Melissa Anderson

WRITTEN MORE THAN a decade after Stonewall but taking place five years prior to it, Jane DeLynn’s In Thrall is a grimly comic tale of dyke awakening. This 1982 novel, reissued by Semiotext(e), recounts the sexual relationship—at once pitiful, elating, and perverse—between the book’s first-person narrator, Lynn, a sixteen-year-old senior at a selective all-girls high […]

TO TRAVEL FROM Massapequa Park, a small town on Long Island, to Penn Station on the LIRR takes about an hour. It was a commute that Candy Darling made countless times between 1962, the year she turned eighteen, and 1974, the year she died, at age twenty-nine. The return trip from Manhattan—where she would first meet Jackie Curtis, Andy Warhol, Paul Morrissey, Jane Fonda, Werner Schroeter, and so many other important collaborators and friends—often required Candy to travel under the cover of dark and to take a cab from the station directly to the Cape Cod house where her mom,

I HAVE FREQUENTLY BEEN SEATED in the dark near those who have variously been called “the pilly-sweater crowd,” “cinemaniacs,” or “Titus-heads” (referring to the two main movie theaters at MoMA). They are pejorative terms for a certain type of New York City cinephile, one whose zeal for the seventh art seems to have been leached of all pleasure and has instead transmogrified into grim compulsion. Demographically, they are often (but not always) white, male, and middle-aged or older.

PUBLISHED IN 1974, Patricia Nell Warren’s best-selling novel The Front Runner, about the same-sex intergenerational romance between Harlan Brown, a college track coach, and Billy Sive, his star athlete, capitalized on dual booms from that decade: the running craze and the growing crossover appeal of LGBTQ+ literature.

