Negar Azimi

SHE CALLED HERSELF a minor writer. “I’m no Tolstoy,” said this woman whose parents named her after a character from War and Peace. One wishes Natalia Ginzburg hadn’t apologized for her gifts. Wishes that she had luxuriated in her standing as one of Italy’s finest postwar writers. The fact that her various novels, novellas, and essays are flying back into print—some freshly translated—thirty years after her passing is not unrelated to the extravagant success of the other Italian, the one whose books have become the stuff of prestige television. Ginzburg, alas, has no HBO series attached to her name, but

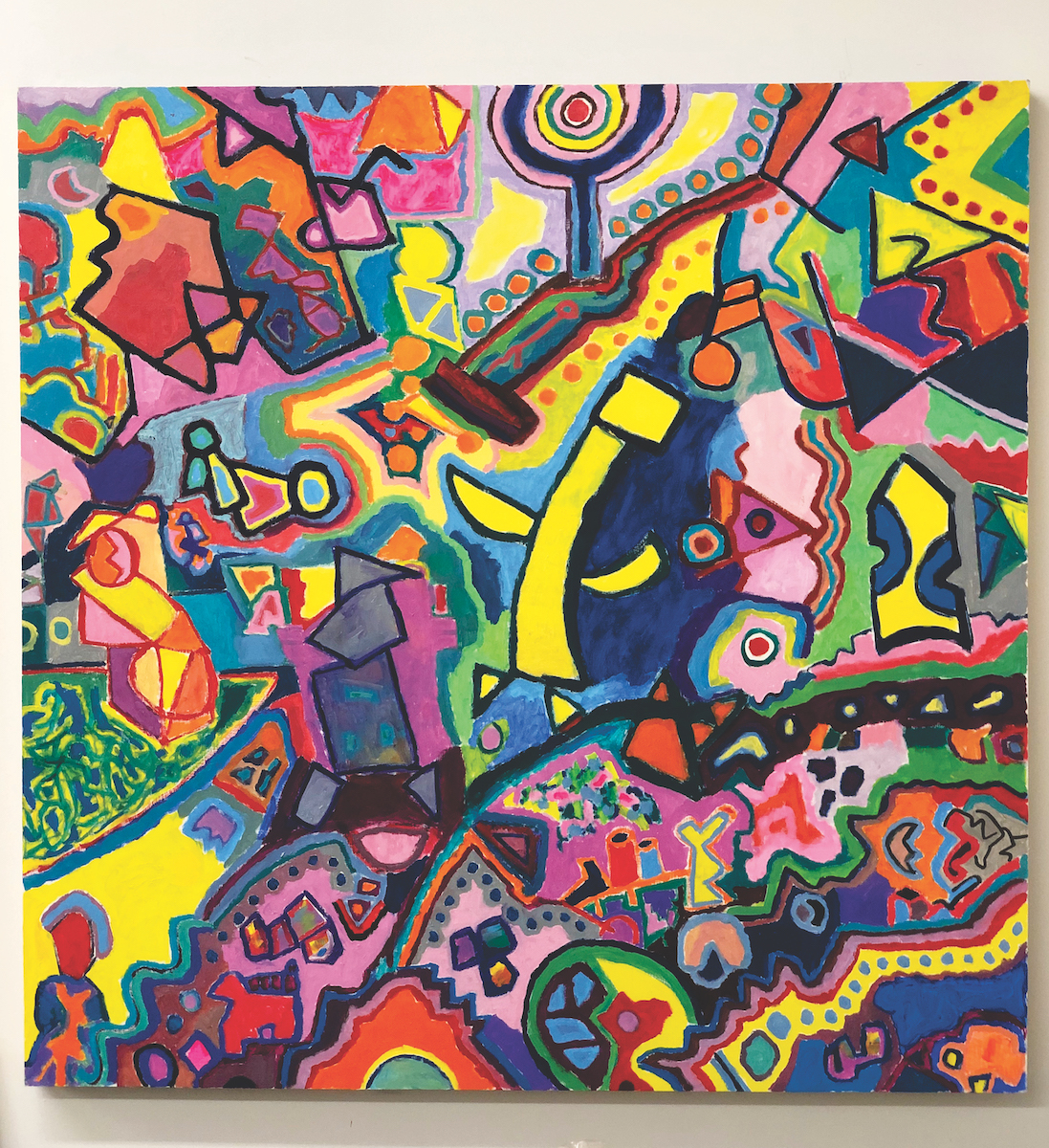

IN THE ANTIC TALE that opens The Cheerful Scapegoat, Wayne Koestenbaum’s book of self-described “fables,” a woman named Crocus, like the flower, arrives at a house party wearing a checkered frock designed by the Abstract Expressionist Adolph Gottlieb. She cowers in the entrance, vacillating over whether to enter or not. She phones her doctor, a man whom she refers to as the “miscreant-confessor,” who entreats her to be social. Inside, Crocus accompanies a “fashionable mortician” to a bedroom where she happens upon a fully clothed woman lying atop a fully clothed man. Observing something “unformed and infantile” about the man’s

“AFFECTION IS THE MORTAL ILLNESS OF LONELY PEOPLE.” So says the unnamed narrator of Horse Crazy, a book about many things, but maybe most vividly the wages of loneliness. A longing for profound human exchange, a communion of flesh and mind, courses through Gary Indiana’s novel, his first. The setting is New York City in the 1980s; the narrator, reluctantly shackled to an esteemed downtown publication for which he writes scabrous and lucid art reviews, pines for Gregory, a beautiful if vainglorious former junkie drowning in self-pity and solipsism who gives the critic suggestive shoulder rubs but denies him sex.

