There is little to recommend the rich, except of course their money. After all, the greater a fortune, the more likely it was ill-gotten. (No one ever hit pay dirt performing a good deed.) Until the revolution comes, we still have taste as the great leveler, evidence of democracy in action. What distinguishes good taste from bad, however, matters less than the fact of its presence at all. The worst plight is having no taste whatsoever, of being boring. Far better to vigorously exercise the right to get it all very, very wrong.

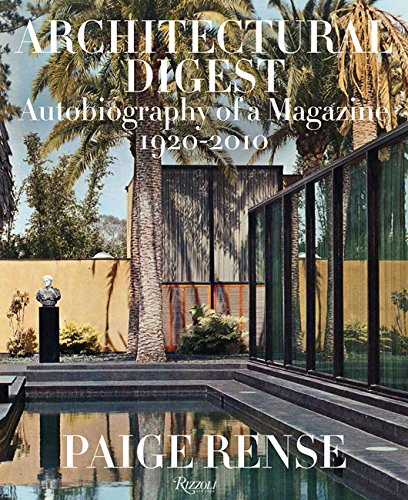

A delectable distraction from these bleak and crooked times, Architectural Digest: Autobiography of a Magazine 1920–2010 (Rizzoli, $65) is a history in words and pictures of the best-selling interior-design glossy, narrated by Paige Rense, its renowned editor in chief of forty years. It was under her leadership that the once Los Angeles–based trade publication transformed into the wildly popular monthly that granted its readers—whom Rense describes as “above average in intelligence and style”—exclusive looks into the private domiciles of the rich and famous. In its heyday, the magazine was powerful, influential; it fanned the flames of lifestyle fantasies for millions of readers, while firing up business for its featured designers, which included legends Billy Baldwin, John Saladino, Sally Sirkin Lewis, Marjorie Reed Gordon, Mario Buatta, Juan Pablo Molyneux, and Tony Duquette, as well as countless others. The coverage was determinedly reportage rather than criticism (after all, these were people’s homes), and the magazine boasted A-list contributors such as Kurt Vonnegut, John Irving, Truman Capote, Judith Thurman, John Updike, David Mamet, and Martin Scorsese. Philip Johnson famously referred to AD as “pornography for architects” (he later confessed to being a rabid reader), and it could indeed arouse, in no particular order: curiosity (morbid and otherwise), envy, sometimes a bit of inspiration, other times dull pangs of shame for failing to live in aesthetic perfection. Feelings of inadequacy could quickly curdle into harsh judgment, for unlike pornography, which peddles a certain promise, a plausibility, to its audience, the intimate encounters AD offered would almost certainly never be yours IRL.

I grew up reading the magazine, ogling worlds so foreign to me, the firstborn daughter of Catholic parents, living in the Midwest. (I had never heard of Mustique until David Bowie and Iman’s Indonesian-inspired hideaway on the island appeared in AD’s pages, alongside a portrait of Bowie looking terrifically fetching in a sarong.) My mother, who has a remarkable eye, was always the designer and decorator of our family home. She would often stack a few of the most recent issues on our living-room table, proof in certain circles that a cultivated attention was being paid to the house. When my parents moved to New Jersey years later, my mother wallpapered one of the bedrooms in looping flowered vines. On the bedside table was a copy of AD, on the cover of which was a bedroom done in the very same. I like to think of it as my mother’s meta decorative moment, proof that the room had fallen through the looking glass, and into the world of high design.

Two lessons I gleaned from reading AD: a certain politesse when navigating differences in style, and that words of praise, when used precisely, can at the same time sound like pejoratives. A four-poster ormolu canopy bed draped in clashing chintz prints might be the room’s pièce de jouissance. Framed family photographs piled high atop a grand piano so as to nearly crush it should be appreciated as personal touches. The velveteen, stuffed-to-bursting couches upholstered in the same champagne gold as the room’s wall-to-wall carpeting seem to bring the sunshine indoors. The magazine was never catty, or arch. It didn’t have to be when a reader would naturally provide her own subtext.

