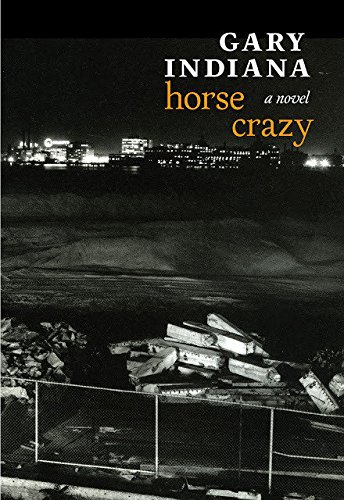

“AFFECTION IS THE MORTAL ILLNESS OF LONELY PEOPLE.” So says the unnamed narrator of Horse Crazy, a book about many things, but maybe most vividly the wages of loneliness. A longing for profound human exchange, a communion of flesh and mind, courses through Gary Indiana’s novel, his first. The setting is New York City in the 1980s; the narrator, reluctantly shackled to an esteemed downtown publication for which he writes scabrous and lucid art reviews, pines for Gregory, a beautiful if vainglorious former junkie drowning in self-pity and solipsism who gives the critic suggestive shoulder rubs but denies him sex. Gregory is a whiner, a flake, a prima donna. He bitches about his job serving trashy Europeans at an even trashier French restaurant. His sole passion, besides himself, is his art: X-Acto-knifed collage meditations on the commodification of bodies that he hopes will one day bring him fortune and fame. The narrator is not unaware of the emotional sabotage that Gregory traffics in, he even suspects he is being taken for a ride, but he chooses to look away. He is the masochistic moth courting the flame. All he wants is love.

But love is elusive. In the background, the city is splitting apart, riven with illness and greed. On the Lower East Side, Horse Crazy’s gentrifying ground zero, sushi restaurants and starched suits and enameled ladies do battle with the neighborhood’s leprous graffiti surfaces, its “ethnic clutter,” its last rent-controlled ratholes. “Nobody shoplifts anymore,” the narrator complains. “I remember when everyone did it, it showed your contempt for the capitalist system.” In the background a chorus of “sarcomas, pneumonias, and neuropathies” reign as AIDS rips through the city, preying on its poorest and most vulnerable. The days of “sexual pot luck” are over as the virus ravages prone bodies, demonizes its carriers, scandalizes touch. A blow job with a condom is so depressing: “Licking the penis without inserting the head into the mouth was like eating the cone and throwing away the ice cream.” In Indiana’s novel, illness looms as real life and as metaphor.

Someone once said we re-create the pictures we grew up with. When I picked up the recent reissue of Horse Crazy a few weeks ago I was knocked over by its uncanny and insistent echoing of our pandemic present. One of its lessons: The government will not save you. Another: It will fuck you over. Like the AIDS epidemic that preceded it, the virus among us, the one with the monarchical name, incubates fear and crystallizes difference. Sardined in narrow apartments and deprived of human touch, legions are lonely. Others, bereft of savings and health insurance, flail in pathos and precarity. Secure in their antiseptic privilege, the rich flock to islands and countryside compounds. That the coronavirus robs its victims of taste and smell feels like an ironic detail only Gary Indiana could have hallucinated.

In the world of the novel, the critic does not get laid and he loses the boy. In “real life,” the craven and commodity-crazed culture he bemoans—a culture where “everything and everyone is for sale”—takes over and the yuppified city that the novel prophesies comes to be. In this psychically bankrupt landscape, the prospect of a developed inner life is less than dim. So is the prospect of real connection. Horse Crazy makes vivid a crucial truth: Capital has its own disease-like logic. It leads to spiritual anomie. Love, that elusive thing, almost always out of grasp, is the only balm.

Negar Azimi is senior editor of Bidoun.