IN AN AFTERWORD WRITTEN to accompany the 1990 reissue of her second novel, 1952’s sapphic paragon The Price of Salt, Patricia Highsmith insisted, “I like to avoid labels,” taking umbrage even at being called a suspense writer. The declaration functioned somewhat as a misdirection, deployed to explain why she published the book pseudonymously (as Claire Morgan), though not why she refused until almost forty years later to publicly acknowledge—and thus out herself—that she was the author of this swoony tale of same-sex romance: “If I were to write a novel about a lesbian relationship, would I then be labelled a lesbian-book writer? That was a possibility, even though I might never be inspired to write another such book in my life. So I decided to offer the book under another name.”

What Highsmith, who ranks as perhaps the mid-twentieth century’s most successful serial seducer of women, does not admit is that this fake name ensured that her career wouldn’t be derailed by societal (or, more specifically, the literary establishment’s) abhorrence of lavender life. The Price of Salt, after all, was published the same year that the American Psychiatric Association labeled homosexuality a “sociopathic personality disturbance.” Other types of “personality disturbances”—like those that roiled inside both Bruno from Strangers on a Train and Tom Ripley, two of American literature’s most enduring murderous men—were exactly what animated her oeuvre, consisting of more than thirty books issued over five decades.

The publication of Patricia Highsmith: Her Diaries and Notebooks, 1941–1995, released in part to commemorate the centennial of Highsmith’s birth in 1921 (she died in 1995, at the age of seventy-four), demands another label for the woman who so despised categorization. This thousand-page-plus volume reveals her to be an assiduous chronicler: not only of her chaotic affective life—in particular the dyke drama that she, fond of triangulating, usually instigated—but also of her writing process. The volume, edited by Anna von Planta, Highsmith’s editor from 1984 until her death, represents only a fraction of the fifty-six thick journals—eighteen diaries, devoted to recording her personal experiences, and thirty-eight notebooks, which, von Planta explains, were “workbooks” for the writer to, among other activities, sketch out ideas for potential short stories and novels—that ran to some eight thousand pages.

“As in any self-portrait, the person we encounter in the diaries and notebooks is of course not necessarily the ‘real’ Pat, but instead the person she considered—or wanted—herself to be. . . . Our intention in sharing these entries is to let readers discover, in the author’s own words, how Patricia Highsmith became Patricia Highsmith,” von Planta notes in the foreword. In her peppery 2009 biography of the writer, The Talented Miss Highsmith, Joan Schenkar—who died in the spring of 2021 and who, for the Diaries and Notebooks, provides an afterword titled “Pat Highsmith’s After-School Education: The International Daisy Chain,” a helpful summing up of the subject’s lez circle, whether lovers, friends, or something in between—recasts von Planta’s notion with more dramatic flair and admiration: “Her pitiless self-exposures in her notebooks and diaries . . . have preserved for us what is probably the longest perp walk in American literary history.” Schenkar continues: “She told what she knew . . . and she told it in a far more direct and forthcoming voice than the low, flat, compellingly psychotic murmur she tended to use for her fictions. She makes it easy for us to be ravished by her romances, sullied by her prejudices, shocked by her crimes of the heart, appalled by the corrosive expression of her hatreds. But her long testimony in the witness stand of her notebooks, and in the jury box and judge’s chair of her diaries, is far more revealing than anything anyone else has written or said about her.” (Also revealing: the fact that Highsmith often wrote her diary entries retrospectively and backdated them. She fudged the chronology, Schenkar says, “to give order to her life, altering the record of her life and the purport of her writing by doing so.”)

That “anything anyone else has written or said about her” might include Andrew Wilson’s dutiful, occasionally dull 2003 biography Beautiful Shadow; ex-girlfriend Marijane Meaker’s unsparing memoir Highsmith: A Romance of the 1950s from the same year; maybe even Schenkar’s own lively study, which audaciously forgoes chronology to organize Highsmith’s life by themes, or, more accurately, obsessions. (All of these books are acknowledged by von Planta in the Diaries and Notebooks; rightly, no mention is made of Richard Bradford’s execrable biography Devils, Lusts and Strange Desires, published early in 2021 and gloriously demolished by Highsmith savant Terry Castle in the London Review of Books.)

