SHE CALLED HERSELF a minor writer. “I’m no Tolstoy,” said this woman whose parents named her after a character from War and Peace. One wishes Natalia Ginzburg hadn’t apologized for her gifts. Wishes that she had luxuriated in her standing as one of Italy’s finest postwar writers. The fact that her various novels, novellas, and essays are flying back into print—some freshly translated—thirty years after her passing is not unrelated to the extravagant success of the other Italian, the one whose books have become the stuff of prestige television. Ginzburg, alas, has no HBO series attached to her name, but surely her estate profits from the fumes of Ferrante fever. As publishers scramble to chart distinguished genealogies of Italian women writers, we are invited to “discover” Ginzburg’s work in essays like this one. As though it had not been hiding in plain sight for decades.

If Elena Ferrante is a master of the sprawling, unputdownable epic, Ginzburg is a miniaturist. Her themes are buried in gestures, fragments, absences—not in what is said, but in what is not said. “Why is everything ruined, everything?” asks a character in the recently reissued 1961 novel Voices in the Evening. The nameless village in which the story is set smells like rotten eggs. This feels important.

The ruin, of course, is a legacy of the Second World War, the great disfiguring force that spreads across Ginzburg’s work like a fog, rarely addressed head-on, but hinted at, a hazy presence in the distance, a font of spiritual and material anomie. Stories are imbued with a jagged, melancholy air; protagonists feel dried up, broken, beaten down, their lives narrow and crumpled. “Something has happened to our houses. Something has happened to us,” she wrote in a 1946 essay called “The Son of Man.” “We shall never be at peace again.”

Who is this “we”? The archetypal narrator in a Natalia Ginzburg story is recessive, anemic, sketched rather than painted. A woman, she is often of marriage age but disastrously unattached, the prospect of spinsterhood dangling over her head like a scarlet letter. She is a student of literature or a magazine editor, a schoolteacher, an aspiring or former novelist. If she has been married, she is either widowed or ambiguously divorced. She is marginal to the action in the traditional sense, the wallflower at the dance, a keen but dispassionate observer of the parade of human life. Ginzburg’s friend Italo Calvino suggested that she is a stand-in for the author herself.

The women in Ginzburg’s fiction are thwarted by circumstance; life happens to them rather than the other way around. Few are exceptionally attractive; most are not attractive at all. Their ordinariness diminishes their options. We know that the central character of the newly reissued novella Borghesia—one of the few books Ginzburg wrote in the third person—once wrote a novel. Now a thin and wrinkled widow, she dreams of leaving the city, but mostly fills her days doing laundry for her antiques dealer brother-in-law and finds company in cats. This is nice, but bad things keep happening to the cats. “We’re really unlucky with cats,” says her daughter.

Here and elsewhere, Ginzburg’s abiding concern was family. “That is where everything starts, where the germs grow,” she once told an interviewer. Germs! Families in all their infectious glory and malaise are at the center of Ginzburg’s best novels, stories about square pegs and round holes, about family as an arbitrary if ancient system, a construct that lends forced coherence to lives that molder away inside.

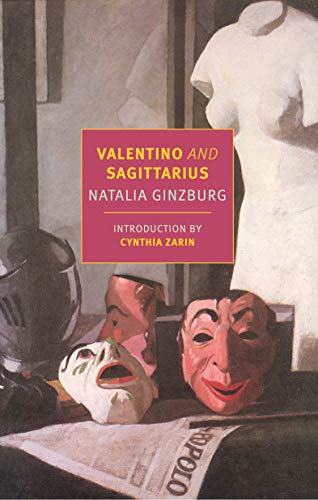

Her stories are strewn with disappointed parents. Who can blame them? Their heirs are lazy, they marry poorly, they’re bad with money. In the 1951 novella Valentino, a young man is spectacularly spoiled by his family, his father given to repeating the mantra that he will one day become a “man of consequence.” He becomes no such thing. Rather than studying for his medical exams, he plays with the cat, flirts with girls, and admires his own physique in the mirror while wearing a skiing costume. (He hardly skis, we learn from his sister, who serves as dispassionate narrator.) When he announces his intention to marry a mannish and mustachioed woman—she is “as ugly as sin,” but rich—his family is baffled. His mother weeps. The marriage is consummated, and proceeds to crumble.

