jersey City whose members are burdened with defending their addiction to big-business tobacco. Sorry, the de facto house mother, complains of their persecution thusly: “Same baby who’s sucking on a nipple full of phthalates, eating antibiotic chicken, breathing PCBs, playing in dirt made of tetraethyl lead and drinking straight vodka while it rides a fucking skateboard—when that baby dies at age eighty-six instead of ninety, it’s going to be because you lit a cigarette in a public park.” Wary perhaps of constantly perjuring themselves in the anarchist community—forever caught in the crosshairs of irony—the five roommates at Nicotine cheerfully embrace the gravitational pull of shared ideology. Nicotine is not unlike a gated community within a leafy suburb, and its inhabitants are not unlike average Americans failing to contribute to the national character anything sturdier than a blithe indifference to being called stupid.

“Find your tribe and burn your bridges,” Sorry unwittingly instructs Penny, the

protagonist, who shows up on Nicotine’s doorstep. Penny’s father has died. This was his childhood home. And so we have our plot: Will Penny forsake her birth family for this self-elected tribe of antigovernment tobacco enthusiasts? Or will she kick out the squatters?

Penny’s is a family tree marred spectacularly by blight: Her father, Norm, was the patriarch of a new-age cult for the terminally ill. He gave his followers psychedelics to distract them. (“The cult is populated by realist aesthetes. A cult of personality for those cultivating personality.”) Norm went to Colombia, and brought back Amalia, a thirteen-year-old native Kogi he found wandering in a garbage dump. Zink’s appetite for grotesque incident is on full display in this almost comically baroque backstory: Norm’s wife raises Amalia with their two sons, Patrick and Matt. Matt sexually abuses Amalia. Norm’s wife disappears. Amalia and Norm conceive Penny. A twelve-year-old Penny falsely accuses Matt of rape. This is neither here nor there, trust me, and a fine example of Zink’s love of the unseemly detail. Anyway, today, Amalia loves Matt. Matt hates everyone, but especially Amalia. No one loved Norm but Penny. Norm loved them all, but…leaves no paper trail: no adoption papers, no wedding license, no will. Perhaps his savior complex waxed and waned, like a summer tan.

Moral inelegance and emotional negligence, certainly, cast a dark shadow—perhaps too dark, leaving the reader wandering about in the night. That Norm loses his ability to speak before Penny can transcribe his “confessions,” as requested, is an authorial miscalculation. If not laziness. In place of a satisfying portrait of the personality that inspired the cult, and the father who took great artistic license with the construction of his nuclear family, we get a generic liberal-leaning fogey deteriorating without much dignity in a hospital bed. “I’m an enlightened person,” Norm cracks to a nurse. “Not like a Zen Buddhist! Enlightened as in the Enlightenment.” He “croaks, ‘I don’t want to die.’” His cat visits and scratches him, and he gets blood poisoning. “His bare arms are spotted with subcutaneous pools of purple.” Not that anyone in the family, certainly not the sons, were trying to speak to him. He dies, and Penny’s mother “comes home from work early—around five—because of the special occasion.” Penny wonders if everyone in her family is a “heartless sociopath.”

This novel is preoccupied with the commonplace injustices of love in America: Why do humans choose, again and again, non-mutual symbiotic relationships? What binds one to a tribe, if not blood or love? Very little, beyond sex—few characters in Nicotine act without libidinal motivation. In fact, Penny doesn’t have to change to fit in at Nicotine, easily wriggling into a less aesthetically dubious identity: from undercover landlord to posh anarchist. She has a crush on Rob, thirty, a prickly bike mechanic who lives at the squat. He too has a secret (a very tiny penis) that he protects by pretending to be celibate. He pretends to be an asexual white man (proud) instead of an angry white man guarding his manhood (patriarchal)—Zink loves a poseur. He comfortably lounges behind the thick veil of his borrowed sexual orientation. It is no doubt gauche for Rob to appropriate another’s identity to cover up his own insecurities, but so too is a man who courts sexual grievance. It’s as if Zink feels that, global warming aside, there is no greater threat to civilization than a man finely tuning his persecution complex in bed. Rob’s eleventh-hour confession is touching—for once not in spite of but because of all the zany Zinkisms: “I always wanted to be a heavy-hung stud and impale women on my prong until they’re helpless, quivering protoplasm.”

Penny doesn’t get a chance to sever her umbilical cord. Deus ex machina style—call it the invisible hand of plot—her brother Matt shows up, claims that he owns the house, and begins obsessively trying to date Jazz, another anarchist. (Her mother does too, rather unnecessarily.) Matt shares an identical sexual fantasy with Rob, imagining that Jazz has “the look of impaled protoplasm” after they have sex. Zink’s point is corny and creepy: No matter what tribe they’re a part of, sex reduces all humans to their basic cellular component. Rendering all unhappy family members alike. And freeing them up to ruin new families.

Kaitlin Phillips is a writer living in New York.