These three valuable chronicles provide both shrewd assessments (Schenkar’s observation that “no writer has ever savored the pains or suffered the pleasures of repetition more than she did”) and unflattering disclosures (Wilson’s reporting that it was Highsmith’s agent, not the writer herself, who ultimately insisted on The Price of Salt’s happy ending; Meaker’s recounting of a horrific 1992 visit by a soused Highsmith, who erupted into anti-Semitic and racist screeds throughout her short stay). But nothing, as Schenkar suggested, in those volumes compares with the galvanic thrill of reading Highsmith’s raw first-person accounts, of following the writer as she tries to make sense of her self over the course of half a century. None of those books, no matter how much they have historicized and expanded our understanding of Highsmith, contains a passage as evocative as this entry from her 1946 journal: “Sometimes writing is like being seen crying at a friend’s funeral.”

In fact, the confessions, insights, despair, and pique in Highsmith’s journals match, if not surpass, those in the diaries of Susan Sontag—who, twelve years Highsmith’s junior, was her near equal in terms of prodigious output and shambolic lesbian love life. The publication history of Sontagiana, though, is the inverse of the Highsmith books, since the release of the younger writer’s diaries preceded by several years the authoritative third-person account. The agonized entries in Reborn and As Consciousness Is Harnessed to Flesh, published in 2008 and 2012 respectively, were expounded upon at length by Benjamin Moser in his superb 2019 biography, Sontag: Her Life and Work, which astutely placed the anguish in her personal life within the context of the triumphs of her public one. Along with Sontag’s, the Highsmith journals constitute an indispensable record of a highly renowned writer negotiating—rarely escaping, often chafing against—the restraints of the closet in the decades just before and after the LGBTQ-liberation movement.

Von Planta begins the book with Highsmith’s first diary, begun on January 6, 1941, when the writer—then a junior at Barnard and living, miserably, with her mother and stepfather in a one-bedroom apartment at 48 Grove Street in Greenwich Village—is less than two weeks away from turning twenty. “Many people are familiar with the somber, caustic version of Pat,” von Planta says, “and this volume will be their first encounter with the author as a cheerful young woman with an optimistic, ambitious eye on her future.” Her twenties were also marked by her most prolific journaling; the first of the five sections of the Diaries and Notebooks, spanning 1941 to 1950, the year she published Strangers on a Train, her debut novel, account for half the book’s pages.

The alacrity on display in this meaty, opening segment of the Diaries and Notebooks is certainly surprising. Highsmith’s fondness for exclamation marks rivals a zoomer’s: “I’m diving into theater! I will be good, good, good!!!” (The diary entries through 1952 have another remarkable aspect: glossophile Highsmith composed them in up to five different languages. The workbooks, in contrast, were written almost entirely in English.) The summer before her senior college year, she is certain of the triumphs that await her: “I have a great destiny before me—a world of pleasures and accomplishments, beauty and love.” Another touching entry from ’41 finds Highsmith avowing that drink and creativity are incompatible: “I can think of no great writers or thinkers or inventors who were notorious sots. Poe, of course. But the rosy haze of drunkenness is singularly unproductive—seemingly fertile at first—but put your ideas into concrete practice and they vanish like a soap bubble.”

Soon enough, though, ruinous tippling would become a daily practice. In 1947, she admitted, “I drink whiskey to stupefy myself, and regret what it does to my body—fat cells, deterioration of the brain, above all indulgence in a dependence upon materiality when what keeps me awake is a spiritual intangible.” She regularly recorded the oceanic amount of spirits she imbibed, whether at home or at one of her favorite Manhattan lavender haunts: the Jumble Shop, the Gold Rail Bar, the Nucleus Club, Spivy’s Roof. The resurrection of these little-known, charmingly monikered queer NYC boîtes provides its own ancillary pleasures; Highsmith’s detailing of her evenings out serves as a kind of stealth history of midcentury homo nightlife.

By middle age, Highsmith was much less introspective about her addiction than she had been as a twentysomething. Castle, in that recent LRB essay, piquantly describes the ravages of the writer’s colossal consumption: “Highsmith’s alcoholism blighted her life and eventually transformed her—not entirely figuratively—into a Dorian Gray–style lesbian fright-bag. Heartbreakingly attractive in her youth . . . she looked like a sullen gargoyle by the time she died: rubbery, bloodshot, wrinkled to the point of cave-in, a calamitous experiment in DIY self-pickling.”

