EVEN WHEN THEY’RE WELL WRITTEN, most fictional sex scenes are either porny or icky. Consider Updike’s lyrical depictions of the act. They are not only unsexy, they are often, in their strangeness and precision, a bit gross. (A line from Couples: “Sun and spittle set a cloudy froth on her pubic hair.”)

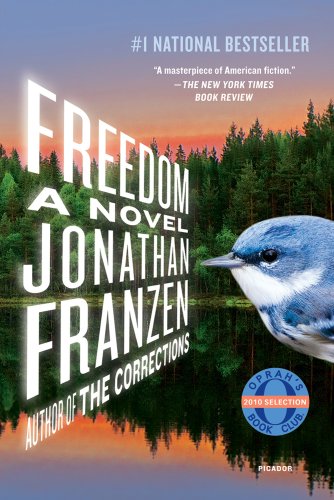

That’s why I admire Jonathan Franzen’s sex scenes so much. Franzen has managed again and again to pull off what so few writers can—to write explicitly about sex in a way that is stylish and mostly non-cringey without resembling the stuff of Penthouse letters. One of his best descriptions of sex takes place when Freedom’s middle-aged and long-married Walter Berglund finally gets together with his lissome young assistant. Lalitha, Walter thinks,

needed to ride him, she needed to be crushed underneath him, she needed to have her legs on his shoulders, she needed to do the Downward Dog and be whammed from behind, she needed bending over the bed, she needed her face pressed against the wall, she needed her legs wrapped around him and her head thrown back and her very round breasts flying every which way. It all seemed intensely meaningful to her, she was a bottomless well of anguished noise, and he was up for all of it. In good cardiovascular shape, thrilled by her extravagance, attuned to her wishes, and extremely fond of her. And yet it wasn’t quite personal, and he couldn’t find his way to orgasm. And this was very odd, an entirely new and unanticipated problem, due in part, perhaps, to his unfamiliarity with condoms, and to how unbelievably wet she was. How many times, in the last two years, had he brought himself off to the thought of his assistant, each time in a matter of minutes? A hundred times. His problem now was obviously psychological.

This, to me, is a near-perfect sex scene. Franzen betrays no fear of the explicit—he doesn’t shrink from telling us that Lalitha was wet. The depiction is also extremely visual. And it feels of the moment; it captures the way someone alive right now would think. It’s also elegant, written with the kind of verve and wit and sense of fun that so often go out the window when novelists start writing about sex. Finally, it’s not gratuitous description, a writer showing off his ability to describe. It’s interesting not because it’s about sex: It’s an interesting moment that happens to be rooted in sex.

Good fictional sex scenes are so often about bad sex. In another passage from Freedom, Walter’s son Joey is finally getting together with a young woman he has been lusting after for years:

As she humped his bare leg through her underpants, grunting a little with every thrust, he felt himself flying out centrifugally, a satellite breaking free of gravity, mentally farther and father away from the woman whose tongue was in his mouth and whose gratifyingly nontrivial tits were mashed into his chest. She fooled around more brutally, less pliantly, than Connie did—that was part of it. But he also couldn’t see her face in the dark, and when he couldn’t see it he had only the memory, the idea, of its beauty. He kept telling himself that he was finally getting Jenna, that this was Jenna, Jenna, Jenna. But in the absence of visual confirmation all he had in his arms was a random sweaty attacking female.

“Can we turn a light on?” he said.

Another thing I like about Franzen’s sex scenes is that they are tonally in keeping with the non-sex-scene parts of his books. So many comic sex scenes hit the same note over and over again—the comedy is in how bad or embarrassing our character’s performance is. The self-deprecation shtick becomes a kind of cliché (as the literary critic Elaine Blair has written in the New York Review of Books). But Franzen’s sex scenes don’t rely on a single vein of humor; he manages to bring to his fictional coitus a more emotionally complex and truer kind of comedy that stems organically from the characters’ overall relationships, while remaining alive to the particularity and peculiarity of sex.

Adelle Waldman is the author of The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P. (Henry Holt, 2013).