It should be said that most of the men in Ginzburg’s fiction are lazy, noncommittal, and vain. They wear their imperfections like a tatty toupee. And yet for the longest time, Ginzburg wished that she could, in her own words, “write like a man.” Much has been made of what the legendary Italian journalist Oriana Fallaci once called Ginzburg’s “dry, virile style.” “I had a horror of anyone realizing from what I wrote that I was a woman,” Ginzburg wrote in an essay called “My Vocation.” She changed her mind after having children, concluding that her newfound knowledge of things like cooking and child-rearing only fed her writing. “New expressions were like a yeast that fermented and gave life to all the old words,” she explained. Later, she would propose a new maxim: “A woman must write like a woman but with the qualities of a man.” These qualities, she suggested, were a certain detachment and irony.

Her influence on other women writers is unmistakable. Faye, the oblique protagonist of Rachel Cusk’s Outline trilogy, owes much to Ginzburg’s narrators. (Cusk has credited Ginzburg with creating “a new template for the female voice.”) The critic Cynthia Zarin has compared Ginzburg to Grace Paley. Is there an echo of Ginzburg’s A Dry Heart, which opens with a woman shooting her husband in the face, in The Days of Abandonment, Elena Ferrante’s smoldering portrait of female rage? I’d say so. I see her wry humor and descriptive prowess in Gini Alhadeff’s writing, too. In gauging Ginzburg’s own influences, Calvino once named Chekhov and Katherine Mansfield, along with the Italian writers Grazia Deledda and Caterina Percoto. You could add Ivy Compton-Burnett and Muriel Spark to the list as well. Ginzburg herself mentions Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse.

Hemingway is rarely mentioned, but should be. As a young editor at the illustrious Einaudi publishing house, Ginzburg worshipped that most vexed icon of literary masculinity. Like the man with the beard, she was economical with words. Her sentences are matter-of-fact, remote, distinguished by their aloofness. News of a death is delivered in the same breath as what was served for dinner. Later in life, she would attribute this austerity to the facts of her childhood: “When you are the youngest in the family, people are always telling you to hurry up, get to the point, say what you mean. I think that’s why I write the way I do.”

NATALIA LEVI was born in Palermo in 1916 and raised in Turin, the youngest member of a family of radical bourgeois intellectuals. Her father, a Jew from Trieste, was a prominent biologist and professor of human anatomy. Her Milanese mother, a bubbly Proust-loving Catholic, was prone to impromptu opera singing and repeating stories ad nauseum. Ginzburg was only eight years old when Mussolini established Italy’s fascist dictatorship and from a young age she remembered her father’s socialist comrades being stashed away in the house.

According to her Italian biographer Sandra Petrignani, the young Natalia “wore unshapely shoes and an old trench coat” and spent hours locked in her room writing poems and smoking cheap cigarettes because she was “committed to poverty.” At sixteen or seventeen, she wrote these words: “Only by telling the truth can a work of art be born.” At twenty-one, she began her translation of Proust’s Swann’s Way, the first in Italian.

