What’s in a name? I ask, though with admittedly far less ardor than Shakespeare’s blushing young lover once asked her Romeo. Nowadays a woman knows that not every rose smells equally sweet—or is uniformly thorny, for that matter—and that the tragic answer to Juliet’s question in our relentlessly desperate times would most likely be: Depends on what you’re worth.

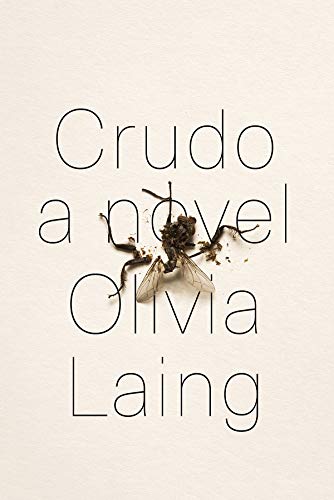

Which is all to point out that there are two couplings in Crudo, British author Olivia Laing’s first novella, a work of autofiction: one romantic, the other nominal and essentially a literary gimmick. Written over seven weeks last summer, Laing’s whirling story spins from her realization that she is in love, perhaps for the first time, with the man she’s marrying: in life, poet Ian Patterson, although he remains unnamed on the page. Laing writes in the first person, in an I she’s wedded to the notorious experimental writer Kathy Acker (1947–97): “Kathy, by which I mean I, was getting married,” she begins, thereafter lacing the 133 pages of the book with forty-six citations appropriated from sources as disparate as @realDonaldTrump and, of course, Acker’s writings, all listed at the end. In frenetic prose that mirrors the velocity of a mind online, Kathy zooms in and out on the intimate details of her rather lovely life—her husband’s freckled backside, the porchetta in rolls they eat on holiday in Italy, their shared love of gardening—while the mad world at large pitches and reels and threatens to capsize in the era of Trump.

Ah, romance! Who wouldn’t like a sweet, sweeping love story right about now? But unfortunately, Kathy isn’t a terribly riveting heroine, proving herself insufferable nearly right out of the starting gate. She mentions four times before the reader reaches page fifty that she’s forty years old, and counts down the days to her wedding as though she’s hearing the tick-tock of a doomsday clock. “Marriage in 5 days, marriage in 4 days.” “It is now 3 days till she gets married.” “Two days to go. 53 hours.” She spends her time scrolling through Twitter and Instagram, or puttering around with her husband, at home or abroad or in their garden. She worries for the world, but doesn’t do much about it. The virtual onslaught of global news and stories and opinions overwhelms her, numbs her, though it hadn’t always. As she writes: “Back in the day she’d done her time in the black bloc, she’d jostled to the front, shoulder to shoulder with the bandana boys, the brick-throwers, but then she’d decided she hated them, that the whole thing was dogmatic and foolish, a game on both sides. Hard to tell now. Depends where you’re standing.” It seems Kathy, as the I of this storm, prefers to stand safely in its middle.

Some distaste for Kathy is likely by design, buffered by occasional self-effacements that let the reader know that she too isn’t altogether happy with who she is. “You’re selfish and rigid and absorbed, you’re like an infant,” she erupts on one occasion. Readers could forgive her for being so self-involved, and perhaps even find a lesson or two in it. After all, there is a grand literary tradition that luxuriates in the privileged perils of married white women. But any compassion for Kathy is utterly undone when Laing minces across the world’s violent political terrain. Some of her responses to the American landscape, for example, hit my ear with the deafening thud of liberal white punting.

On seeing a photograph of Trump staring at an eclipse: “She didn’t like anything about him whatsoever, but she did understand why you might just want to look at the sun eye to eye.” Regarding the fiery debates over painter Dana Schutz’s right to represent the body of Emmett Till: “She didn’t like or dislike the Emmett Till painting, she had strong feelings about what had been done to Emmett Till but as to what a person could or couldn’t paint, no.” Explaining the KKK’s motivations: “They wanted milk and honey, the whole Biblical nine yards, and also the rivers of blood and burning cities, Slave Street up and running again, reanimating those abject bodies. It was like living in a Philip Guston painting, it was that dumb and rotten, that cartoonish.” Disliking Trump; politely referring to the murder of a child as “what had been done to Emmett Till”; describing the lethal dreams of white supremacists as being like a Philip Guston painting: Perhaps this is just British reserve? More likely, this is callous thinking and careless writing.

