Novels and films tend to portray postapocalyptic cities as either devastated or abandoned. While the former might take inspiration from photos of Hiroshima or Dresden, places long emptied of people can be somewhat harder to imagine. What would Poughkeepsie or Staten Island look like years after a plague swept the planet? Some hint can be found in David McMillan’s photographs of the town of Pripyat, Ukraine, and the environs around the former Chernobyl nuclear power plant. In late April 1986, a reactor there suffered a catastrophic failure that spread radioactive material for thousands of miles and forced the complete evacuation of the area—the so-called Exclusion Zone—within nineteen miles of the plant. In 1994 McMillan became one of the first photographers to visit the zone; he has returned twenty-two times since. His fascination with Chernobyl arose, as he relates to the author of this volume’s essay, from growing up during the Cold War and reading Nevil Shute’s 1957 novel On the Beach, in which several doomed characters await a wave of radiation advancing from a nuclear war in Europe.

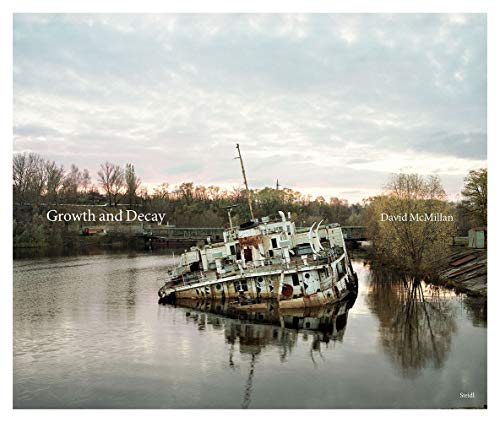

The color photos of Pripyat, once a thriving town of 50,000 people, reveal some scenes you might expect: cracked and empty streets, half-sunk boats, automobiles rusting in fields. But McMillian’s documentation of smaller-scale detritus summons a more affecting sense of the disaster’s magnitude and the particularity of the loss. Dust-covered toys in a kindergarten, piles of curled and yellowing hospital records, sneakers buried in a gymnasium’s rubble, and a plastic volcano on a classroom floor establish the tactile reality of daily lives interrupted and forever transformed on a spring day over three decades ago. Like Edward Burtynsky, another chronicler of environmental havoc, McMillan risks diminishing our empathic response with his artful composition and alluring, high-contrast printing. Still, despite this formal beauty, the sadness of a forsaken world remains inescapable.

The interlocking themes of growth and decay are dutifully borne out by photos of ferns sprouting in a hotel room, a bust of Lenin surrounded by weeds, and crumbling apartment buildings swallowed by vibrant foliage. But a deeper implication of the title pervades many of the images, especially his picture of an elephant slide (above). Where are the children who once slipped down the elephant’s trunk? Like the trees that have overtaken their playground, they have also grown. Their memories of that slide, their homes, and that spring day are surely fading. Just as buildings and statues decay, so, too, do those who lived in and among them. One day all that will be left of Chernobyl may be its name, and images such as these.