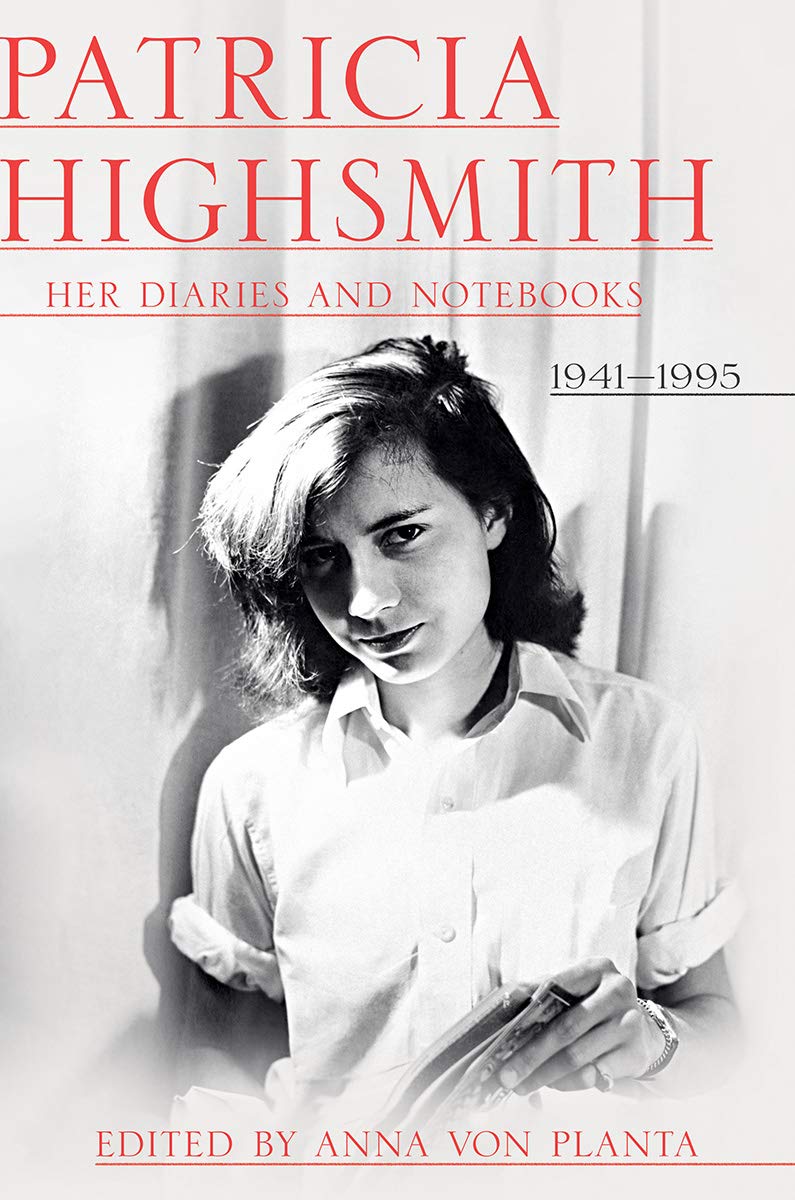

The five photographs that accompany each section of the Diaries and Notebooks starkly bear out Castle’s assessment, functioning as a flip-book of dissipation. Preceding the pages devoted to 1941–1950 is the same striking image that greets us on the cover: a twenty-one-year-old Highsmith, shortly after graduating from Barnard, staring directly at the camera, a swoop of bangs covering one eye, both sleeves of her oxford rolled up high. She exudes an overwhelmingly seductive soft-butch duende, a charisma that ensorcelled many of the women on her ranked, busily annotated “Lovers Chart” from 1945.

