On October 17, 1973, Ingeborg Bachmann—the Austrian poet, novelist, librettist, and essayist—succumbed to burns sustained three weeks prior when she, tranquilizers swallowed and cigarette in hand, lay down to sleep and inadvertently lit her nightgown and bed on fire. She was forty-seven and had, since receiving the Gruppe 47 prize even before the 1953 publication of her first poetry collection, Borrowed Time, astonished the German-speaking public as well as esteemed peers with texts that pushed against tradition and played at the limits of language. She awed the likes of Günter Grass, Peter Handke, Uwe Johnson, Fleur Jaeggy, Elfriede Jelinek, and Christa Wolf; Paul Celan and Max Frisch fell in love with her, each in his turn.

“The most intelligent and famous female poet that our country has produced in the present century died in a hospital in Rome,” seethed her friend and fellow Austrian Thomas Bernhard in his story “In Rome,” a dissident elegy aimed at those who, citing her addiction to alcohol and pills, believed Bachmann alone was responsible for her tragic ending. “In reality and in the nature of things,” he wrote, “she was broken by her environment and, at bottom, by the meanness of her homeland, which persecuted her at every turn even when she was abroad, just as it does so many others.”

Her home sickness, as it were, was an acute condition Bachmann referred to as Todesangst, or “terror of death,” which first seized her in 1938 at the age of eleven, when Hitler’s army descended on her hometown of Klagenfurt to great fanfare. (“Austria’s Return Home into the Motherland,” boomed the March 15 headline of the Klagenfurt Times.) Although too young to comprehend all that was happening at the time, she later recalled being immersed in “this monstrous brutality . . . this shouting, singing and marching”—all in celebration, unwittingly or not, of the slaughter to come. Growing up beneath the bombs, walking familiar streets renamed for the Fascist regime, learning of the camps, the exterminations: Bachmann was forged inside of war and spent her too-brief life conceiving and writing a literature of resistance.