Then there is the taste that resolutely transcends any notion of good or bad, achieving singular heights of visual hyperbole. The unerring Vogue editrix Diana Vreeland famously told Baldwin—who made his reputation in part as a master colorist, yet whose favorite color was “no color at all”—that she wanted her apartment to look like a “garden in hell.” He obliged by wrapping her living-room walls in crimson floral fabric, with carpeting and upholstery all in matching hues to surround a visitor in red, red, red. The result is an eye-searing assault, somehow as wondrous as it is off-putting. In AD, a client’s eccentricities (e.g., those personal touches) were sometimes in the details—the needlepoint RR pillow on Ronald and Nancy Reagan’s couch—but more often than not were writ large. The herd of life-size faux sheep in Yves Saint Laurent’s library; the runway out the back door of John Travolta and Kelly Preston’s house in Florida, where the celebrity keeps his jets. Stenciled along the walls above the stately bookcases in Diane Keaton’s library-cum-entryway are the words THE EYE SEES WHAT THE MIND KNOWS. Huh. I googled the phrase, thinking perhaps it was some kind of popular New Age koan, but the first hit that came up was for the title of an article in a medical research journal regarding a rare case of a “traumatic pulmonary pseudocyst.” Double huh. All to say that it must mean something, at least to Ms. Keaton.

Although many mysteries of personal taste remain unsolved, Autobiography of a Magazine also serves up delicious morsels of Rense’s encounters with wealth, fame, and power. She tattles on Katharine Hepburn, who liked to walk around at night and spy on her neighbors through their windows. We learn that Coco Chanel never spent the night in her luxe apartment, using it only to host parties and take naps; instead, she preferred to stay in a quiet room at the Hôtel Ritz. Rense notes that Artie Shaw spoke at Capote’s memorial, though he’d never met the writer, and jokes that Jerry Lewis and his wife must have had five children because their bedroom was decorated predominantly in lavender, “a color some psychologists believe is most conducive to romance.”

Although Rense takes great pride and delight in her years at AD, she is quick to distinguish business matters from personal ones, no matter how the two might have overlapped. Rense grew up in a working-class family, and was a high school dropout who worked as an usherette at the Grauman’s Chinese Theatre before nabbing a job as a typist at WaterWorld magazine, where she met her first husband, Arthur F. Rense. (She would later marry the painter Kenneth Noland.) Her success story is narrated as a journey of luck, pluck, and eighty-hour workweeks. Rense is startlingly clear-eyed about her place in the rarefied worlds in which she traveled, and her candor, in the context of all that lucre, sometimes seems like an odd state of grace. Launching into a story about how she met the Reagans at a party thrown by Betsy Bloomingdale, she pauses and adds the following parenthetical: “Please remember that I knew such people were only interested in me because of my title at the magazine.” Sometimes she found herself among people who weren’t even interested in that. At a party in Paris to which designer Valerian Rybar had invited her, she found herself surrounded by a chichi international set, with whom she had nothing in common. “Monsieur,” she explained to one of the guests, “I am a magazine editor. California is my home. I am not rich. My blood is not mingled with that of the Habsburgs, and my dress did not cost twenty thousand dollars. I am neither married to, nor the mistress of, nor heir to one of the world’s great fortunes. Monsieur, I’m here on a pass.” And with that, the gentleman stood up from the grand banquette on which he and Rense had been sitting, and walked away.

Reality is a most unwelcome visitor, especially when one is busy beholding Shangri-las, but Rense makes sure the reader never entirely loses sight of it. Rybar, who with his partner Jean-François Daigre once designed a living room based on Versailles’s Hall of Mirrors, died practically penniless trying to keep up with the platinum-fanged wolves he ran with. Baldwin, one of the leading decorators of the American twentieth century, lived in a sumptuously appointed but modestly sized studio apartment. Rense recalls asking decorator Arthur Elrod why he addressed his clients as Mister and Missus when they in turn treated him so familiarly. “I only call them by their first names when the last check clears,” he explained, avoiding one of the great hazards of the interior-design game: becoming so close with your clients that one day they decide not to pay for your services any longer. It seems then, as now, creative labor had a knack for disappearing beneath the rubric of friendship. But Elrod may have underestimated how deeply appreciated he really was. After his death, Joan Perry, the widow of Columbia Pictures president Harry Cohn, had her backyard barbecue pit transformed into an eternal flame in the decorator’s memory. No mention of whether Perry grieved her husband with equal fervor and devotion. To include a detail so personal, I imagine, would have been gauche.

Jennifer Krasinski is a senior editor of Artforum.