Her masterpiece—the hyperbole is warranted—is Family Lexicon, which won the Strega Prize, Italy’s most prestigious literary award, shortly after its publication in 1963. Ginzburg described it as a memoir that should be read like a novel. Though the specter of fascist Italy offers a grim backdrop, the book is a delight, in large part thanks to the cantankerous father figure at its center, Giuseppe Levi, who theatrically scolds his family for their endless crimes: being lazy, stupid, or ill-mannered, cavorting with unserious people, imbibing sugar, being, in his own words, morons, jackasses, and buffoons. “Nitwitteries!” he exclaims when frustrated, which is most of the time. The book is unforgettably percussive, its lingua franca the family’s distinctive verbal tics and stylizing. “Those phrases are our Latin, the dictionary of our past, they’re like Egyptian or Assyro-Babylonian hieroglyphics,” Ginzburg writes of their private patois. A meditation on memory among other things, it may be the most Proustian of Ginzburg’s books. It is also the funniest.

In 1938, Natalia married Leone Ginzburg, an Odessa-born literary critic with a large nose and bushy eyebrows whom she was wont to describe as intelligent, cultured, serious, and “ugly, very ugly.” (When Oriana Fallaci objected that he was handsome, Ginzburg smiled.) A translator of Russian literature—he translated Anna Karenina—he was also a leader of the underground anti-fascist group Giustizia e Libertà. The year they married, his Italian nationality was stripped away by the regime’s new racial laws. Two years later, he was banished to Pizzoli, a village in the mountainous Abruzzi region, where Natalia and their children would join him.

In Abruzzi, Natalia received a postcard from the novelist Cesare Pavese, a close friend. “Dear Natalia, stop having children and write a book that is better than mine.” She produced The Road to the City, her first novel, not long after, in 1942. Because Jews had been banned from publishing, it appeared under a pseudonym. Mussolini fell the following year and Leone and Natalia returned to Rome, where they posed as brother and sister and Leone joined the resistance to the ensuing German occupation. He was arrested in November of 1943 and dragged away to Regina Coeli prison, where he was murdered by Nazi forces. Natalia was twenty-seven years old.

“I never saw him again,” Ginzburg, the queen of the understatement, writes in Family Lexicon, making no mention of her husband’s grisly death, nor of the tortures—said to include crucifixion—that preceded it. “The pains never heal,” she told Fallaci, their encounter reducing the famously cold-blooded journalist to tears. In her profile of the author, Fallaci lingered over Ginzburg’s “masculine, sad face that looks almost as if it had been carved out of wood.”

AFTER THE WAR, Ginzburg worked as a translator and editor at Einaudi. She married again, this time to a professor of English literature named Gabriele Baldini, and had two more children—a son, who died before he turned one, and a girl, born handicapped, whom Ginzburg would take care of for the rest of her life.

Baldini, who was gregarious and dipsomaniacal, died of viral hepatitis in 1969 at the age of forty-nine. Ginzburg was only fifty-two, and would continue to be immensely prolific. She translated works by Flaubert and Maupassant. (The influence of the latter is especially evident in the recently reissued novella Sagittarius, the story of an ambitious woman’s dreams gone awry.) She wrote plays, some of which became famous, including one called The Advertisement that would be codirected by Laurence Olivier in London. A novel, Caro Michele (translated as Happiness, as Such in English), became the basis for a popular Italian movie. A close friend of Pasolini’s, she acted too, making an appearance in The Gospel According to St. Matthew as Mary of Bethany, the sister of Lazarus. (A young Giorgio Agamben plays Philip the Apostle.)

In her sixties, she served two terms as a Leftwing Independent parliamentarian. Among her notable political positions, she campaigned for Palestinian rights. At the end of her life, her household included her disabled daughter, Susanna, her daughter’s caregiver, and a young Palestinian girl named Rasha Taher. The hodgepodge families Ginzburg wrote into her stories echo their creator’s own uncommon family arrangements.

When there are glimpses of happiness in Ginzburg’s work, they take root in unlikely places, outside the narrow confines of convention. Voices in the Evening, set in the period immediately after the war, is a portrait of the children of a factory boss as told by Elsa, the factory accountant’s daughter, a typically opaque Ginzburgian narrator. Elsa is having a covert love affair with Tommasino, the youngest of the boss’s children, and the pair meet every Wednesday in a modest rented room. Ginzburg sketches the parameters of their relationship with typical precision, through an accretion of specifics that accumulate incredible force, humor, and beauty.

