The first piece in The Souls of Yellow Folk, the collection of Wesley Yang’s journalism, goes in with a bang. “The Face of Seung-Hui Cho,” Yang’s 2008 essay on the mass shooter of Virginia Tech, is a remarkable attempt to trace the author’s kinship with a young man who, one year earlier, had killed thirty-two people and then killed himself. Outlining Cho’s abysmal, toxified, embittered half-life, Yang describes his own as well. Raised American, both have inherited an unfortunate legacy: In the home of the brave, their meek yellowish faces have disqualified them from all human consideration. Their efforts at creative writing capsize; their striving to stake out a definite social position is doomed; their chances of scoring approach zero. They have nothing to live for, and though Yang is no murderer, he understands clearly how Cho, over the course of being thoroughly negated by “a system of social competition that renders some people absolutely immiserated while others grow obscenely rich,” might take it into his head to fatally assault “a world of individually determined fortunes, of winners and losers in the marketplace of status, cash, and expression.”

Like his subject, Yang makes himself known by an act of radical, desperate self-exposure. What he possesses that Cho doesn’t is elegance and distinction of expression. He channels the extremity of his subject matter into a marvelous style, a fluency and clarity that refuse to renounce their ruinous origins. The reflexive desolation of his signature tone stands out: Yang’s language is reliably magnetic during passages in which he broods over his defeats. Employing this technique to great effect in “Paper Tigers,” his National Magazine Award–winning cover story for New York magazine in 2011, Yang describes a failed bid for artistic standing in his twenties:

No one had any reason to think I was anything or anyone. And yet I felt entitled to demand this recognition. I knew this was wrong and impermissible; therefore I had to double down on it. The world brings low such people. It brought me low. I haven’t had health insurance in ten years. I didn’t earn more than $12,000 for eight consecutive years. I went three years in the prime of my adulthood without touching a woman. I did not produce a masterpiece.

The tensile strength of such a passage suggests a wild resilience, a capacity to rekindle lasting fires from the ashes of dejection. Here, as in “The Face of Seung-Hui Cho,” Yang writes from the outsider’s vantage. But his estrangement has been doubled: The author of “Paper Tigers” recounts feeling alienated, “both from Asian culture (which, in my hometown, was barely visible) and the manners and mores of my white peers. . . . An education spent dutifully acquiring credentials through relentless drilling seemed to me an obscenity. So did adopting the manipulative cheeriness that seemed to secure the popularity of white Americans.” In spite of having crashed and burned in his initial attempt to become “an aristocrat of the spirit,” he vows to press on in his lonely quest “to be an individual.”

The other focus in “Paper Tigers” is the “Bamboo Ceiling,” the subtle discrimination barring East Asians in America from positions of authority in the educated workforce. Interviewing a plethora of East Asian businessmen, academics, pickup artists, and aspiring writers, Yang uncovers a common experience of being treated as, if not quite second-class, secondary nonetheless. He advances the notion that the only way for East Asians to overcome the prejudices applied to them by society is to defy them. “Let me summarize my feelings toward Asian values: Fuck filial piety. Fuck grade-grubbing. Fuck Ivy League mania. Fuck deference to authority. Fuck humility and hard work. Fuck harmonious relations. Fuck sacrificing for the future. Fuck earnest, striving middle-class servility.” Rather than confirming the view of them as deferent, reserved, unsexed, soft, overridden, East Asians must be clamorous, expressive, seducing, harsh, selfish to the point of monstrosity. “In lieu of loving the world twice as hard,” Yang declares, “I care, in the end, about expressing my obdurate singularity at any cost. . . . I’m fine. It’s the rest of you who have a problem. Fuck all y’all.”

In “The Face of Seung-Hui Cho” Yang posited himself and Cho as separate but related instances of a general phenomenon of social dispossession: They, and countless others, not necessarily East Asian American men, shared in the experience of late-capitalist Everyman, tortured by the images and pitches of a sexual marketplace where they could find no purchase. Moving, in “Paper Tigers,” from descriptions of a universal misery toward prescriptions directed at a specific demographic, Yang necessarily risks neglecting dimensions of social experience alien to his own interest. The specific travails of the hyperfetishized East Asian woman are one glaring omission; another is the possibility that, as with other races, white Americans’ deep investments in, and real benefits gained by, discounting East Asians might preclude the sort of unilateral solution to bigotry Yang recommends. Finally, there is the issue of Yang’s own discounting of East Asians. Even leaving aside the fact that these values fail to account for the fullness of East Asia’s culture and society, it seems questionable that an author so vehemently against East Asians as such would be well-equipped to speak for East Asians as a whole.

