In a country whose literary heritage includes the likes of Gone with the Wind and Atlas Shrugged, it should come as no surprise that the most politically influential novel in America during the past half century is terrible. But the terror in this case is literal, too: neo-Nazi leader William Pierce’s The Turner Diaries has inspired multiple generations of white supremacist terrorists since its publication in 1978. Framed as the memoirs of Earl Turner, engineer and bomber, the Diaries tracks the exploits of the Organization, a revolutionary group devoted to the violent overthrow of the federal government and the global extermination of all people of color. As in traditional racist demonology, nonwhites are depicted as beasts and Jews as sinister manipulators. But the book’s rage is also directed at another target: the federal government, referred to throughout as “the System,” and despised for its promotion of racial intercourse. After successfully bombing FBI headquarters, Turner is inducted into the Order, the secret circle at the head of the Organization; thereafter he is privy to a cockpit view of the secession, ethnic cleansing, mass lynchings, and atomic warfare triggered by the Order to empower itself as it shatters the System’s foundations.

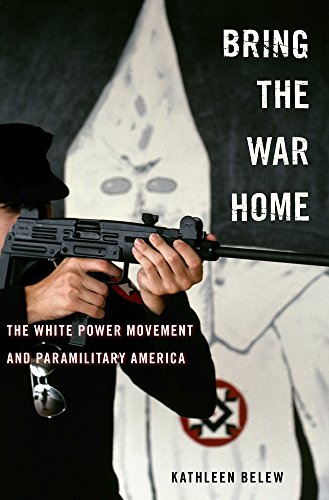

By 1998, the Diaries had sold half a million copies; it was, and remains, a best seller with teeth. In the introduction to Bring the War Home, her history of the white power movement, Kathleen Belew describes the book as “essential in binding the movement together.” The Diaries, she writes, “provided a blueprint for action, tracing the structure of leaderless resistance and modeling, in fiction, the guerrilla tactics of assassination and bombing that activists would embrace for the next two decades”; it “popped up over and over again in the hands of key movement actors, particularly in moments of violence.” The Order, the primary white power terrorist group of the 1980s, whose actions are at the center of Belew’s book, borrowed its name and operations (counterfeiting, bombing) from the Diaries. The bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, identified by Belew as the movement’s most significant act to date, a “culmination of two decades of white power organizing,” was carried out by Timothy McVeigh, a Gulf War veteran who sold copies of The Turner Diaries at gun shows.

Belew traces the origins of the contemporary white power movement to the aftermath of the Vietnam War. Defeated abroad, racist white servicemen returned to a nation altered by the civil rights struggle and cultural liberalism, and shaken by race riots and the Black Power movement. The twin failures of the state to uphold American supremacy in Indochina and white supremacy in the apartheid South crystallized in the image of the veteran betrayed by the system and aching for revenge. What Belew somewhat euphemistically calls “feelings of defeat, emasculation, and betrayal after the Vietnam War” were central to the movement’s emotional appeal: The American government, last remaining hope of global white supremacy since 1945, had been decisively defeated in battle by Asian Communists. In order to keep the cherished image of white invincibility from being irrevocably dishonored, drastic action would have to be taken, not least of all against the state itself, which had betrayed its racial mandate. Many leading figures of the white power movement were veterans, and all drew from the same myth of the soldier unbacked by the state in his war against racial inferiors. Robert Jay Mathews, who founded the Order, was so enraged upon learning of Lieutenant William Calley’s prosecution for the My Lai massacre that he canceled his plans to enlist. Animated by the narrative of central government as race traitor, Mathews and others like him managed to align scattered fringe groups into a coherent and tenacious movement. Its foundations laid in the 1970s, the white power movement proliferated in relative obscurity during the 1980s before its acts burst into public consciousness with the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995; its legacy persists to the present in the fascist militias that convened last summer at Charlottesville.

Belew focuses especially on Louis Beam, a working-class white veteran from Texas with a flair for oratory, whose post-traumatic stress and sense of national betrayal bled into his essays and his violent threats alike. After returning from the war in the late 1960s, Beam fell in and out of various far-right groups before founding the Texas branch of David Duke’s Knights of the Ku Klux Klan. He purchased fifty acres of swampland and constructed Camp Puller, “a Vietnam War–style training facility designed to turn Klansmen into soldiers.” When, in the late ’70s and early ’80s, white fishermen in Texas, losing out in competition with newly arrived South Vietnamese immigrants, sought to drive the “gooks” out by any means necessary, they turned to Beam’s militia for aid. (The fact that many of the immigrants were anti-Communist soldiers failed to register with any of the whites involved, and with Beam least of all: For him, the Vietnamese were the enemy without exception.) As tensions escalated, the impending pogrom was averted only by Gabrielle McDonald, a federal judge who issued, in 1982, an injunction disbanding the militia.