Tommasino and I met every Wednesday in the town.

He waited for me outside the “Selecta” library. There he would be in his old overcoat, a bit shabby, his hands in his pockets, leaning against the wall.

He would greet me, bringing his hand to his forehead and taking it away, with a languid smartness.

We only saw one another in the town. We avoided meeting in the village. He wished it so.

For months and months we had been meeting in this way, on Wednesdays, often on Saturdays as well, and we always did the same things; we changed the book at the “Selecta” library, bought some oatcakes, bought also for my mother fifteen centimeters of black grosgrain.

Then we went to a room which he had hired in the Via Gorizia, on the top floor.

The room had a round table in the middle covered with a piece of carpet, and on the table was a glass cloche which protected some branches of coral. There was also a little stove behind a curtain where we could make coffee, if we wanted to.

He said to me sometimes,“See, I am not marrying you,” and I would laugh and say, “I know that.”

He said, “I don’t want to marry; if I did, I should probably marry you.”

And he would add, “Is that enough for you?” and I would say, “I can make it do.”

Later, for no particular reason—inertia or boredom or weight of convention—Elsa suggests that they get engaged, and Tommasino agrees. Their relationship goes to pieces. They’re both unhappy. The freedom they experienced with each other in that anonymous space, it turns out, cannot survive exposure.

My favorite of Ginzburg’s unusual entanglements is the subject of her 1977 novella Family. A depressive architect named Carmine is married to Ninetta, a shallow upper-class woman whose company leaves him feeling “numb and cramped.” He reconnects with Ivana, a long-ago lover, and soon begins spending his evenings with her and her teenage daughter, Angelica. The routine assumes the contours of ordinary family life; Carmine reads the paper, he and Angelica play chess, sometimes he looks up words in the dictionary for Ivana, who makes a living as a translator. A young homosexual with a speech impediment named Matteo Trammonti occasionally passes by to round out this unconventional family. Late at night, Carmine goes home to his own wife and child.

Ivana and Carmine no longer remember why they left each other in the first place; it hardly matters. We learn at some point that they had a child, and the child died. By the end, as Carmine succumbs to a terrible illness, it’s the thought of his makeshift family that brings him peace. He remembers a summer day they had once spent at the cinema:

Thinking back on that Sunday, it seemed like a very nice day, and yet, he had not noticed it at the time, because there was nothing wonderful about going to see a bad film, nor about sitting in a café, ordering ice-creams and waiting for the evening to come. He felt an agonizing nostalgia for that day now, and yet, they had been bored sitting in that café, thinking they would spend thousands more days like that one, just as they had done in the past, because there was nothing so easy and mindless sitting in a café for a few hours.

Carmine’s reverie echoes Ginzburg’s own reflection in “Winter in the Abruzzi,” an essay she wrote about her years of confinement with Leone and the children, which she came to consider “the best time of my life,” despite everything. Or because of it: “Only now that it has gone from me forever—only now do I realize it.” This is, she says, an “ancient and immutable” law, that “the instant [our dreams] are shattered we are sick with longing for the days when they flamed within us. Our fate spends itself in this succession of hope and nostalgia.”

But there’s space for something else, outside the cycle of illusion and disabuse, a kind of grace shot through with calamity. In her conversation with Fallaci, the journalist noted that some of Ginzburg’s friends had suggested that the writer might be secretly happy—that joy had the power to overcome pain. (As her son Carlo once observed, of the mother rather than the writer, “She was great fun.”) Ginzburg pushed back. “No,” she said. “I believe that happiness is achieved through pain . . . that pain and happiness are intertwined.” Fallaci completed the thought. “Then she’s serene. Not happy: serene.” Serenity, then.

Negar Azimi is editor in chief of Bidoun.