Jennifer Krasinski

“YOU ARE about to enter the text at hand. It slides through your fingers, but it doesn’t matter, someone else will have to carry me through to completion, a mountain guide, not you!” So Elfriede Jelinek, museless, delivers us unto her slippery magnum opus, The Children of the Dead, published in 1995 and last year […]

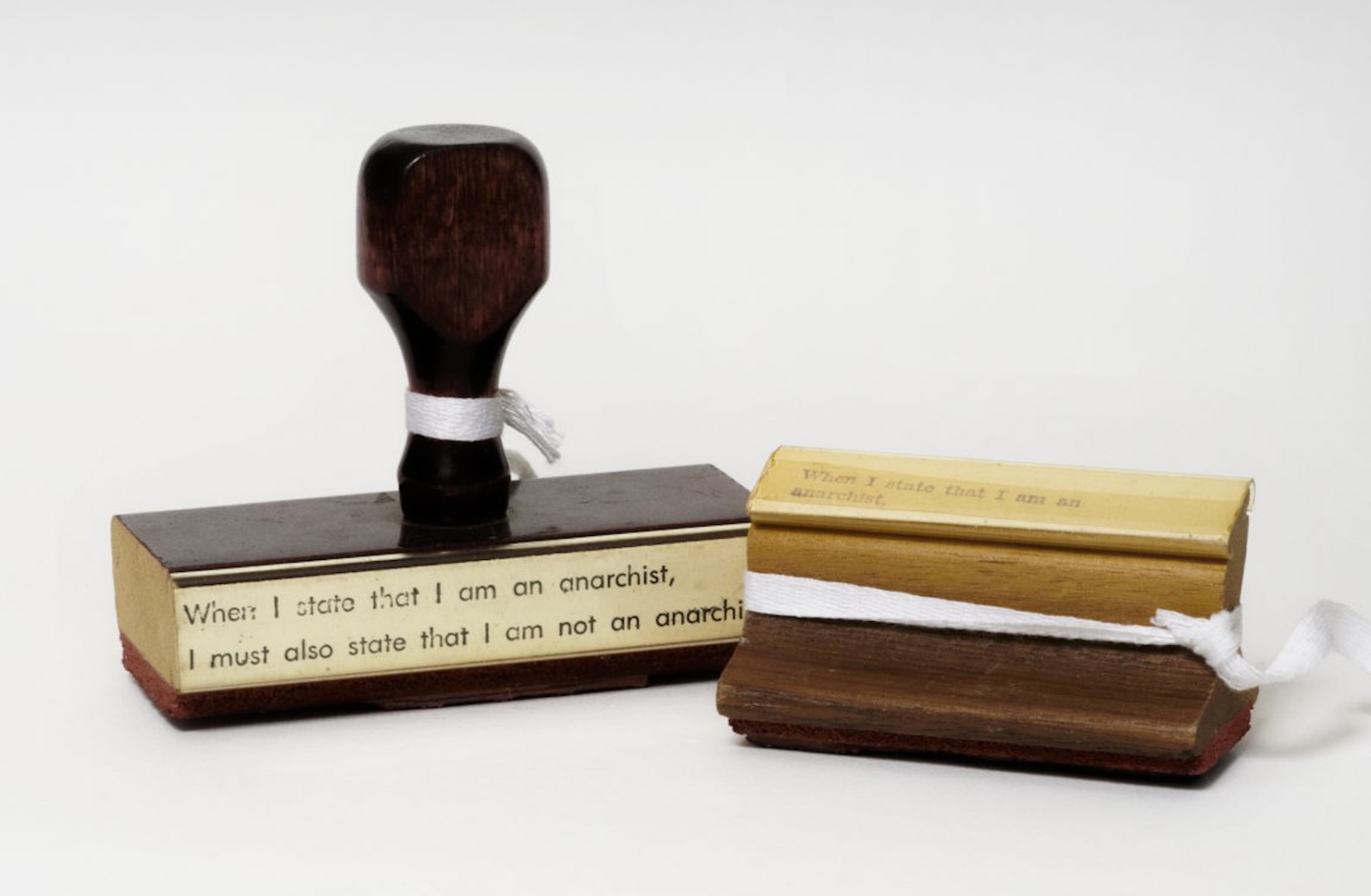

ON JANUARY 31, 1975, a twenty-year-old man approached the main entrance of the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, took off his jacket and shirt, threaded a steel chain through the door handles, then looped it around his wrists and locked it. On his back, stenciled in black, were the words: when i […]

