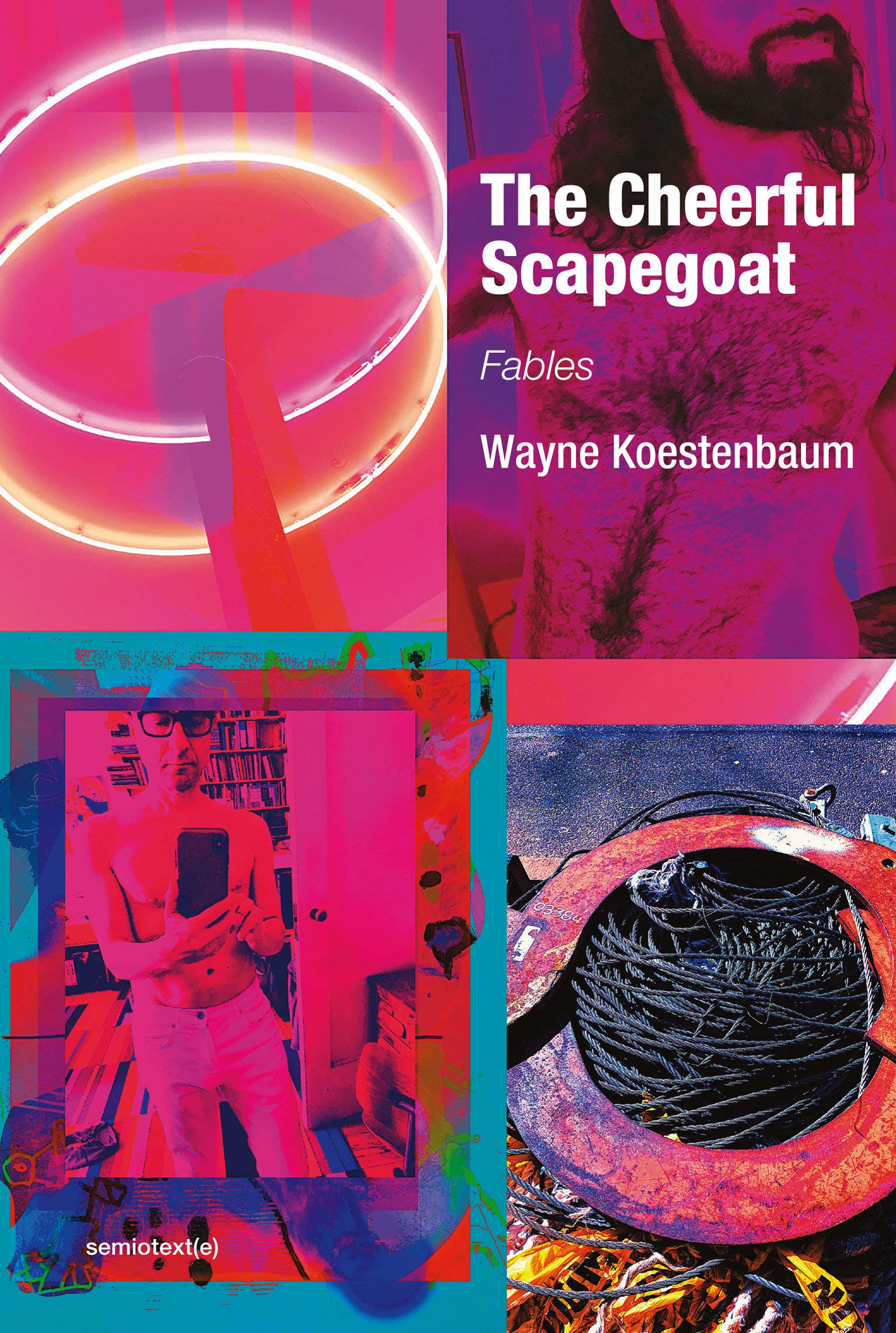

IN THE ANTIC TALE that opens The Cheerful Scapegoat, Wayne Koestenbaum’s book of self-described “fables,” a woman named Crocus, like the flower, arrives at a house party wearing a checkered frock designed by the Abstract Expressionist Adolph Gottlieb. She cowers in the entrance, vacillating over whether to enter or not. She phones her doctor, a man whom she refers to as the “miscreant-confessor,” who entreats her to be social. Inside, Crocus accompanies a “fashionable mortician” to a bedroom where she happens upon a fully clothed woman lying atop a fully clothed man. Observing something “unformed and infantile” about the man’s features, Crocus is overcome by a feeling of revulsion, “as if she were looking at a Chardin painting for the first time and were not comprehending her ecstasy—a conundrum which forced Crocus to shove her rapture into a different medicine-cabinet, a hiding-place christened ‘Disgust.’” From this point on, any attempt to pithily encapsulate what happens is doomed. Here is a snippet:

“I’ve finished blowing him,” said the woman to Crocus, “and now he’s virtually lifeless, a passive slob, dreaming of unsolvable equations.”

“Do you regret blowing him?” asked Crocus, newly enamored of this woman, because of her suave way of jettisoning responsibility for the man she had blown.

“I don’t yet know you,” said the woman, whose name, Crocus would momentarily learn, was Jesse, “but something neutral and flat in your demeanor suggests that we might together form an army.”

It’s a winningly odd exchange, Jane Bowles–ish in its drollness and abstraction. The story zigzags along, ending badly for Crocus, who is surrounded by party guests determined to sacrifice her as she dances to the antique sounds of a harpsichord. The sinister tale recalls the work of the other Bowles, Jane’s husband Paul. In his short story “A Distant Episode,” a hapless professor of linguistics is kidnapped in the Sahara and spectacularly molested—dressed in tin cans for the pleasure of his captors, his tongue excised. But before supplying us with the details of Crocus’s presumably gory end, Koestenbaum suddenly stops. He offers these final words: “Now we must efface this sordid investigation by rubbing a turpentine-soaked rag over the figure’s already smeared features.”

There’s a lot of that kind of thing in these fifty-three elliptical fables, a self-conscious staginess, a sense that “plot” and “character” are being assembled (and dissembled) right before your eyes. A little like a painting in progress that you might feel ambivalent about; you can always rub it out with a turpentine-soaked rag.

