Frank Guan

WHEN, LATE IN JONATHAN FRANZEN’S NEW NOVEL CROSSROADS, a woman, reuniting with an ex-flame after thirty-one years, notes “recent Mailer, recent Updike” on his shelves, the shock of the old is both soft and profound. It’s 1972; the dinosaurs still stamp and bellow. They can’t imagine how much they will lose.

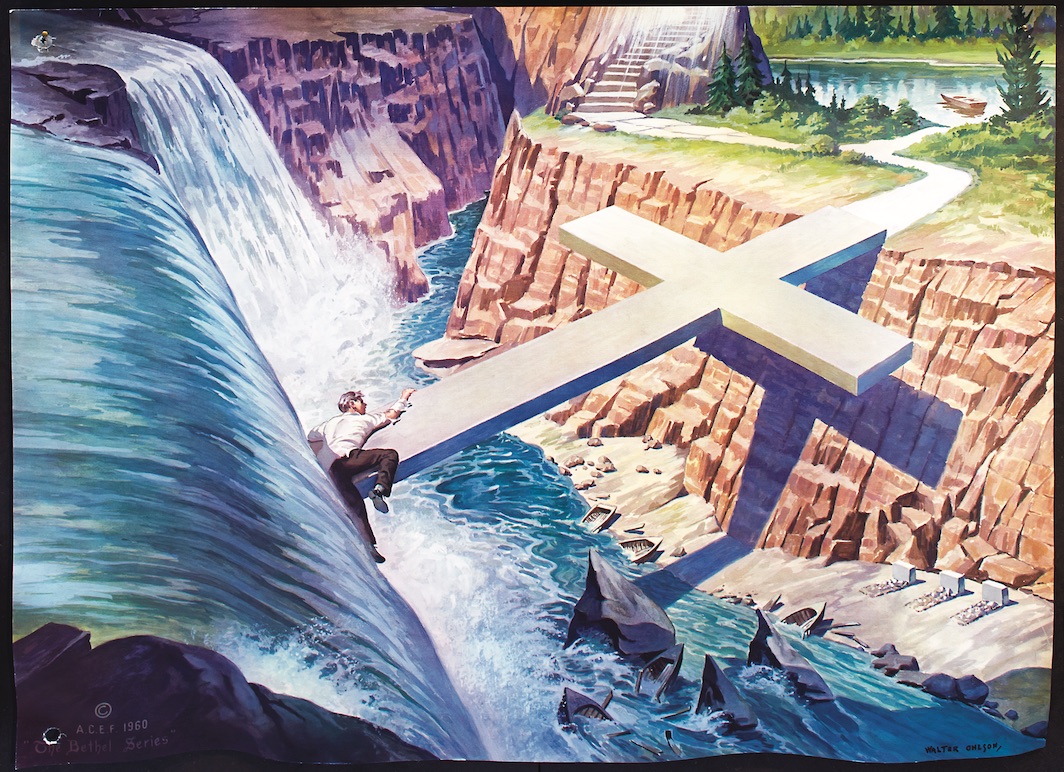

TWO FIGURES OVERLOOK A SACRED RIVER: both qualify as students, yet one is more experienced by far. He attempts to bridge the difference with a lesson. Pointing to the wastelands on the right bank, he defines it as sunyata, the void. Then, turning, points at the city opposite. An enormous maze of temples and houses, the dwellings of deities and castes: that is maya, illusion. “Do you know what our task is?” A test. “Our task is to live somewhere in between.” We have two versions of the scene, but in each case the younger student is described as “terrified.”