Which brings me finally to Acker, Laing’s ill-fitting avatar. Wherefore art thou Kathy, narrating the joys and anxieties of domestication, diluting your ink before the grisly horrors of this world? Acker herself was intellectually and sexually feral (“I absolutely love to fuck”), uncompromising, competitive, self-promoting, prolific—and unapologetically possessed of the ambition to be the greatest writer of her generation. She married twice, and had countless lovers. Her devotees would say that she bested William S. Burroughs’s cut-ups, boldly looting other writers’ texts, kidnapping their characters and revamping their words into witty, wicked narratives that brazenly middle-fingered so many of the powers that be. She pillaged Rimbaud, Dickens, Pasolini. In Acker’s books, Don Quixote, a woman, has an abortion; Toulouse-Lautrec fucks a man with a “big red cock.” All her twistings of literary history were acts of insurgence—authorial transgressions offered as a kind of liberation. She compressed author and reader and subject, her chameleonic I taking on all manner of personae, her strapping texts delighting in the destabilizations that followed. Hers is a forceful, almost radioactive body of work, the potency of which hasn’t decayed much since her death.

So what’s Laing up to, giving Acker this literary middlebrowbeating? The quotes she takes from Acker feel like prostheses inside her prose, Acker’s words clanging against her own so readers are reminded rather than confused about their provenance; the few details of Acker’s life she includes—her family’s wealth, her mother’s suicide—feel like disingenuous dimensions within Kathy’s happily-ever-after tale. All that is produced is a kind of veneering; Acker’s presence is evoked with about as much muscle as it takes to choose a photo filter for your selfie. The obvious answer, of course: Acker invites this cheeky, frisky relationship to an “I,” but Crudo still falls short because its formal stakes have too little depth. “You take what you find, it’s all material,” Laing writes. “I mean what is art if it’s not plagiarising the world?”

Laing’s isn’t the only book to conjure Acker’s spirit as of late. Chris Kraus’s rich and vivid 2017 biography, After Kathy Acker, is the result of years of research; Douglas A. Martin’s Acker, from the same year, weaves together the facts of her life and writing, and wonders about her legacy, how and why it has both lasted and languished over the years. As he writes in his opening paragraph: “Was she someone to follow in the footsteps of? Was she someone to let have a say for us, to accompany us through days, to take living cues from, someone to see an emerging self reflected in, who we might then try to emulate.” Other writers have picked up the threads she left behind, finding new ways of spinning them: Michael du Plessis’s mischievous, mournful The Memoirs of JonBenet by Kathy Acker (2012) Acker-ishly revives her as a doll for JonBenét Ramsey to play with. McKenzie Wark’s recent e-flux essay “Wild Gone Girls” (2018) entwines Acker’s writings with his own to map the continued relevance of her mind and work. In Matias Viegener’s gorgeous and haunting The Assassination of Kathy Acker (2018), he, her literary executor, tells the story of her death while taking stock of her afterlife as a literary figure: “Now she’s neither dead nor alive, or she’s both.” I cannot think of another writer who hovers over this moment in quite the same way, and I can only assume that for those who did not personally know Acker when she was alive, her restored presence fills a felt absence—perhaps of a kind of unbridled ambition for literature, a quality of writerly courage that thieves as a means to revolt and think anew, or of role models for how to be a woman who bows to no one and nothing save her own ideas and desires.

Next to Acker’s long shadow and the literature she has inspired, Crudo gives off little light. The fact that Laing wrote it in seven weeks has been touted almost as an act of experimentalism; the book’s dust jacket crows that its story “unfolds in real time.” (Confession: I happen to be an ardent guardian of the phony time of literature.) It doesn’t take a deep dive into that line to understand what’s meant: Crudo is diaristic, written, edited, and published quickly, and therefore its shortcomings, if not perceived as virtues, should be overlooked, excused. Laing is possessed of obvious gifts. And although marking a particular moment is a valorous enough goal for a writer, here she’s saying far too little about far too much. As Mary McCarthy once wrote: “The passion for fact in a raw state is a peculiarity of the novelist.” Although Crudo, which just so happens to mean raw, was intended as such, it feels, in the end, merely half-baked.

Jennifer Krasinski is a senior editor of Artforum.