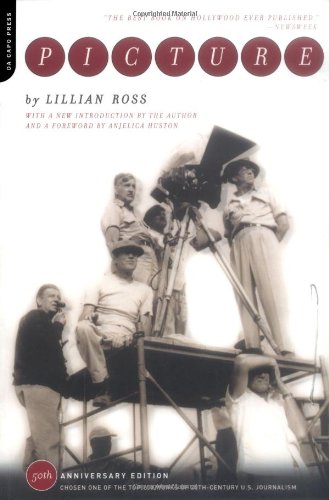

First published in 1952, Lillian Ross’s Picture, an eyewitness report of director John Huston’s adaptation of The Red Badge of Courage, remains the paradigm of a slim genre, the nonfiction account of a movie’s making (and unmaking): from shooting to editing to studio meddling to publicity planning to preview screening to more studio meddling to, finally, theatrical release. The book is populated by raffish heroes (Huston) and tyrannical philistines (Louis B. Mayer), by the beleaguered (producer Gottfried Reinhardt) and the overweening (MGM head of production Dore Schary), and by various hypocrites, toadies, greenhorns, and wives. Envisioned by Ross as “a fact piece in novel form, or maybe a novel in fact form,” Picture endures as a key work of proto–New Journalism. Though Ross, a writer for more than sixty years at the New Yorker—where Picture, under the title “Production Number 1512,” was first published, in five installments—was renowned for her fly-on-the-wall reporting, she is not always invisible in the book; “I” pops up intermittently.

Ross is especially transparent in her introduction to the fiftieth-anniversary edition of Picture from 2002—included in the current reissue from NYRB Classics—in which she discusses one of the factors that led her to accept Huston’s invitation, extended in 1950, to follow him and the production of The Red Badge of Courage. “I actually was taking that opportunity to try to escape from my personal entanglement with my editor, William Shawn,” she writes. “He was then the managing editor of The New Yorker and was married, with young children. He had told me he was in love with me; I was in love with my work, and I was becoming dangerously drawn to him. I had intended to stay in Hollywood a few months; I stayed for a year and a half.” This confession appeared four years after the publication of Ross’s semi-scandalous memoir from 1998, Here but Not Here, a glowing remembrance of her four-decade affair with Shawn—a relationship that began in earnest when she returned to New York after her eighteen-month Los Angeles sojourn. Picture, considered Ross’s signature achievement as a reporter, might be thought of, then, as an oblique prequel to the book regarded (primarily by the ex–New Yorker staffers who reviewed it and/or were mentioned in it) as her most unseemly.

If Picture came about, in part, from a wish to avoid a deepening romance, it also provided an opportunity to solidify a burgeoning friendship. As Ross details in the introduction, she first met Huston while in Hollywood to report a piece, published in a February 1948 issue of the New Yorker, about the effects of the red-baiting hysteria of the House Un-American Activities Committee on the film industry. “Conversation with him was like fresh air,” she notes of those initial encounters. After the article ran—Huston liked it—the two began an “unusual friendship” that lasted until his death, in 1987; she would write at least three other pieces for the magazine about the actor-director. (Ross died in 2017, at age ninety-nine.) “Hanging out with him was always high-spirited fun; it invariably felt as though I were part of one of his dramatic, intriguing movie scenes,” Ross recalls.

Anjelica Huston, who was born a few months before her dad’s movie opened in 1951, also joins the love-in. In her foreword to the 1993 edition, also reprinted in the NYRB reissue, she writes, with a touch of sanctimony, “It was my father as an artist that fascinated Lillian Ross. She never sought to write gossip or to go beyond a particular line that she drew for herself in his personal life.” To illustrate why her parents “loved,” “respected,” and “trusted” the New Yorker writer, Anjelica includes a long excerpt from Ross’s introduction to her 1964 book, Reporting, part of which reads:

Just because someone “said it” is no reason for you to use it in your writing. Your obligation to the people you write about does not end once your piece is in print. Anyone who trusts you enough to talk about himself to you is giving you a form of friendship. . . . If you spend weeks or months with someone, not only taking his time and energy but entering into his life, you naturally become his friend. A friend is not to be used and abandoned; the friendship established in writing about someone usually continues to grow after what has been written is published.

The passage, insisting on journalism as an act of amity, alarms. (Taken to the extreme, the words have inspired countless mediocre celebrity profilers to post selfies with their subjects as a trophy.) It seems hopelessly sanguine and square compared with later, scaldingly self-abasing definitions of the profession. Four years after Ross’s Reporting, Joan Didion concluded her preface to Slouching Towards Bethlehem with this pronouncement, the original italics adding maximum chills, as if she got up from her typewriter, looked in the mirror, and saw REDRUM scrawled all over it: “Writers are always selling somebody out.” In 1989, Ross’s New Yorker colleague Janet Malcolm would infamously define a journalist as “a kind of confidence man, preying on people’s vanity, ignorance, or loneliness, gaining their trust and betraying them without remorse.”