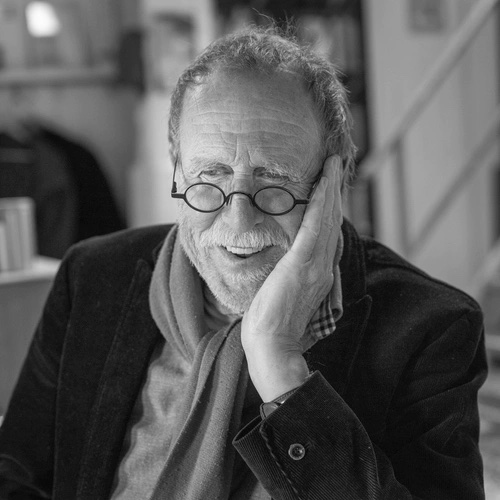

IN THE AUTUMN OF 2019, art critic Peter Schjeldahl learned that lung cancer had whittled all but about six months between him and oblivion. (Immunotherapy promised nothing but gave him three years. He died in October 2022 at the age of eighty.) Attention, as performed by Schjeldahl, had always been a live art form, his […]

IT IS A FITTING IRONY that when trying to describe Anne Carson’s sensibility, one quickly hits the limits of language. To measure the breadth of her brain across her twenty or so books, one might acquiesce to hyphen-chic—as in, she is a poet-translator-scholar-of-ancient-Greek-essayist-visual-artist-playwright-maker-of-performances-and-dances—but such frantic stitching would fail to impart how seamlessly entwined her practices are. To distinguish her literary occupation from that of other authors, one might be tempted to conjure a new word via the dark arts of negation—she is an uncontainer of ideas, or she de-forms thought—but that would belittle her writing as merely an act of resistance

BETWEEN 1956 AND 1967, the Coenties Slip on the lower tip of Manhattan was home to a group of artists who had moved to the city with grand ambitions for their work and little money to their names. In those lean years, before they were canonized, Robert Indiana, Ellsworth Kelly, Agnes Martin, James Rosenquist, Lenore Tawney, Jack Youngerman, and Delphine Seyrig all took up residence in this “down downtown,” on a dead-end street on the East River where they nested themselves among fishing ships and sailors, the changing tides and unremitting grime, living at a remove from the New York

