DURING THE FIRST WEEKS of quarantine, I would become exasperated when I’d hear some expression of gratitude for the platforms and technologies keeping us socially connected, as though connection is only virtuous, or would be balm enough. It seemed apparent that the value of disconnection was an equally pressing lesson, a condition put before us to wrestle with, to practice, to sit with, and, perhaps, to learn from. Perhaps disconnection would even be essential to defining how and in what altered state we might arrive at the other side of this horrific, if expected, shakedown. Wanting role models for living apart from others, for putting this untethering to best, even most outrageous use, I began to pore over the writings of the female Christian mystics—Saint Teresa of Avila, Marguerite Porete, Julian of Norwich—and soon found myself particularly taken by those of the thirteenth-century beguine Hadewijch.

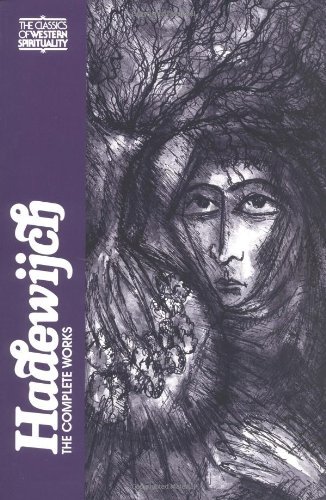

There are few biographical facts to perforate her extant texts, which total fourteen transcribed visions, sixty-one poems, and thirty-one letters, all collected in the 1980 volume Hadewijch: The Complete Works. Written in Middle Dutch, the vernacular of her time and place, all are ruminations on the pure, divine nature of minne, or love. She lived in Belgium as part of a caste of women who dedicated their lives to God but refrained from “taking the veil.” They did not marry, forsaking the running of households to form self-supporting communities. Hadewijch was head of hers until she was ousted for holding her peers to overly strict standards of faithful conduct. Even the threat of punishment and exile did not shake her faith in God’s will. As she wrote in a letter addressed to a beloved younger member of her group: “What happens to me, whether I am wandering in the country or put in prison—however it turns out, it is the work of Love.”

Hadewijch’s letters are passionate, didactic (most are assumed to be addressed to the aforementioned novice), offering practical spiritual advice in subjects ranging from how to conduct oneself on a pilgrimage to the four paradoxes one discovers when studying the nature of God and the two fears that love may stoke in a soul: that of unworthiness, and that love “does not love us enough.” Her poems, however, are unabashedly laced with eroticism, at times playfully aping the popular form of courtly love literature. After all, by what other earthly experience could humans conceive of the blissful dissolve of a self before God? This stanza, from a verse titled “Reason, Pleasure, and Desire,” reveals that Hadewijch’s lofty yearnings did not preclude those of the sensual world:

Love’s soft stillness is unheard of,

However loud the noise she makes,

Except by him who has experienced it,

And whom she has wholly allured to herself,

And has so stirred with her deep touch

That he feels himself wholly in Love.

When she also fills him with the wondrous taste of Love,

The great noise ceases for a time;

Alas! Soon awakens Desire, who wakes

With heavy storm the mind that has turned inward.

In one of her most vivid and peculiar visions, the mystic recounts a visitation from Queen Reason, “clad in a gold dress, and her dress was all full of eyes; and all the eyes were completely transparent, like fiery flames, and nevertheless like crystal.” With her foot on the beguine’s throat, the Queen asks if she recognizes her, and what follows leaves Hadewijch “inebriated with unspeakable wonders” and surer of her soul’s path and purpose.

Paradox is essential to the state of the mystic. They retreat from society in part to deepen their study of humanity, scrupulously following, imitating, that which can never be fully known: divinity. When I found myself tired of Hadewijch’s talk of God and Love—large, heavy subjects that often felt immobile even when buoyed by a wondrous faith—I would instead think of her more simply: as a person moved to better understand scale. At a distance from other bodies, yet highly attuned to the presence of overwhelming pain, suffering, violence, fear: This is how a person can know their right size, and thereby calculate how to deploy themselves in the service of relief. The lesson of Hadewijch isn’t merely about love; it is also about form, and the wild-mindedness that seclusion affords those in pursuit of new ideas. It is about the space it takes to imagine radically compassionate narratives with the hope that they will overtake those imagined for us. Any world to follow this one should be propelled by nothing less.

Jennifer Krasinski is a senior editor of Artforum.