Despite her profound commitment to sapphistry—“Without [women] I would and could do nothing! Every move I make on earth is in some way for women. I adore them!” she gushed in 1947—Highsmith was at least twice involved in confounding relationships with men. One of these fellows was the German photographer Rolf Tietgens, who snapped that fetching Highsmith photo described above, and who, like her, was gay. They met in the summer of 1942, in the manner Highsmith usually preferred: through someone else with whom she was, at the very least, already heavily emotionally involved, in this instance Ruth Bernhard, another German expat photographer. Tietgens and Highsmith’s attempts at physical intimacy were invariably defined by extreme ambivalence: “He was pleasantly shy, wanted to do everything, but also didn’t want it. Am happy he didn’t do anything, though, otherwise I’d be disgusted in the morning,” she wrote in September ’42. An entry composed the day before this thwarted attempt to sleep together expressed the obvious: “Men are not magic to me that is all.”

After World War II, Highsmith’s dabbling in heterosexuality included a miserable relationship with the English novelist Marc Brandel (“When he touches me, anywhere, I cannot bear it”), whom she met in 1948 at Yaddo (where she finished a first draft of Strangers on a Train) and who would be her on-again, off-again fiancé for the next year or so. In a pleasingly perverse, Highsmithian irony, her wretched romance with Brandel led, in a roundabout way, to The Price of Salt, among literature’s greatest paeans to tribadism. During their courtship, Highsmith tried to “cure” or at least understand her homosexuality, a quest that impelled her to seek out psychoanalysis. To afford her therapy, she took a part-time job working in the toy department of Bloomingdale’s during the Christmas season of 1948. One morning she sells a doll to a soigné blond, a New Jersey matron named Mrs. E. R. Senn, who made her feel, as she wrote in that 1990 afterword, “odd and swimmy in the head, near to fainting, yet at the same time uplifted, as if I had seen a vision.” Later that night, Highsmith produced in two hours a complete synopsis of what would become her great lesbian romance, centering around an ingenuous shopgirl named Therese and the older, more sophisticated Carol.

Writing it proved to be both a euphoric and arduous experience. “How well it all goes,” Highsmith noted in December 1949. “How grateful I am at last not . . . to spoil my best thematic material by transposing it to a false male-female relationship!” Six months later, she was in agony: “This is such a painful novel I am doing. I am recording my own birth.” No one, including Highsmith, could have predicted The Price of Salt’s enormous success; after its paperback release in 1953, it would eventually sell more than a million copies. The mass-market publisher Avon offered her a generous advance for another sapphic love story. This project, with the working title The Breakup, was ultimately abandoned, as was a sort of sequel to The Price of Salt.

The sustained bliss that The Price of Salt’s ending seems to promise Carol and Therese would largely evade its author. “The greatest and most honest book about homosexuals will be written about people who are horribly unsuited and who yet stay together,” Highsmith recorded in her journal in 1954. Her Diaries and Notebooks might just be that book. Highsmith details at length her incessantly fractious four-year relationship in the 1950s with sociologist Ellen Hill, who could not abide the sound of her lover’s typing, and another doomed four-year romance, in the 1960s, with a married Londoner given the pseudonym here of Caroline Besterman.

After the calamitous end of her affair with Besterman, something curdles in Highsmith. In 1975, the zealous lady-lover published a volume devoted to lady-hate: Little Tales of Misogyny, perhaps an unsurprising project from someone who, twelve years earlier, jotted in her journal, “Women are, alas, showing themselves more infantile and incapable than ever in whining about their lot in 1963.” Although romantically and sexually active well into her senescence, she writes encomiums for her cats—exultant poems once reserved for girlfriends. As she ages, she grows more bilious, her political views more unhinged.

But there is always work—“my best opiate, really my only one,” she called her near-daily practice of writing five to eight pages. And almost every journal entry she composed throughout the decades reflected the reasons why she found this personal record-keeping so essential: “Now I know why I keep a diary. I am not at peace until I continue the thread into the present. I am interested in analyzing myself, in trying to discover the reasons why I do such & such. I cannot do this without dropping dried peas behind me to help me retrace my course, to point a straight line in the darkness.” She wrote that in 1949, the year before a book would be published with her name on it. Before she was a suspense writer, before she was a “lesbian-book writer,” when she was just—as she always would be—a furiously disciplined writer.

Melissa Anderson is the film editor of 4Columns. Her monograph on David Lynch’s Inland Empire is now available from Fireflies Press as part of its Decadent Editions series.