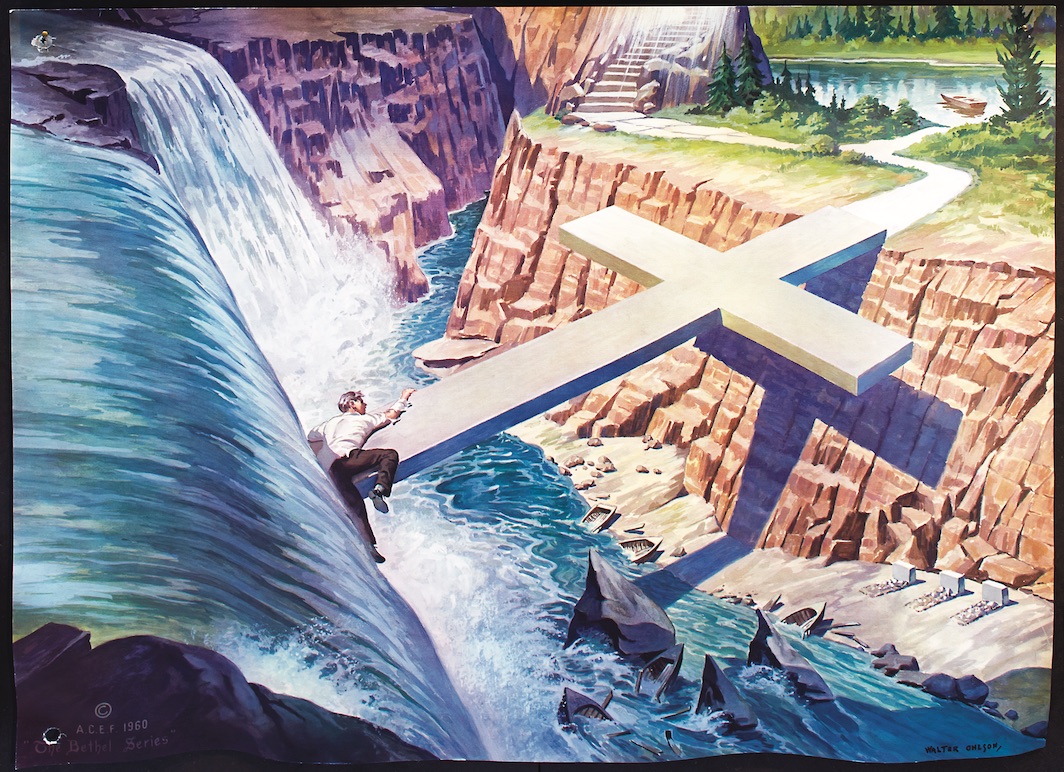

Bhaskar Sunkara’s Socialist Manifesto begins by entering an imaginary world. It’s 2018 and “you” are a die-hard fan of Jon Bon Jovi, “the most popular and critically acclaimed musician of this era.” So devoted are you to the singer-songwriter that you’ve found work at the pasta sauce factory his father owns in New Jersey. The job isn’t great, but it’s better than nothing. After a year, your wages rise from $15 an hour to $17, a 13 percent increase that fails to match your recent 25 percent increase in productivity; meanwhile your colleague Debra, who’s been working there for three

The first piece in The Souls of Yellow Folk, the collection of Wesley Yang’s journalism, goes in with a bang. “The Face of Seung-Hui Cho,” Yang’s 2008 essay on the mass shooter of Virginia Tech, is a remarkable attempt to trace the author’s kinship with a young man who, one year earlier, had killed thirty-two people and then killed himself. Outlining Cho’s abysmal, toxified, embittered half-life, Yang describes his own as well. Raised American, both have inherited an unfortunate legacy: In the home of the brave, their meek yellowish faces have disqualified them from all human consideration. Their efforts at

If there was one book impossible to escape during the eternal election of 2016, it was J. D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy. The Ohio native’s “memoir of a family and culture in crisis,” which detailed his dismal childhood with a substance-abusing single mother and his ascension, through hard work and education, into the ranks of the coastal elite, received rapturous praise upon its publication. Liberal and conservative commentators alike seized on its narrative and setting as a key to the candidacy and election of Donald Trump. In Vance, they discovered a trustworthy local interpreter from Trump Country—one willing to confirm that

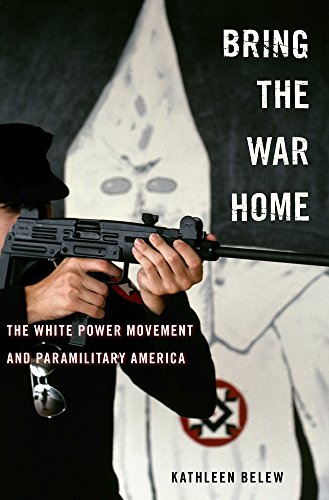

In a country whose literary heritage includes the likes of Gone with the Wind and Atlas Shrugged, it should come as no surprise that the most politically influential novel in America during the past half century is terrible. But the terror in this case is literal, too: neo-Nazi leader William Pierce’s The Turner Diaries has inspired multiple generations of white supremacist terrorists since its publication in 1978. Framed as the memoirs of Earl Turner, engineer and bomber, the Diaries tracks the exploits of the Organization, a revolutionary group devoted to the violent overthrow of the federal government and the global

The closest thing to a consensus explanation for Trump’s election that has emerged in the wake of November 2016 is the notion that “the Left,” in relying on appeals to “identity politics” rather than to economic class, contributed to the GOP victory by provoking a backlash among white men and workers. In Mark Lilla’s The Once and Future Liberal: After Identity Politics and Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff’s The Coddling of the American Mind, centrist liberal academics showcased their predilection for battling the Right by punching left. Scornfully arraigning the campus thought police and mobs of online paladins prowling their