Kathleen Collins, one of the first African American women to write and direct a feature-length work, completed Losing Ground, her second (and final) movie, in 1982, though it did not receive a proper theatrical release until 2015. Loose and effervescent, the film stands as a superb portrait of a marriage between two ambitious members of the creative class. They’re still in love after a decade together, yet strains in the union are beginning to show. Their conversations, with each other and with those in their larger orbit, are about art and ideas—topics rarely discussed on-screen, then or now, with the wit and intelligence evidenced in Collins’s film. Perhaps cinema’s first black-female-intellectual protagonist, Sara (Seret Scott), a philosophy professor, is currently researching “the ecstatic experience” and reads Saint Genet during her downtime; Victor (Bill Gunn, another under-celebrated genius), an abstract painter, drolly notes to Sara after selling one of his paintings, “Your husband is a genuine black success.” The line has a sardonic bite, slyly underscoring Victor’s uneasiness with the qualifying “black” in his boast.

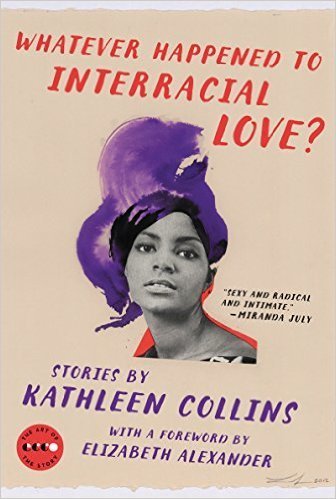

Success of a sort has finally arrived for Collins, almost thirty years after her death (she succumbed to breast cancer in 1988, at age forty-six). Thanks to the rediscovery and restoration in 2015 of Losing Ground, which received a pitiful number of screenings in the years after it was made, a once-little-known film can now be appreciated as a crucial work of American independent cinema. And with the release of Collins’s Whatever Happened to Interracial Love?, a collection of never-before-published short stories, her writing joins another kind of canon, of fiction that nimbly renders complex lives and inner tumult without pieties or clichés.

Several of the sixteen undated pieces here begin brilliantly, their first lines announcing the élan that follows. “Okay, it’s a sixth-floor walk-up, three rooms in the front, bathtub in the kitchen, roaches on the walls, a cubbyhole of a john with a stained-glass window,” opens “Exteriors,” the first story, composed as a series of lighting cues. Embedded within these lively, seemingly impersonal instructions, though, is the history of an unraveling relationship: “Now find a nice low level while they’re lying without speaking. No, kill it, there’s too much silence and pain.” The tension between these high-spirited commands and the emotional chaos they simultaneously conceal and lay bare recalls the film-within-a-film in Losing Ground, in which Sara stars in a boisterous student’s reimagining of the folk ballad “Frankie and Johnny”; the excitable directions behind the camera hint at some of the real agony Sara is enduring at home.

Collins plumbs pain in greater detail in “The Uncle,” about a former track star, who “one night . . . cried himself to death.” This is not hyperbole but the result of a metastasizing depression: a life that was ultimately restricted to the edges of a bed, on which the unnamed first-person narrator’s adored uncle consumed “huge submarine sandwiches, hot chocolate, powdered doughnuts, and ice cream” ordered “from the luncheonette around the corner.” The narrator regards this piece of furniture, where the uncle’s appetites could never be slaked and his misery never ameliorated, not necessarily as a site of abjection but as “a monument to his perverse pursuit of humiliation and sorrow.”

That abasement, however rooted in private sorrow, also stems from ineluctable reality, from “the blunt humiliation of his skin, with its bound-and-sealed possibilities.” In addition to these sharp acknowledgments of racism’s corrosive effects, Collins’s broader discussion of race in these stories amplifies that found in Losing Ground: She is ever alert to the sentimentality that attaches to narratives about black life, a mawkishness that obscures and dishonors hard truths. In Collins’s film, Sara’s mother, a stage actress played by Billie Allen, wryly explains over dinner that in her latest production, her character is “a beacon of strength and humility” in “a thoroughly colored play.”

The trappings of the genre so piquantly described by Sara’s mom are repeatedly interrogated in Collins’s fiction. “It is difficult to separate this story from the slight props of race necessary to bolster it up,” the narrator explains in “The Uncle,” the word props being somewhat ambiguous—as in a buttress? Or a theatrical set dressing?—but the diminishing adjective before it all too precisely deployed. In the story that gives the collection its title, racial categories are consistently enclosed in scare quotes, perhaps to point out their absurdity, their inaccuracy: “It’s the year of ‘the human being.’ The year of race-creed-color blindness. It’s 1963. One roommate (‘white’) is a Harlem community organizer. . . . The other roommate (‘negro’) has just surfaced from the jail cells of Albany, Georgia. She is twenty-one and the only ‘negro’ in her graduating class.”

This story, which describes the terrors of freedom-fighting in the Jim Crow South, is one of the few entries to explicitly address activism (Collins volunteered with SNCC in 1962 and was imprisoned twice in Georgia). Other types of conflict, like the brutality of intimacy, are anatomized just as piercingly. “And what of love, instead of politics?” goes the first in a string of seemingly rhetorical questions in “Whatever Happened to Interracial Love?,” the title itself perhaps an insoluble query. But Collins offers some answers. After couples disintegrate in these pieces, women often, like the character in “Interiors” identified only as “wife,” embrace “a benevolent solitude,” one that does not preclude carnal pursuits. They are sometimes desolate, inconsolable, but never self-pitying. “I snipped and pasted . . . snipped and pasted, pouring into my masterpiece the frenetic, absorbed posture of the woman artist at work,” Collins writes of the protagonist in “Interiors,” who takes up a series of creative occupations and avocations. “Woman artist” here carries the same sarcastic kick as “genuine black success” does in Losing Ground. The term suggests another category that Collins, in a singular body of work that was overlooked during her too-short life, most likely found too limiting.

Melissa Anderson is the senior film critic for the Village Voice.