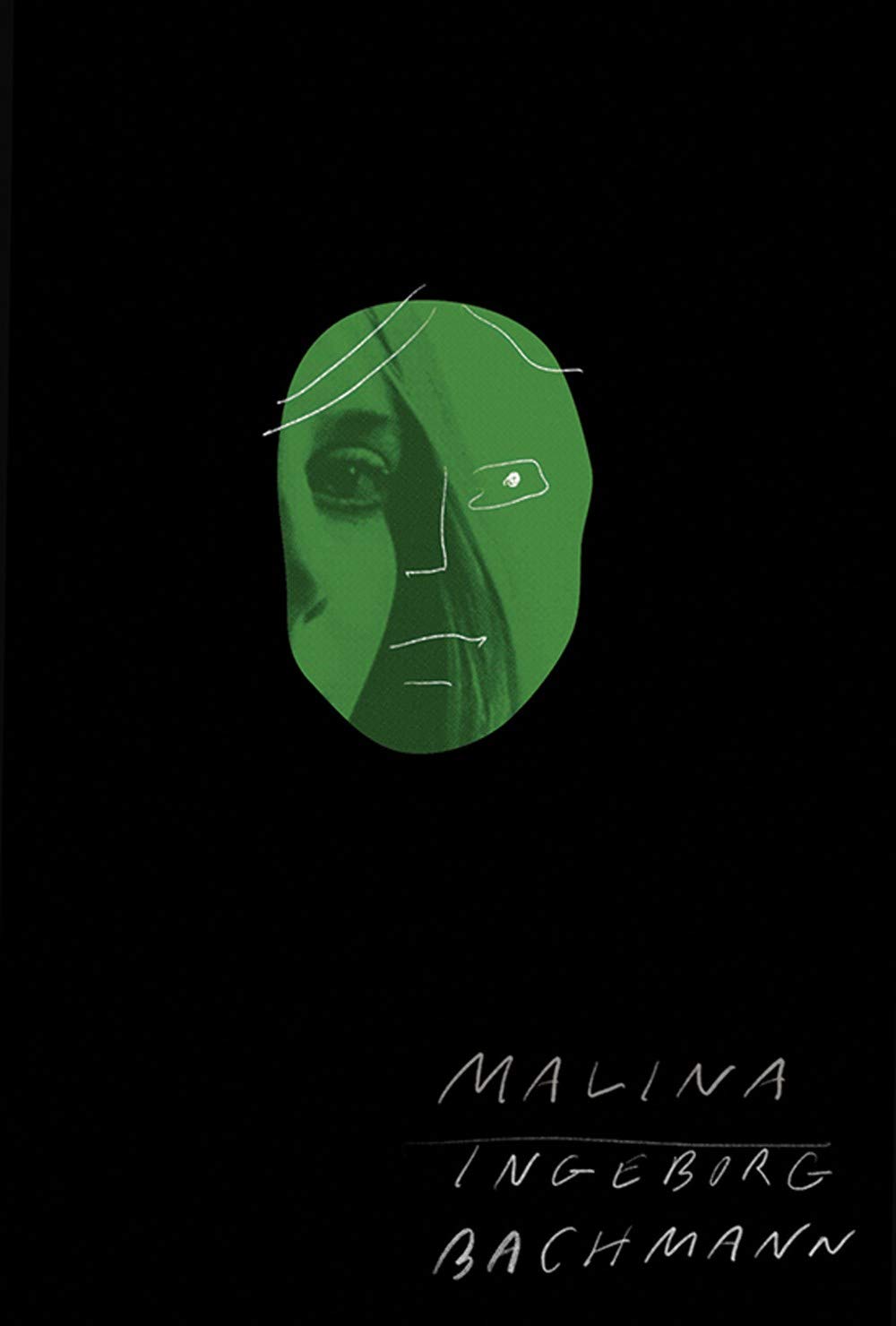

First published in German in 1971, Malina is the only completed novel in Bachmann’s “Todesarten” (Death Styles) cycle, which also includes The Book of Franza and Requiem for Fanny Goldmann, both released posthumously, unfinished. Bachmann intended for her trilogy to trace—to prove—how war is a condition and not merely an event, and how massacres are conducted routinely, hush-hush, beneath masks of civility. As she wrote in a prefatory statement to Franza that she delivered before public readings of the manuscript in 1966: “I maintain and will only attempt to produce the first evidence that still today many people do not die but are murdered. . . . Crimes that require a sharp mind, that tap our minds and less so our senses, those that most deeply affect us—there no blood flows, but rather the slaughter is granted a place within the morals and customs of a society whose fragile nerves quake in the face of any such beastliness.” She located the “first evidence” of such acts of violence in the savage dynamics between women and men.

Malina is a work of harrowing, head-spinning magnificence, and Philip Boehm’s new English translation—a revision of his first, which was published in 1990—brilliantly imparts the elegance of Bachmann’s mind, feral and full and excruciatingly alert. Comprising three chapters, each possessed of its own rhythm, tone, and texture, the novel is a love story of sorts, one shucked of all romance and sutured to disparate forms—the letter, the musical composition, the interview, the play, the fairy tale, the nightmare—all of which give her female narrator a distinct space from which to speak, to think, to remember, and to imagine. Bachmann’s is a deft miscreation, relaying the deranging realities of being a woman by way of sentences that rush forth like life force from an open jugular. As Bachmann told her audience in one of her landmark Frankfurt Lectures of 1959 and 1960: “If we had the words, if we had the language, we would not need the weapons.” Malina will perhaps be most perplexing to readers who believe that the most one can make of literature is perfect sense. Some of the novel’s firmer facts: The narrator is a writer of high repute who lives in the comfort and safety of “Ungargassenland,” as she dubs her quiet nation-street in Vienna. She is drafting a text that may be titled Death Styles, or Egyptian Darkness, or Notes from the Dead House. “Should this book appear, as someday it must,” she muses in a fleeting mood, “people will writhe with laughter after only one page, they will leap for joy, they will be comforted, they will read on, biting their fi sts to suppress their cries of joy.” These are perverse paroxysms, given that she also dreams her book will be about Hell.

