After decades of obscurity, Eve Babitz—the marvelous polymath of pleasure and gifted annalist of the delights and despair of Los Angeles, where she was born in 1943 and still resides—was suddenly everywhere. The Babitz revival began in early October 2015, with the reissue of her first book, Eve’s Hollywood (1974), the celebrated eight-page dedication of which is dotted with the names of various SoCal demiurges of the 1960s and early ’70s who made up her milieu. They included, among many others, several artists associated with the Ferus Gallery (including Ed Ruscha; Babitz is featured in his Five 1965 Girlfriends), Linda Ronstadt (for whom Babitz designed album covers), and Jim Morrison (another lover). Since then, her four other memoirs (masquerading under the name “fiction”) have been republished: Slow Days, Fast Company (1977), Sex and Rage (1979), L.A. Woman (1982), and Black Swans (1993). Hulu is developing a series based on the first four books, to be called LA Woman. She is a popular hashtag on Instagram.

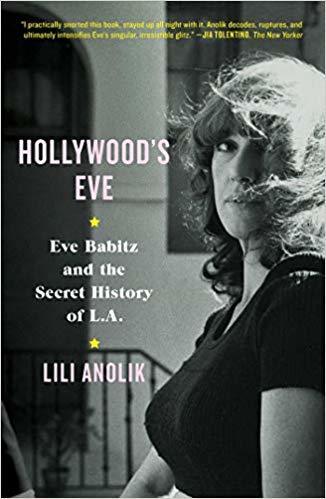

Catalyzing the renewal of interest in the cult author was a feature in the March 2014 issue of Vanity Fair by Lili Anolik, her first article for the magazine, titled “All About Eve—and Then Some.” Anolik, now a contributing editor at the Condé Nast monthly, has expanded that piece into a bumptious book-length profile. I haven’t used the word biography, for Anolik doesn’t care for the term. “Hollywood’s Eve isn’t a biography—at least not in the traditional sense,” she declares, in the very first sentence. By the fourth, she grabs us by the lapels and sets us straight: “Here’s what Hollywood’s Eve is: a biography in the nontraditional sense; a case history as well as a cultural; a critical appreciation; a sociological study; a psychological commentary; a noir-style mystery; a memoir in disguise; and a philosophical investigation as contrary, speculative, and unresolved as its subject. Here’s what Hollywood’s Eve is above all else: a love story. The lover, me. The love object, Eve Babitz, the louche, wayward, headlong, hidden genius of Los Angeles.” But is this book really a reflection of Anolik’s amour fou—or amour-propre, an intoxication with her own mannerist way of writing?

This grandiose style works well—or can work well—for a text in the five-thousand-word range; it exhausts and exasperates when deployed in a book close to three hundred pages (I was depleted after the first paragraph). It is also jarringly at odds with that of the writer being lionized. Babitz, a sybarite with a sinuous sensibility, casually festoons her prose with offbeat aphorisms, like this one, from Sex and Rage: “People go through life eating lamb chops and breaking their mother’s hearts.” Her “I” is simultaneously vigorous and nonchalant. “I did not become famous but I got near enough to smell the stench of success,” she writes in Slow Days, Fast Company, alluding to the period right after Eve’s Hollywood was published.

Anolik inserts herself much less gracefully. A belabored section that aims to knock down Joan Didion—who, along with husband John Gregory Dunne, was an early champion of Eve’s—and boost Babitz as the quintessential chronicler of Southern California concludes with a tantrum: “I think Play It [as It Lays] is a silly, shallow book. I think Slow Days should replace it, become the new essential reading for young women (and young men) seeking to understand L.A. There. I said it.” My response to this rhetorical fillip was the same as Didion’s in an infamous 1979 letter exchange with a reader miffed over her takedown of Woody Allen in the New York Review of Books: Oh, wow.

As for the “Secret History” teased in the subtitle of Anolik’s book, she does deliver, helpfully identifying several of the figures discussed pseudonymously in Babitz’s work (whether those books use the first-person pronoun or the third) and often discussing them at length. This straightforward reporting arrives as balm, both dishy insight into Eve’s rarefied circles and a welcome respite from Anolik’s excitable neo–New Journalist tics. We learn, for instance, that the venomous charmers of Sex and Rage called Max (who Babitz, with typical piquant precision, says “smelled like a birthday party for small children”) and Etienne (“built like a lizard or a saluki”) are Earl McGrath and Ahmet Ertegun. The former was a bisexual bon vivant and one of the dedicatees of Didion’s The White Album; he was also the unofficial majordomo to—and, per Anolik, a “procurer” of bedmates for—the latter, the president of Atlantic Records and one in a long line of Eve’s married inamoratos. One of the most vivid characters in Slow Days, Fast Company, the aspiring singer and actress and sometime smack user “with cheeks the color of baby’s feet” dubbed Terry Finch, turns out to be Ronee Blakley, who indelibly played the unstable country-music superstar Barbara Jean in Robert Altman’s superb Nashville (1975).