The ruling marked a turning point in the nascent movement’s history. Soon after, Beam decamped for the Aryan Nations compound in Idaho, where in 1983 he and the rest of Mathews’s newly founded Order declared, for the first time, a violent revolution against the federal government. Over the next few years, the Order would counterfeit currency and rob sex shops, banks, and armored cars (once netting $3.6 million in a single raid); the proceeds funded movement groups such as Pierce’s National Alliance, and the Order’s own violent actions, which culminated in the assassination of Denver radio talk show host Alan Berg in 1984.

Though the federal prosecution for Berg’s murder would cripple the Order, the decentralized structure of the larger movement enabled it to survive. The Cold War bequeathed tactics in addition to symbols: Beam’s theory of “leaderless resistance,” in which white power soldiers cooperated in small cells of five or fewer, guided not by a central hierarchy but rather activated by general principles disseminated through movement propaganda, was adapted from the Communist underground. “Leaderless resistance” insulated the movement from state infiltration and shielded its chief ideologues and organizers from state prosecution; further-more, it was well suited to a movement whose constituent groups were both scattered across the country and notoriously fractious. The prevailing thesis has been that white power terrorist attacks are isolated “lone wolf” incidents unrelated to one another. Though McVeigh, following his arrest, presented himself as someone who had acted alone, Belew’s research demonstrates otherwise. He may have received no orders from above, but no such orders were necessary. The Murrah Federal Building had been a longtime target of one of the movement’s groups, an armed religious sect in close proximity—geographical and ideological—to the Klan chapter McVeigh consorted with and to Elohim City, a white separatist compound.

Belew is particularly adept at tracing the myriad personal, spatial, temporal, and operational links that constitute an essentially decentralized movement. As she shows, local hate groups, safe havens like Elohim City, and sites of proselytizing and recruitment such as gun shows are all subtly connected, forming a worldwide web that encompasses, of course, the web itself. Gamergaters, 4chan weeaboos, and the alt-right are only the latest entries in a long tradition of white power online: Belew describes how, in the ’80s, the Order invested much of the proceeds from its criminal activities, including a multimillion-dollar armored car heist, into buying personal computers and setting up an encrypted online forum (Liberty Net) to facilitate secrecy and promote coordination.

The book’s seventh and best chapter is a lucid exposition of the devotion paid to women as wives, mothers, and martyrs of the movement. White power submitted itself to a blinding cult of faith and family centered on the female body: Belew describes a 1985 Aryan Nations illustration, drawn by a woman, of “a blond and blue-eyed Mary, Joseph, and infant Jesus surrounded by white-robed Klansmen on one side of the manger and uniformed neo-Nazis on the other.” She recognizes the consonance of such visions of femininity with contemporary arguments about the place of women in American society and, better still, highlights the historical link between sexual and racial hierarchy: “American white supremacy had long depended upon the policing of white women’s bodies. In order to propagate a white race, white women had to bear white children.”

Had such penetrating statements regarding the relationship of women to whiteness been matched in other chapters by assessments of the relationship of whiteness to the world, Bring the War Home would have been more than necessary; it would have been definitive. Yet Belew’s social analysis and historical frame are ultimately too narrow to explain the movement’s reach and persistence. Though she places the Vietnam War at the center of her story, she fails to spell out the ties between domestic white supremacy and US imperialism. Near the end of the book, Belew posits that the existence of the white power movement indicates that racism was not abolished after the civil rights era, that right-wing threats to a liberal society have yet to abate. The road to progress, it seems, can still be blocked off by a rented U-Haul bulging with ammonium nitrate.

But to accept the white power movement’s own dichotomy between the American government and a violent revolutionary movement committed to overthrowing that government—to oppose the System and the Order too absolutely—is to overlook the obvious parallels between the two. For all its anti-statist rhetoric, white power has imitated American militarism with great fidelity: As Belew observes, “the Order’s strategy came entirely from U.S. Army training manuals and books about U.S. military strategy.” Then and now, the white power movement has had significant success in recruiting active-duty soldiers to its cause. Belew notes this paradox, but her inability to fully recognize its source speaks to the limitations of her history.

In 1980, not long before the founding of the Order, James Baldwin made the true and simple claim that “white is a metaphor for power.” All the same, “white power” could only emerge as a revolutionary slogan once some measure of dissonance had crept between its terms. White is a metaphor for power, but the face of power is no longer exclusively white, and in fact has been growing less white by the day for many decades. The subjects of Belew’s book are marginal but not anomalous; you could call them first responders. Among whites, it is no longer a fringe that finds itself ranting against a system rigged, still quite substantially, in their favor. Angry fantasies of restoration prevail; the ludicrous, redundant evil of white American power sprawls, naked and spread-eagle, before a planet recoiling at its capacity to ruin everything and its inability to rule anything, itself least of all. What does the Trump administration signify, if not that the Order is the System, and that both are past redemption? The Turner Diaries concludes with its protagonist preparing to fly a nuclear bomb into the Pentagon. White power was always going to end in suicide, with a schizoid weapon in revolt against its master. It’s the collateral damage that remains an open question—or at least it would be nice to think so.

Frank Guan is a writer in New York.