At the story’s start, the narrator is in the throes of an all-consuming affair with Ivan, a Hungarian businessman and the father of two young boys. She also shares her life and home with a man called Malina, an erstwhile author now employed by the Austrian Army Museum. Regarding the different pulls between herself and these men, she explains: “Ivan and I: the world converging. Malina and I, since we are one: the world diverging.” Bachmann dissolves the sure borders around her heroine in part by relieving her of that cheapest and least revealing of designations: a name. Identifi ed only as “I” (Ich) when she is speaking, or “you” (Du) when she is spoken to, she retains a vivid but spectral presence, opening up ample room for Bachmann to think inside that divide. In one swooning passage, I parses the nuances of address, and how a pronoun must be mastered to express, to contain, a vast spectrum of feeling:

My “Du” for Malina is precise and well suited to our conversations and arguments. My “Du” for Ivan is imprecise, of varying hues, darker, lighter, it can become brittle, mellow or timid, unlimited in its scale of expression, it can be said alone at longer intervals and often, like a siren, always alluringly new, but nonetheless without that tone, that expression I hear in me whenever I cannot bring myself to utter a single word in front of Ivan. Not in front of him, but inside me I will someday perfect this “Du.” Perfection will have evolved.

But Ivan does not reciprocate her passion—or her courtesies or kindnesses. When she asks him what he thinks of love, he chides her for posing “impossible questions.” His compliments are at times just gilded cruelties: “Today you look twenty years younger.” His advice to her for keeping happy and girlish: “Laugh more, read less, sleep more, think less.” In one acid-laced turn, I recalls not only the great writers she has devoured over the years—the pre-Socratic philosophers, Kafka, Rimbaud, Blake, Freud, Jung—but also the wattages of the lightbulbs beneath which she read them. In the paragraph that follows, she makes dinner for Ivan from recipes she finds in cookbooks titled Old Austria Invites You to Dine and Little Hungarian Kitchen. This is Bachmann’s witty way of pointing up how winning a man’s affection routinely requires a woman to dumb herself down.

Ivan is gradually overshadowed in I’s thoughts by Malina, who looms larger as the story advances, looking after her, serving as her interlocutor as she balances and unbalances the world at large with the one in her head. Bachmann is at the height of her powers in the book’s second chapter, titled “The Third Man” after Carol Reed’s 1949 film noir set in postwar Vienna. Here, her prose glows white hot to illuminate the unthinkable—the deportations, the gas chambers, the murdered, the complicit—all the while refusing to reinscribe, or reify, fascism on the level of form. Across fifty pages, I’s memories and feelings and sensations force their way up and out of her depths in a series of labyrinthine dreams during which horrifying visions dance before her: “I am in Hell. The wispy yellow flames wreathe about, the fiery curls hang down to my feet, I spit the fires out, swallow the fires down. Please set me free!” Her epiphany after the dreams have lifted—“It’s always war”—would feel far more dystopian if it weren’t so clear-eyed, if her words had not so ingeniously disarmed her targets.

Rising from the novel’s darker undercurrents are briefer but equally robust swells: on the irrelevance of time (“for today twenty years have passed since I’ve loved Ivan, and it’s been one year and three months and thirty-one days on this 31st of the month since I’ve known him”), and solidarity (“what a strange word!”), and faith (“spiritual things demand constant humiliation”). One of the questions that hovers over Bachmann’s tale is whether (and to what degree) Ivan and Malina are real or refractions of I’s psyche. Another: Is a lover—or any “you,” whether benevolent or murderous—always some loosed shard of ourselves returning? How strongly one desires an answer may be the measure of a question’s potency, yet the richness of Malina is better fathomed by unmooring oneself in its murk, holding in mind the simultaneity of this and that—of flesh and thought, of love and contempt, of the death that lurks inside of life. The condition of paradox can be fiction’s prerogative and playground and—at a time when language is pulped from all sides in the pursuit of power—one of its most potent charges. As Bachmann’s books remind us: To cower in the delusion of certainty rather than reach for the greater and freer would damn us to fates we wrote long ago, ones we could have rewritten.

Jennifer Krasinski is a senior editor at Artforum.