An unseasonable snowstorm hit Casper, Wyoming, the day of Matthew Shepard’s funeral. The twenty-one-year-old gay University of Wyoming student had been robbed, beaten, tied to a fence, and left for dead in a homophobic attack by two men. His parents, Judy and Dennis, were able to fly from Saudi Arabia, where Dennis was working, just in time to be by his side as his heart failed. As they pushed themselves through “a week when absolutely nothing made sense,” they were told that a group they’d never heard of, the Topeka-based Westboro Baptist Church, was planning to picket their son’s funeral. The church had become notorious for staging extravagantly hateful demonstrations at memorial services for gay AIDS victims, shouting at mourners and carrying obscene placards. The city of Casper made an emergency decision to ban all protests within fifty feet of the funeral and encouraged the family to take other protective measures. “When all that interest ultimately manifested itself in protests outside the memorial service, a guest list and tickets just to make sure my family members and loved ones could get a seat in the sanctuary, a SWAT team, and Dennis in a bulletproof vest, it was overwhelming and scary,” Judy recalls in her memoir. “I wished with every bit of energy I had left in my body that everyone would just go away.”

Despite the outsize effect that her family had on the Shepards, Megan Phelps-Roper, granddaughter of Westboro Baptist Church founder Fred Phelps and active picket-line participant until 2012, discusses Matthew’s death only twice in Unfollow, her new book about her experiences in the church. The first instance comes when she remembers how mad she was about his death, “not because of his murder, but because it wasn’t my turn to travel to picket his funeral.” The second is after she’s left the church, when she encounters, during a tour at the Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles, a photo of her sister and grandmother picketing the trial of one of Shepard’s killers. After she admits that she’s related to the women in the photo, the docent praises her for “standing up” to hate and bullying. “It’s so hard to frame the words to admit that what I so passionately believed for so long was wrong and destructive in many ways,” Phelps-Roper remembers saying to the friend who accompanied her. “I can’t help but feel like I’m betraying my family every time I open my mouth about any of it.”

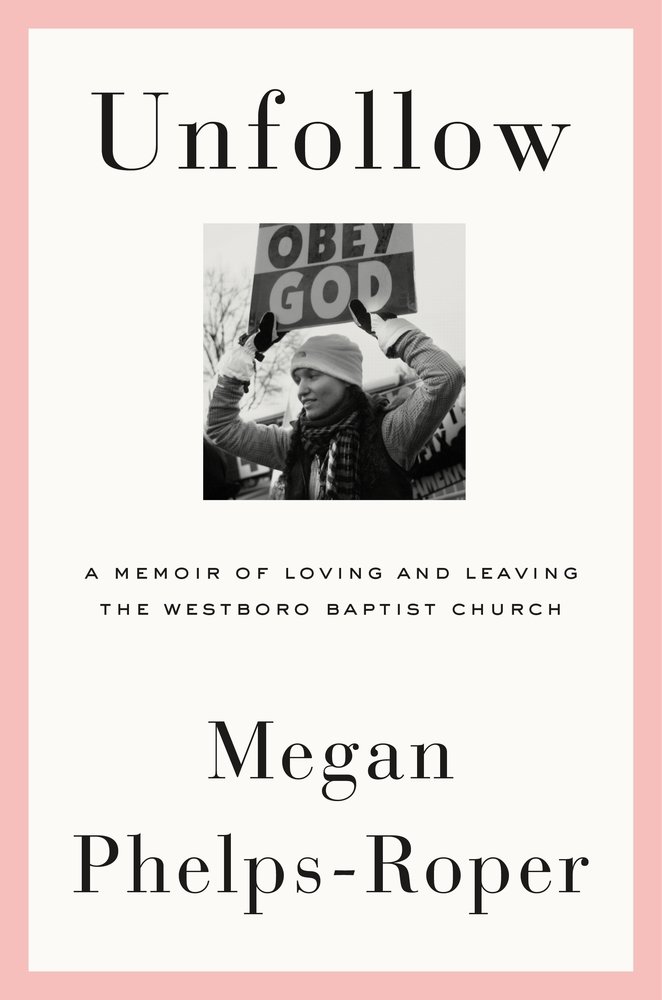

Unfollow aims to offer a cautionary tale about the “destructive nature of viewing the world in black and white, the danger of becoming calcified in a position and impervious to change,” and the ways that such rigid worldviews can break a family apart. Phelps-Roper details the doubt that eventually crept into her mind and led her to sever ties with the congregation and her family. Since that break, she has become a TED Talk speaker on the dangers of extremism. It’s true that Phelps-Roper is in a unique position to dwell on the inner workings of an extremist group—as a once-active Westboro member, she’s familiar with the ways that group dynamics and values can become distorted. But ultimately, Unfollow is too focused on her own escape from the church (and on the family members who remain ensconced in it) to shed much light—or to show much empathy for those whom Westboro so ruthlessly targeted, often at their most vulnerable.