And Anolik’s claim from her hyperactive intro that her book on Babitz is “a memoir in disguise” is also borne out, if queasily so. She spares no detail in her quest to track down Babitz, a mission that began in 2010, apparently launched by a false memory: Anolik, thirty-two at the time and living in New York, swears she first became aware of Babitz thanks to a quote attributed to her in screenwriter Joe Eszterhas’s memoir Hollywood Animal (2004), but comes to realize that no such passage exists, in that book or any other by Eszterhas. She finds used copies of Eve’s novels, then long out of print, online—where Babitz herself, with no social-media presence, could not be found. She was, however, in the phone book; Anolik mails a postcard to, then starts calling, Eve at her West Hollywood residence, where she had been living as a near recluse since 1997, when a mishap with a cigar led to third-degree burns over half her body.

After two years of ignoring these messages, Babitz finally agrees to have lunch with Anolik, who has by now received encouragement from Vanity Fair, though her pitch has yet to be officially accepted. That initial meeting is strained; Babitz wolfs down her food and says little. (The encounters would grow more relaxed though never entirely comfortable. Anolik has a much easier rapport with Babitz’s younger sister, Mirandi, who proved crucial to the project and is also profiled here.) Anolik refuses to be deterred: “That Eve, famous for her beauty and seductiveness, was now a ruin and a gorgon excited me. It heightened the beauty and seductiveness of her books, reinforced my conviction that she was an artist and an original.” Later in that same paragraph, Anolik makes a bolder confession: “Then there was this: she was my ticket out of publishing purgatory—anonymous writer-for-hire assignments, dry-as-dust magazines that barely paid—I was sure of it. It was starting to dawn on me how ambitious I was, how far I was willing to go. It was starting to dawn on me that I might be a gorgon too.”

Perhaps Anolik’s naked admission of her zeal—or what might less charitably be called her careerism—is a sign of her daring candor. Or maybe it’s just more ostentation. The disclosure, at the very least, undermines Anolik’s insistence that Hollywood’s Eve is also “a love story.” Anolik, we discover, unequivocally adores only one of the books in the Babitz stealth-memoir pentad: Slow Days, Fast Company, which she hails as “an authentic masterpiece” and “the book that made me want to write this book.” She deems Eve’s Hollywood, however, “not a mature or disciplined work,” adding that “certain pieces, you don’t know what they’re doing there.” The judgments grow harsher. “I don’t like Sex and Rage and regard it, in spite of its killer title, as a failure” is followed by an even more derisive assessment: “If Sex and Rage was the beginning of downhill for her, L.A. Woman proved that the slide wasn’t stopping soon.” She gives the final volume in the quintet a backhanded compliment: “Black Swans isn’t up to Slow Days, doesn’t have that breadth or magic. It’s a good, serious work, though, and a marked improvement over Sex and Rage, certainly over L.A. Woman.” (Anolik is a fan of Babitz’s 1991 Esquire piece on Jim Morrison and her 1980 book on the Italian fashion label Fiorucci. Two by Two, Babitz’s 1999 volume on the tango scene in LA and her last published book to date, Anolik calls “slight.”)

What Anolik appears to really love is the idea of Babitz. Or more specifically, Babitz as the inverse of Anolik, who wonders about her subject, “Is the fascination she exerts over me simply that of the Other—she’s an adventuress and sexual outlaw, and I’m married to my [male] college sweetheart, have never taken a drug, am as compulsively abstemious as she is compulsively excessive, and I therefore can’t get enough?” But that awe is disingenuous. Later, Anolik seems to pity Babitz for not being Anolik—that is, a wife, a mother, financially secure, ambitious. Never married, forgoing the conventional path Anolik has followed, mostly dormant since her accident, Eve is labeled “a child,” one who will never grow up: “She was beholden to nothing and no one—not a man or kids, or a piece of property, or a boss, not even to an audience. Adulthood was a condition she simply wouldn’t submit to, and that was that.”

This is narrow-minded, condescending, and sanctimonious. I doubt Babitz will care. She had already shrewdly summed up the likes of Anolik in this passage from Sex and Rage, about the frantic desperation of editors at a certain kind of New York magazine: “They had to be at every birth of a new trend, every debut, every next year’s event, or person, or gang war.”

Melissa Anderson is the film editor of 4Columns and a frequent contributor to Bookforum.