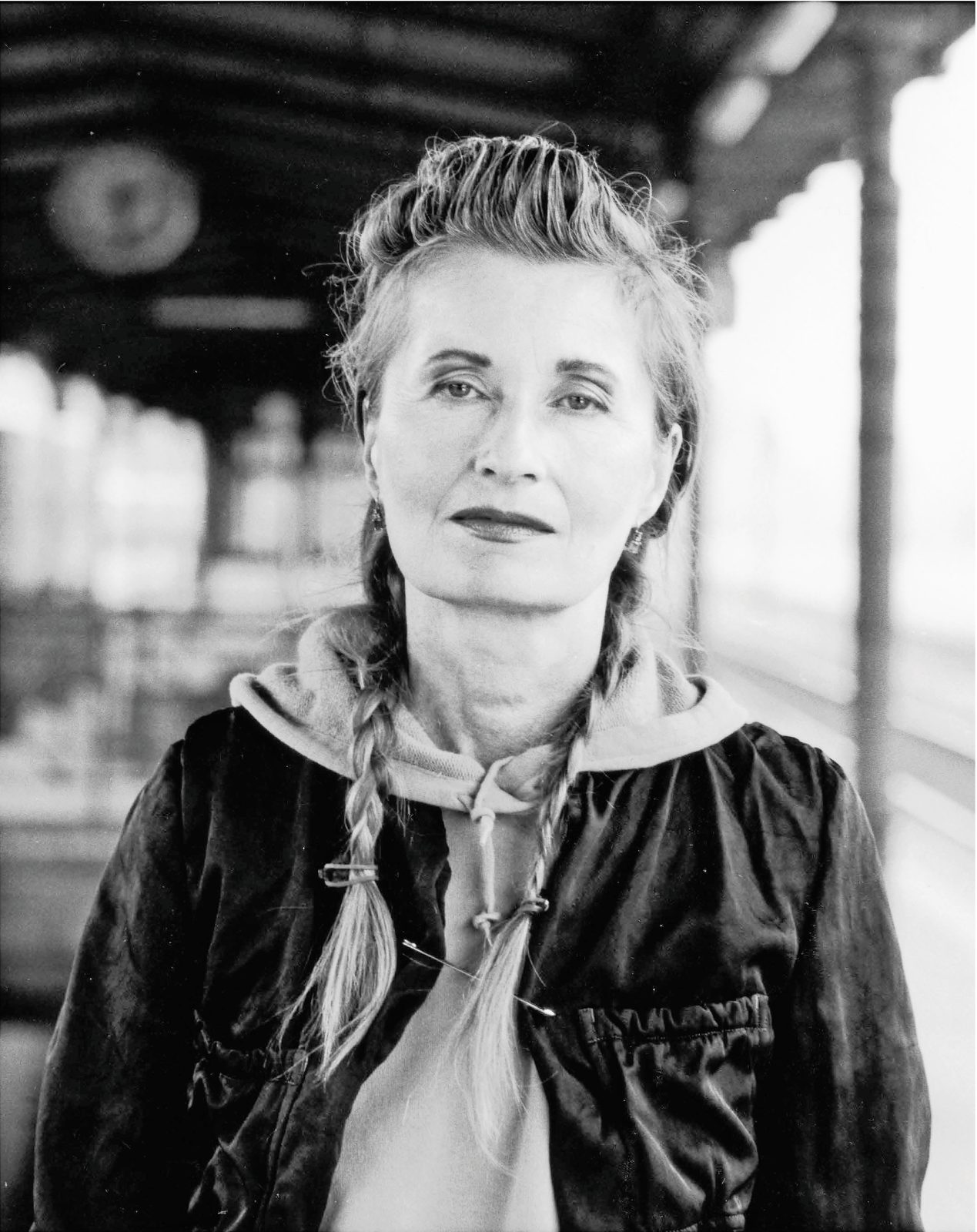

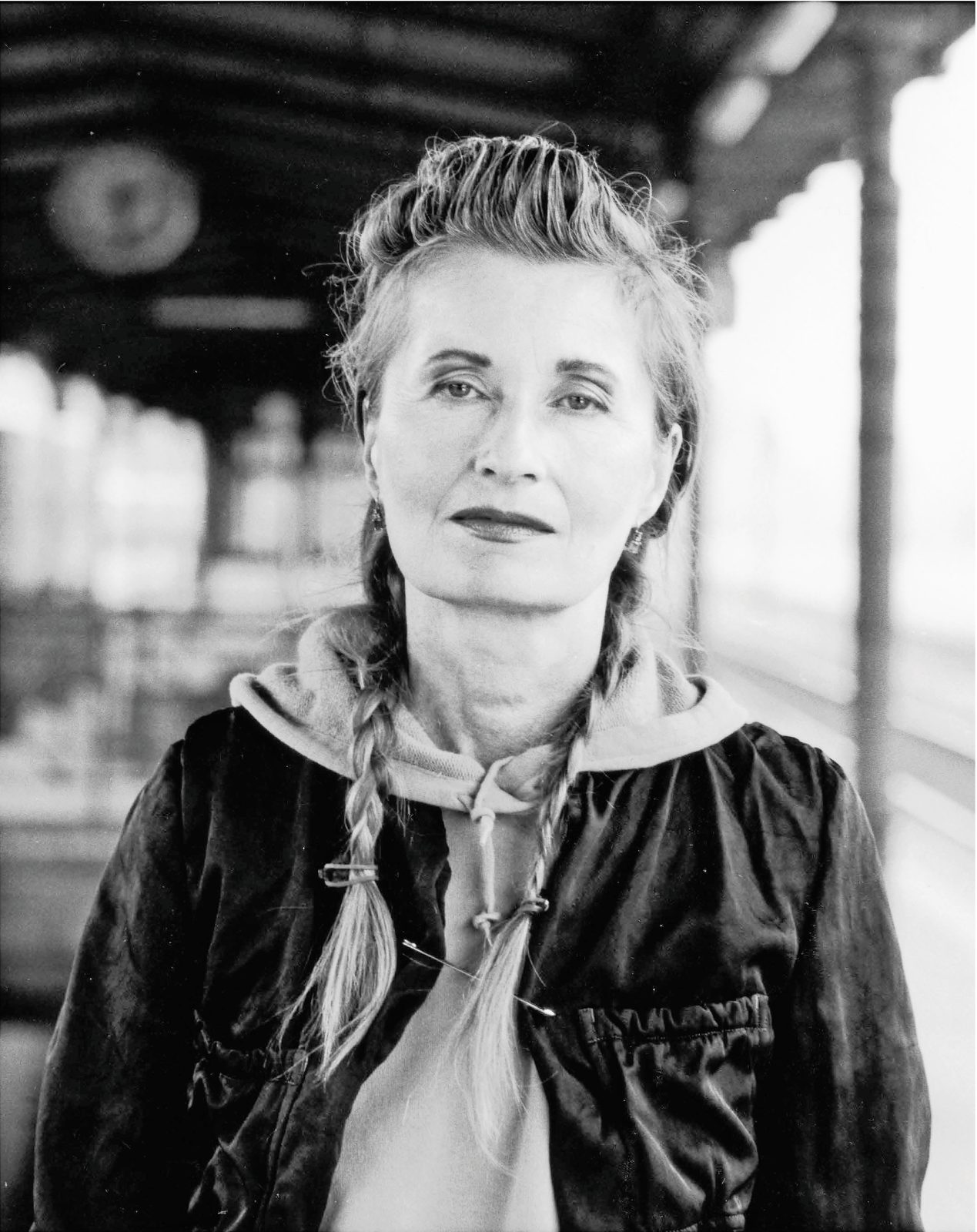

TO TELL THE STORY of another person’s life poses certain challenges to an author wanting to capture their subject in the truest light possible. In the introduction to her ebullient, poignant What Is Now Known Was Once Only Imagined: An (Auto)biography of Niki de Saint Phalle, Nicole Rudick offers up her strategy for honest representation: “What could be closer to the artist’s voice than the artist’s own voice, closer to her sensibility than that produced by her own hand?” Rudick edited this hybrid volume of text and images, selecting and sequencing Saint Phalle’s own writings and works on paper to