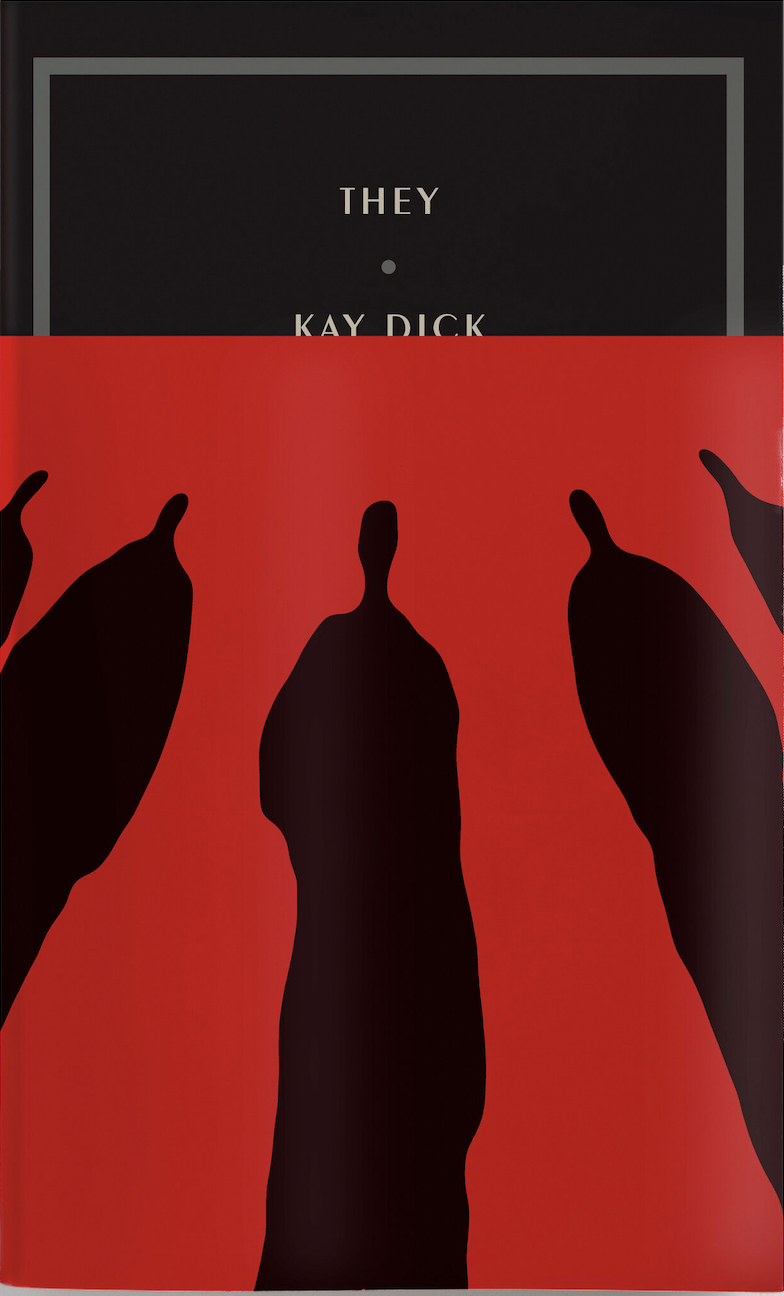

THE WRITER AND THE NOVELLA were both new to me: two plosive proper nouns and one personal pronoun, adding up to just three potent monosyllables. Kay Dick (1915–2001): an indelible name, especially for a lesbian. They: her ninth book (and sixth work of fiction), published in 1977, and best summed up, per text on this slim volume’s title page, as “a sequence of unease.”

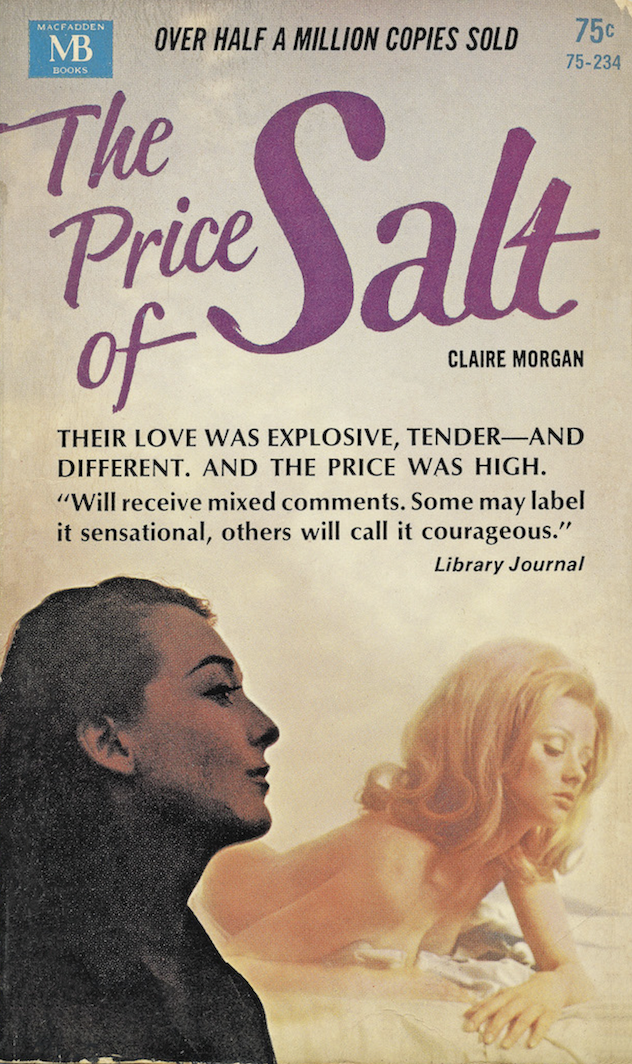

IN AN AFTERWORD WRITTEN to accompany the 1990 reissue of her second novel, 1952’s sapphic paragon The Price of Salt, Patricia Highsmith insisted, “I like to avoid labels,” taking umbrage even at being called a suspense writer. The declaration functioned somewhat as a misdirection, deployed to explain why she published the book pseudonymously (as Claire Morgan), though not why she refused until almost forty years later to publicly acknowledge—and thus out herself—that she was the author of this swoony tale of same-sex romance: “If I were to write a novel about a lesbian relationship, would I then be labelled a