Twelve at the time of Shepard’s funeral, Phelps-Roper was at that point already a seven-year veteran of Westboro’s picket lines. Unlike fundamentalists who retreat from American culture, the church sought direct confrontation with what it saw as evil in the world, and enlisted children to start spreading the word of God at an early age. Phelps-Roper and her ten siblings all went to Topeka public school, and the family’s extreme religious education at home prepared them for encountering movies, books, and music full of “depictions of sinful behavior.” When fundamentalist Christians urged Phelps-Roper’s mother to shun television and popular music, she admonished: “How can you preach against the abominable teachings that litter the landscape of this nation if you don’t even know what they are?” The church was also incredibly media-savvy and quickly adapted to the digital age. “You think the Internet was created by God for these pornographers?” Fred Phelps said at one point. “The heck you say. He created it for us. For our preaching.” As Phelps-Roper got older, she threw herself into managing the church’s social media, an important part of the group’s outreach and publicity machine. Writing and responding to hundreds of tweets per day, she came to love the platform, as it allowed her to circumvent the “distorting lens” of journalists and connect more directly with its users.

Twitter also taught Phelps-Roper new ways of communicating, some that were at odds with the way her mother and other church elders spoke to the public. Though the church was known for its dramatically insensitive taunts, Phelps-Roper came to realize that the 140-character limit made her prioritize information over insults. “Though I was always afraid I wasn’t sufficiently articulate to speak for the church, I never let that stop me from stepping up to the plate,” she remembers, “and the more I spoke, the more I learned how to speak.” As her communication style became less hostile and more explanatory, she found that she was able to convey the church’s values in a way that might have more appeal to outsiders than Westboro’s typical hate-speak. She grew frustrated by “the church’s refusal to consider how our words and actions would be construed by our targets.” Online, she says, she learned how to speak to others with reason, even respect.

Twitter was also where she met “C.G.,” the man who would eventually become her husband. During their marathon Words with Friends matches, he would ask about the church’s theology and funeral picketing. “My answer[s] sounded more and more hollow as time went by, but I refused to admit how uneasy—almost guilty—this line of questioning was making me feel,” she remembers. “When I wanted to talk about commandments and truth, C.G. was focused on humility, gentleness, compassion.” In Phelps-Roper’s view, these qualities were increasingly absent in the church’s new leadership, which was disciplining both her mother and younger sister for supposed infractions that had nothing to do with scripture. One day, Phelps-Roper experienced a kind of revelation: “There was something terribly wrong at Westboro. God was not in this place,” she writes. “We were not special. Not hand-selected by the Lord to do His divine work. We were a deluded people.” After leaving the church, Phelps-Roper found a new message to spread, becoming, per her author bio, a “writer and an activist” on “extremism and communication across ideological divides.” Phelps-Roper’s conversion story has found an eager audience. The New Yorker ran a profile of Phelps-Roper in 2015, and her 2017 TED Talk about leaving the church has been watched more than eight million times.

There is, unfortunately, a dearth of real outreach in Unfollow. Although Phelps-Roper believes her experience can help others appeal to people who are immersed in reactionary beliefs, she seems most engaged when she’s talking about her own family members who still belong to Westboro. “As the longtime recipient of so much love, attention, and care from my family, for me to simply abandon them seemed like the height of ingratitude, a failure to reflect the kind of person my parents raised me to be,” she explains. This is understandable—leaving a family is hard. But her focus on the family highlights what the book is lacking—a sustained effort to grapple with the divisions that Westboro created with a vengeance. “My family remained stuck in a pattern of thinking and behavior that inflicted unnecessary harm on themselves and on the communities they continued to target every single day,” she writes. What goes unanswered is how getting her family out of this holding pattern will actively help the communities they’ve spent their lives vilifying.

Despite being an expert on “communication across ideological divides,” Phelps-Roper rarely seeks out anyone who might truly challenge her. She is drawn to others with strong religious backgrounds: Her first stop after leaving her family is an Airbnb run by two Jehovah’s Witnesses, and she later befriends an Orthodox Jewish blogger who was number two on a list of “100 Most Influential Jewish Twitterers.” Most egregious is her “outreach” to the groups that Westboro attacked, gays and lesbians in particular. Phelps-Roper has coffee with a gay couple, an event she views as “another occasion to push back at the Us/Them divide.” But one member of this couple was the journalist who helped Phelps-Roper with her rollout strategy for her announcement that she had left the church. She does not seek out Judy Shepard, or anyone else who experienced Westboro demonstrations at their loved ones’ funerals. Or if she does, she does not report what happened. Overall, Phelps-Roper’s victims don’t factor into the story, aside from the shame that she feels at having participated in their victimization.

At one point, Phelps-Roper draws an analogy between her leaving the church and a gay person’s coming out. But to my knowledge, the New Yorker has not run a profile of someone for simply coming out. At times like this, the author can’t help but reveal who she really empathizes with—her family, and herself. Unfollow is far more concerned with the haters than with the hated. In this sense, the book might be helpful to people who want to lure others out of extremism. As for those who have been tormented by groups like the Westboro Baptist Church—they’ll have to wait for another book.

Maggie Foucault is Bookforum’s associate editor.