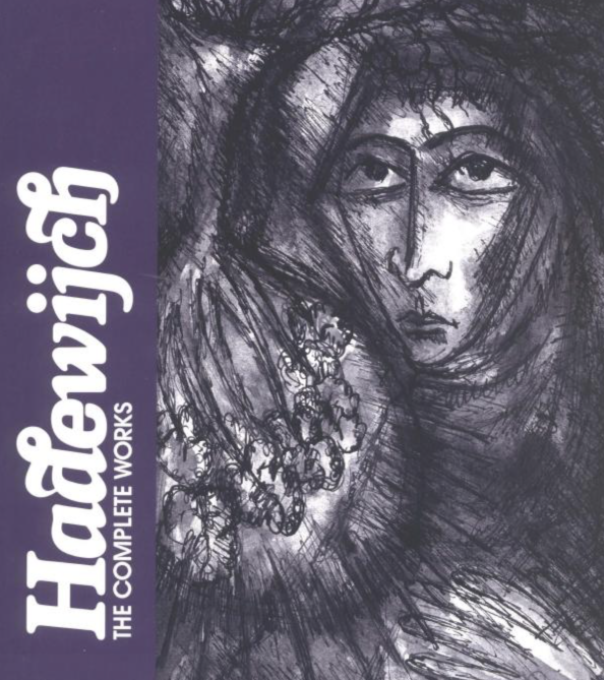

“WE FEEL AN AFFINITY with a certain thinker because we agree with him,” writes Lydia Davis in “Affinity,” one of the shorter stories in her collection Almost No Memory (1997). Yet according to Davis, it wasn’t a sense of kinship that led her to the zeer korte verhalen (zkv’s), or “very short stories,” of the beloved and prolific Dutch author A. L. Snijders (1937–2021). Rather, it was a sense of fairness: if her books were being translated into Dutch, then she should translate a work from Dutch into English. It would be no small challenge, since she would have to