THE CONCEPT OF THE MASK, of concealing, is made explicit in the title of Persona, Ingmar Bergman’s superlative film of 1966. Yet ever since its release, many critics and viewers have sought to uncover the “meaning” of this enigmatic work, which centers on the relationship between two women: Elisabet Vogler (Liv Ullmann), an actress who stops speaking, and Alma (Bibi Andersson), a nurse tasked with overseeing Elisabet’s convalescence. Bergman cautioned against the urge to demystify, remarking to a Swedish TV journalist in 1966, “Each person should experience it the way they feel.” Ullmann, in 2013, was even blunter, insisting that

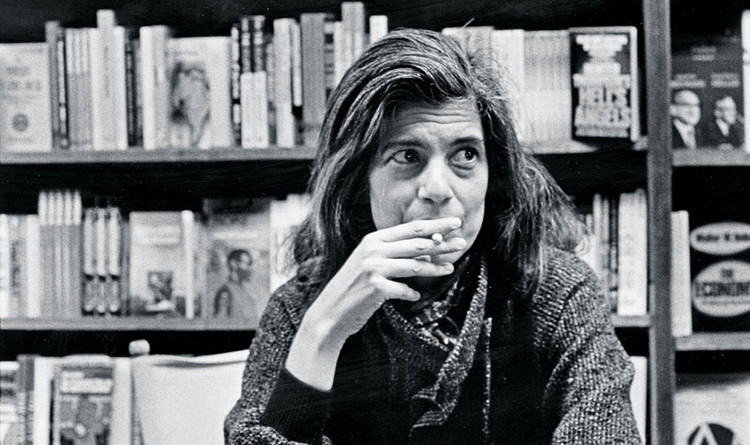

What was Susan Sontag’s preferred pronoun: “I” or “one”? First- or third-person singular? Which of those substitute-words revealed—or concealed—more about the woman who reigned as the leading cultural authority during the second half of the twentieth century but who refused to explicitly acknowledge her same-sex relationships? From the second paragraph of “Notes on ‘Camp’” (1964): “I am strongly drawn to Camp, and almost as strongly offended by it. That is why I want to talk about it, and why I can.” (The declaration all but trumpets her membership in the lavender mafia.) Toward the end of that career-launching essay, in

First published in 1952, Lillian Ross’s Picture, an eyewitness report of director John Huston’s adaptation of The Red Badge of Courage, remains the paradigm of a slim genre, the nonfiction account of a movie’s making (and unmaking): from shooting to editing to studio meddling to publicity planning to preview screening to more studio meddling to, finally, theatrical release. The book is populated by raffish heroes (Huston) and tyrannical philistines (Louis B. Mayer), by the beleaguered (producer Gottfried Reinhardt) and the overweening (MGM head of production Dore Schary), and by various hypocrites, toadies, greenhorns, and wives. Envisioned by Ross as “a

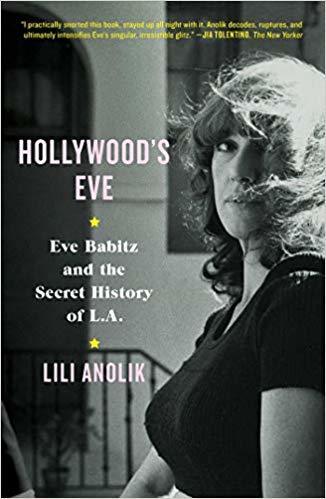

After decades of obscurity, Eve Babitz—the marvelous polymath of pleasure and gifted annalist of the delights and despair of Los Angeles, where she was born in 1943 and still resides—was suddenly everywhere. The Babitz revival began in early October 2015, with the reissue of her first book, Eve’s Hollywood (1974), the celebrated eight-page dedication of which is dotted with the names of various SoCal demiurges of the 1960s and early ’70s who made up her milieu. They included, among many others, several artists associated with the Ferus Gallery (including Ed Ruscha; Babitz is featured in his Five 1965 Girlfriends), Linda