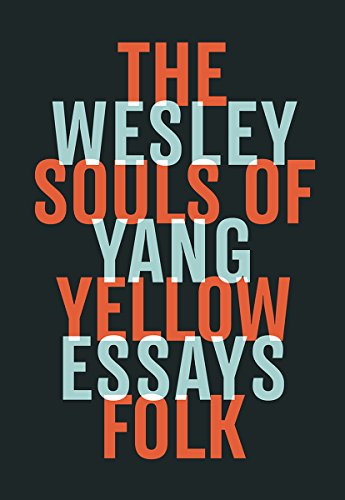

The Souls of Yellow Folk’s comprehensive title suggests a will to rectify these omissions. But besides a fig leaf introduction and a first section comprising “The Face of Seung-Hui Cho,” “Paper Tigers,” and a profile of the chef and author Eddie Huang, the articles collected here, all previously published elsewhere, address the nature of East Asians in America only in passing, and frequently not at all. One of the drawbacks of assembling a book from a haphazard pile of articles is the difficulty of establishing a central theme from the assortment of scattered elements: Yang’s book, a crisply sorted stack of application essays and homework assignments fobbed off as a master’s thesis, is no exception in this regard. Rather than a map of a people, the essays present the author’s individual preoccupations. Profiles, surprisingly gentle given the author’s professed scorn for in-groups of all kinds, of intellectual elites such as the digital prodigy Aaron Swartz and the professors Tony Judt and Francis Fukuyama, are followed by essays on the image of Britney Spears, New York magazine’s Sex Diaries, and a cynical microhistory of pickup artists in a sexual economy where “each player gives what he must and takes what he can.” The catalogue concludes with editorials, one for Harper’s Magazine and two for Tablet, weighing in against the hazards of identity politics: Left-wing campus activists are “charged with authoritarian potential.” Whether or not one believes this charge, it suggests that Yang, the radically self-centered individual, has reformed himself into a grim apostle of radical centrism and its “liberal individualist emphasis on laws and rights.”

In The Souls of Black Folk an unprecedented portrait emerged—one of a full black nation, sorely beleaguered but rich in spirit, undeniably separated from America at large yet determined to equal its strength. Yellow Folk offers nothing nearly so rousing, direct, or coherent. An impressionable reader could easily exit it assuming East Asians will develop souls only through unconditional adherence to white American mores. By asserting the character of his race, W. E. B. Du Bois was also asserting his own individuality. He was, in short, practicing “identity politics.” Yet since Yang takes East Asians, in their unreformed state, to actually be the cowardly conformist automatons whites view them as, his corollary is that individuality may be achieved solely by means of the liberal universalism modeled by himself—and, of course, by Fukuyama, whose notion of “the struggle for recognition” Yang borrows in his introduction.

Fuming against identity politics for Tablet in 2017, Yang describes “a beguiling compound of insight, partial truths, circular reasoning, and dogmatism operating within a self-enclosed system of reference immunized against critique.” Yet much of his own writing exploits a similar logic. How else to describe his unconditional respect for anyone who fancies himself “a teller of hard, impolite truths”? The phrase comes from his 2010 profile of Judt, but applies verbatim to his 2018 profile of Jordan Peterson. When these tenured intellectuals, brandishing their contempt for identity politics as they dissent from the groupthink of unpopular liberal elites, win acclaim from freethinking crowds for their noble speeches, one can rest assured that in both cases, near the shining figure of the white sage, the yellow epigone marks up his words, imagines them his own: Man up! Be individual!

In mainlining these articles, one comes to recognize that the “devastating empathy” referenced in a generous blurb is something else entirely. Aggregation has exposed, as never before, the degree to which Yang leans upon Procrustean reduction to achieve his effects. Yang’s trick, his only trick, is to reduce his subjects to a single axis, that of conformity or nonconformity with power: Since this aspect of our being is at once essential and something we would rather not face fully, such radical reduction makes us feel seen, understood at a deep level. Yet behind the balanced sentences and mots justes Yang’s sensibility cuts itself down to a tiny set of facile precepts. Society and individuals are guided exclusively by mercenary self-interest; it is good to stand against the crowd; one should cease whining about injustice and get with the program. Contradictions between the second and third truisms—what crowd has not a program, what program not a crowd?—are rendered unsolvable by the first, which negates all mediating ideologies. One is left, then, with a tyranny of arbitrary judgment that always seems to favor those who already hold power. It may have taken a decade to achieve it, but perhaps Yang has found his own way to become the kind of timid conformist he holds in such contempt.

Frank Guan is a writer living in New York.