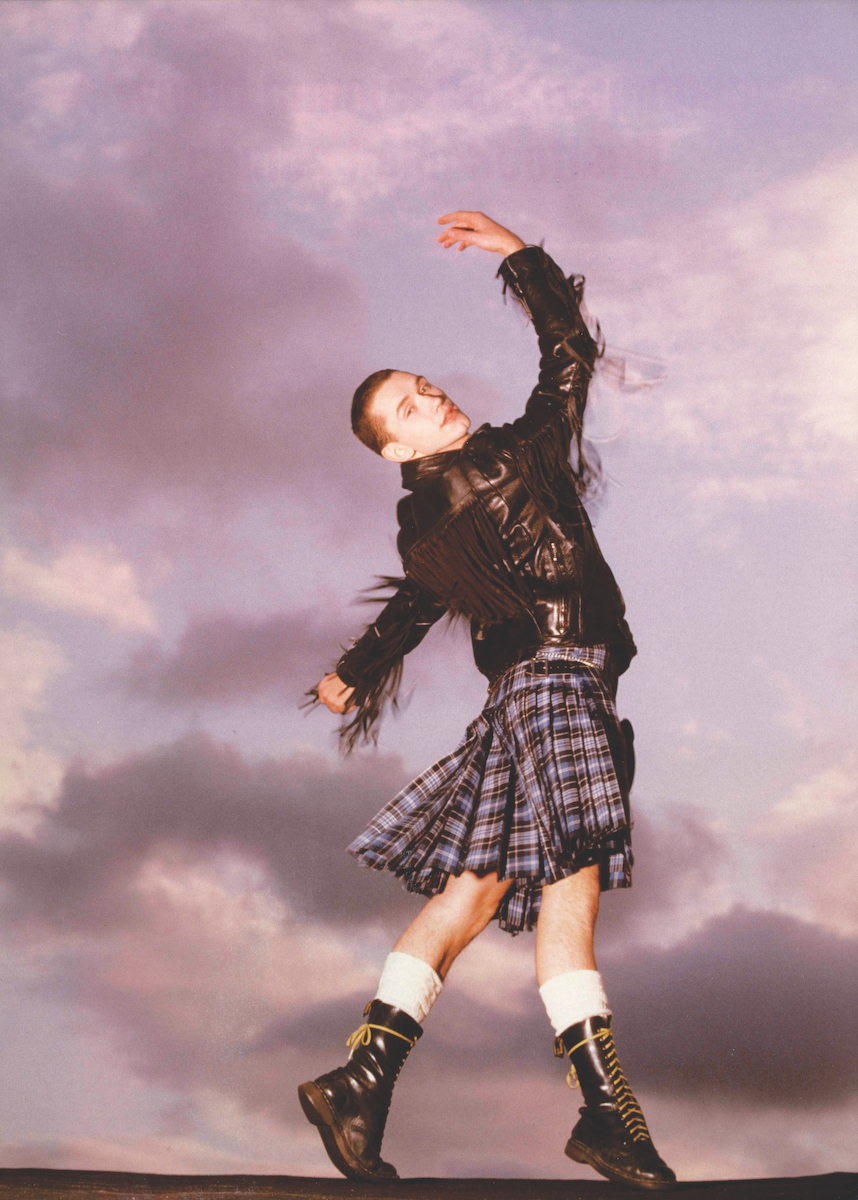

Michael Clark publicity photograph, 1986. © Richard Haughton IF DANCE IS HUMANITY’S REBELLION AGAINST GRAVITY, choreographer Michael Clark defied dance’s gravitas. He was classically trained: first as an Aberdeen boy schooled in traditional Scottish dance, then as a star pupil at London’s Royal Ballet School, later as a member of the Ballet Rambert, and later […]

DURING THE FIRST WEEKS of quarantine, I would become exasperated when I’d hear some expression of gratitude for the platforms and technologies keeping us socially connected, as though connection is only virtuous, or would be balm enough. It seemed apparent that the value of disconnection was an equally pressing lesson, a condition put before us to wrestle with, to practice, to sit with, and, perhaps, to learn from. Perhaps disconnection would even be essential to defining how and in what altered state we might arrive at the other side of this horrific, if expected, shakedown. Wanting role models for living

In 1971, for the month of July, powerhouse poet Bernadette Mayer documented her life by shooting a roll of 35 mm film every day and writing down as many experiences, ideas, observations, feelings, and sights as she could. From those materials, she created Memory, a fabled work of installation art that plunged viewers headlong into the fizzing slipstream of her consciousness. Disorienting and clarifying in equal measure, Memory uncovers the space between living and recorded life. If the latter is imperative to apprehending the tumult of human experience, it nonetheless falls very short of capturing its full measure. “It’s astonishing