This concern with art and the serendipities of its making is not incidental. Nearly all of these irreverent texts, many of which feel like prose poems and are as short as a page and a half, are the outcomes of invitations to write about artworks. Koestenbaum, who took up painting sixteen years ago and has been known to name his colorful canvases after novels, is an atypical cultural critic, an author for whom the rapturous mode comes as naturally as breathing and whose criticism can often feel like a form of autobiography. His profuse corpus, both inspiring and intimidating, includes twenty books of essays and poems and unclassifiable miscellanea including a volume on Andy Warhol—one of the most original meditations on its elusive subject ever written—and a tour de force on opera and its audiences called The Queen’s Throat (1993). In addition to the books and the distinguished professorship at cuny, there’s the piano playing (and accompanying lounge acts), the painting and budding video-art career, the reservoirs of knowledge on porn, Jackie O., and Harpo Marx.

Thankfully—I say hallelujah with feeling—there is none of the dreary due diligence endemic to art catalogues and exhibition press releases here. The queer “art texts” in The Cheerful Scapegoat gesture only obliquely toward the mood and values of the artworks “under review.” Most evince the doomy political weather of the Trump era; stray references to dictators and totalitarianisms, hard corporatist landscapes, crushing hierarchies, systems of surveillance, so much casual violence. There are at least two allusions to nuclear disaster.

The more explicitly art-oriented fables proffer subtle meditations on originality, inspiration, and affect. There’s even a Proustian conflation of people and paintings (see Chardin, above). Many make me laugh out loud. In “On Not Being Able to Paint,” a painter casually pushes an acquaintance named Pascal—Pascal is a player in the sausage industry—from a balcony at the Ritz. His crime is uttering the words “frugal muse” in the painter’s presence: “I resented Pascal for thinking that my muse had been parsimonious.” The defenestrated sausage man splatters across the pavement, and Koestenbaum’s description of his carcass is luminous: “Pascal’s so-called limbs lay in a starfish pattern around him; they seemed, these flesh-sticks, to be still connected to his trunk, but they resembled spokes from a dismembered bicycle wheel or a wind-destroyed umbrella.”