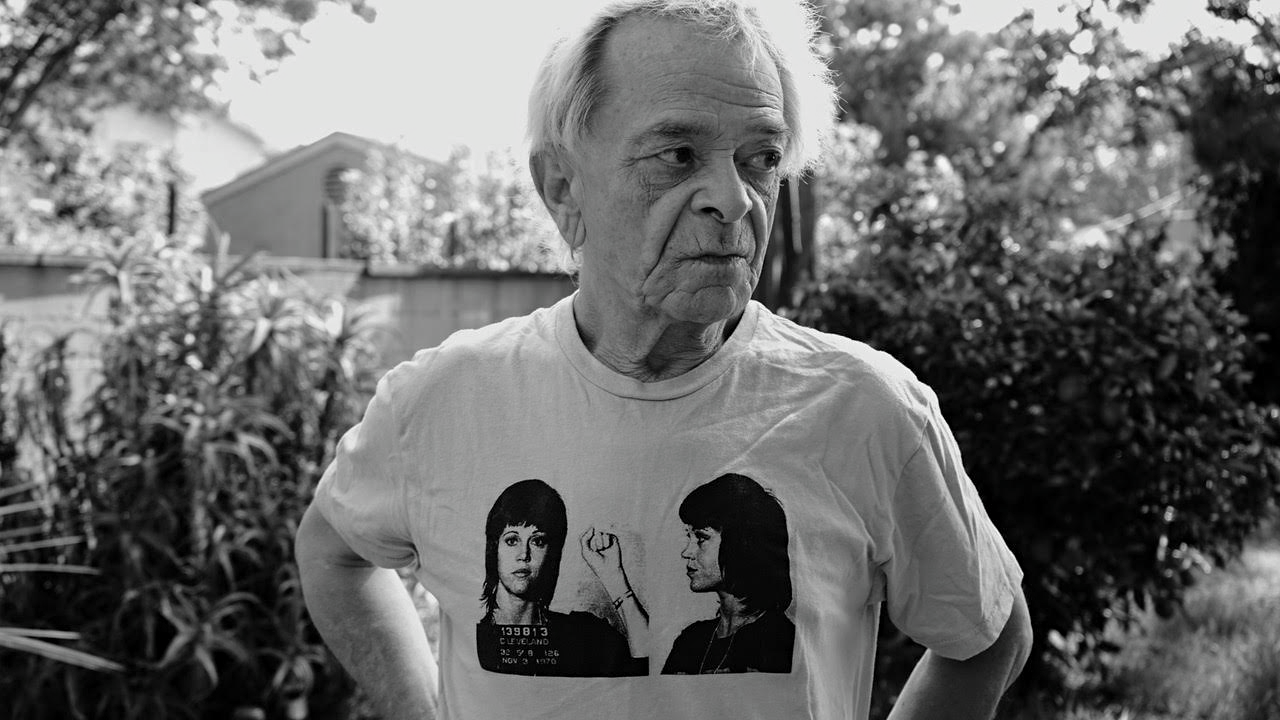

Octogenarian, slight, and frizzy-haired, Sonallah Ibrahim is a bit of a grump. For over five decades, the Egyptian novelist has served as the Arab world’s preeminent bard of dashed hope and disillusionment. His oracular if gloom-filled books are blinding inventories of consumerism, degradation, dictatorship, stagnation, pleasureless sex, creeping Islamism, and mind-numbing Americanization. To be alive and conscious, suggests Ibrahim, is to be humiliated. He lives in Cairo, the city of his birth and the mother of endless annoyance. “I’m so irritated most of the time by the dirt, the noise, and the commotion, but nevertheless I find that I can’t

It’s six o’clock in Tehran and Kate Millett needs a drink. It’s not easy, being a maquisard of the feministas. It is March 1979, only weeks after the departure of the Shah of Shahs. Iran is in the throes of revolution. Streets are being renamed, monuments defaced, pissed upon, torn down; there is graffiti everywhere. Call it the chrysalis phase after five decades of Pahlavi absolutism: No one knows what’s being born, but everyone wants it to be beautiful. (Beauty, alas, is in the eye of the beholder.) Millett, forty-four years old, tousle-haired and bespectacled in the frog glasses of