More to the point, Ross’s cheery Reporting 101 principle is disingenuous—and frequently violated in Picture. But that contradiction is what makes the book such a fizzy pleasure. Not everyone is a “friend.” “I happen to like forthright, up-front crooks and villains, and I gloried in finding some of them in Hollywood,” she writes in Picture’s introduction. The most contemptible of the book’s figures, unsurprisingly, is studio boss Mayer, the savage sentimentalist who never hid his antipathy toward Huston’s adaptation of Stephen Crane’s Civil War novel. Scribbling in three-by-five-inch notebooks, Ross waits for the damning quote—which, in the movie mogul’s case, means simply waiting for him to open his mouth. This staccato outburst typifies Mayer’s vulgar grandiosity:

“Art. The Red Badge of Courage? All that violence? No story? Dore Schary wanted it. Is it good entertainment? I didn’t think so. Maybe I’m wrong. But I don’t think I’m wrong. I know what the audience wants. Andy Hardy. Sentimentality! What’s wrong with it? Love! Good old-fashioned romance!” He put his hand on his chest and looked at the ceiling. “Is it bad? It entertains. It brings the audience to the box office.”

More insidious is Schary, who at first presents himself as an ally to Huston and Reinhardt—and more generally, as an executive who understands, and will champion, Mayer’s loathed “art.” Ross notes the bronze plaque with a Ruskin quote in the reception area outside Schary’s office. During her first meeting with Schary, at Chasen’s restaurant, she is alert to his self-importance:

He spoke earnestly, as though trying to convey a tremendous seriousness of purpose about his work in motion pictures. “A motion picture is a success or failure at its very inception,” he told me. “There was resistance, great resistance, to making The Red Badge of Courage. . . . The story—well there’s no story in this picture. It’s just the story of a boy. It’s the story of a coward. Well, it’s the story of a hero.” Schary apparently enjoyed hearing himself talk.

Though Schary will later tell Ross he thinks Huston’s film “is a beautiful picture . . . a moving, completely honest, perfect translation of the book,” he demands major cuts and the inclusion of a distracting, redundant narration, which he partly wrote. (The film, which I watched on iTunes, runs sixty-nine disjointed minutes.)

Mayer and Schary are easy, and justifiable, targets. Less so is Gottfried Reinhardt’s wife, Silvia, included in Picture, it would seem, simply for the rococo non sequiturs she provides. Ross writes of Silvia’s visit to the Red Badge set: “‘We are in a constant state of osmosis,’ Mrs. Reinhardt said, paying no attention to Reinhardt’s agitation. ‘Osmosis has been going on for a very long time. A liquid of a lesser density flowing towards a liquid of a greater density through a thin membrane.’ She uttered a shrill, hopeless laugh and gave a hitch to her Army suntans.”

Gottfried, son of the eminent theater director Max, is perpetually agitated, especially after Huston leaves California, following the second of four disastrous preview screenings of Red Badge, to start his next film. Largely incommunicado, Huston is in what was then called the Belgian Congo, shooting The African Queen—an experience that led to Peter Viertel’s roman à clef White Hunter, Black Heart (1953), which presents a much less flattering portrait of the filmmaker than Picture. Ross, already a friend of Huston’s by the time she arrived in California to do her Red Badge reporting, lionizes him. Huston is charming (addressing his interlocutors as “kid” or “amigo”), witty, unruffled, bigger than life, inseparable from the magnificence of his films. “In appearance, in gestures, in manner of speech, in the selection of the people and objects he surrounded himself with, and in the way he composed them into individual ‘shots’ . . . and then arranged his shots into dramatic sequence, he was simply the raw material of his own art; that is, the man whose personality left its imprint, unmistakably, on what had come to be known as a Huston picture,” Ross writes early on.

That’s a bit high-flown, but Huston—at least as Ross presents him—is good company. He’s also, it turns out, clairvoyant. He doesn’t share an assistant’s anxiety about the threat of TV to the movie industry: “We’ll just make pictures and release them on television, that’s all. The hell with television.” Perversely distorted, that innocuous sentiment could be seen as a forerunner to the odious term “platform agnosticism.” What would a twenty-first-century version of Picture look like, read like? It could have only one title: Content.

Melissa Anderson is the film editor of 4Columns.