“Plot is the disease!” said someone, I can’t remember who, on Twitter while I was reading these fables. Koestenbaum, I venture, would agree. None of these darkly comic tales submit to conventional architectures of storytelling. Characters come and go, do and say barely explicable things, their motives beyond our reach. I suspect the reader’s response will depend on one’s taste for textual coherence and willingness to go with the flow. Resist and you will be left frustrated, groping for meaning. But give in—admit that you’re living in preposterous, narratively scrambled, crookedly fabular times—and you may be richly rewarded.

Like some of his writer heroes—Donald Barthelme, Jane Bowles—Koestenbaum concocts exuberantly sui generis worlds. Narratives may be threadbare, or barely there, events curious or unfamiliar, but plausibility accrues as you go along, sentence after sentence. Some of the more memorable creations of this wild and prodigious imagination: a king of Nevada, a Sebald Sandwich (“tongue-with-horseradish-sauce”), a (male) curator at something called the International Gallery of Butterflies with a predilection for Diane von Furstenberg wrap dresses, a bisexual chandelier, and an ice-cream man with a “particularly green” penis named Edgardo (the man, not the penis). There is an abundance of sex, of all flavors (arcane, comic, murderous).

Koestenbaum’s imaginative magic extends to his sentences, sensuous and syntactically adventurous, rarely a means to an end but ends in themselves—bravura, permissive, frivolous. His lines make one’s own feel anorexic, dull by comparison. Like Gary Lutz, he believes that each sentence is an island; there are no pedestrian bridges, no handrails. Take this, from a fable called “That Odd Summer of ’84”: “I sank into the puce possibility of joining Persephone at the nail salon, where we could sit around and eat ‘failure chips,’ a new sage-and-lavender-scented snack, a feast rude and divagating as my masculine friend’s indigo-jeans-clad knee, its hunkiness too late for me to embrace.” Koestenbaum is the Claridge’s of language when we’ve become accustomed to settling for the austere comforts of the Budget Inn.

Write everything as if you’re writing a novel. That’s what Bruce Hainley, a critic and Koestenbaum devotee, told me he remembered the writer saying to him once. I’m not exactly sure what that means but it is seductive advice. In any case, this is not Koestenbaum’s first foray into fiction “proper.” He has written novels, 1.5 of them. Circus, originally published in 2004 as Moira Orfei in Aigues-Mortes, features a lapsed concert pianist who dreams of staging a comeback alongside the queen of the Italian circus. There’s also Hotel Theory (2007), half of which is a pulpy novel starring Lana Turner and Liberace, the other half a philosophical meditation on hotels as psychic spaces.

Koestenbaum’s intellectual restlessness, his aliveness to the world, reminds me of another of his lodestars. “Susan Sontag, my prose’s prime mover, ate the world,” he wrote in an essay for Artforum back in 2005. He eats the world, too, but his degustations are less crankily imperious than those of our lady of the skunk hair. In “Stein Is Nice,” an old essay on Gertrude collected in Cleavage: Essays on Sex, Stars, and Aesthetics (2000, but woefully out of print), Koestenbaum ponders the writer’s “perpetual flight from directness,” the fact that “she wrote without an audience, and she wrote against the idea of an audience.” He may as well be describing his own poetical esotericism. He concludes: “Stein is literature’s island of exemption—freedom from any rule that might interfere with the exercise of high caprice.”

Caprice may be the spice of life—or at least an antidote to the malaise that lingers in the backdrop of The Cheerful Scapegoat. “I bit into a caraway rye roll this morning and pretended it was Judy Garland’s talent,” says a gout-stricken character in “The Red Door,” rebuked for his appetites. Like nudity, another Koestenbaum fetish, indulgence is an oasis in the desert. For Koestenbaum, the human body is porous, lascivious, at times filthy—a utopic realm where hierarchies are flattened, where drool, spit, and spunk spill out of straight lines in an inexorable flow. One of the fables collected here is called “The Logic of Rivulets.” A manual for revolution? Why not? Communism in the streets, surrealism in the sheets.

Negar Azimi is senior editor of Bidoun.