ON DECEMBER 25, 1991, Gorbachev appeared on snowy televisions in the homes of millions, gray faced against gray wallpaper, to resign as the leader of a state that no longer existed. He handed over the keys and a briefcase full of nuclear codes to Yeltsin, and the red flag was lowered. George Bush Sr. quickly got camera-ready on Christmas, addressing the American people, “During these last few months, you and I have witnessed one of the greatest dramas of the twentieth century.” The Soviet Union was over, but the year was ending on a cliffhanger. Cut to January 2, 1992: as the hangover of a momentous New Year’s was starting to loosen, families in Moscow gathered to watch episode 271 of a struggling American show, Santa Barbara, the first foreign soap opera to be televised in Russia. It was a repeat, to say the least; the season had been filmed and shown in the United States seven years earlier, but this time warp was not a surprise or a deterrent. The show, with two-thousand-plus episodes, would become the longest-running television series broadcast in Russia, ever. Santa Barbara, as a narrative form, distant location, and cloudless fantasy, became a craze of the highest proportions, spurring pop songs, pet names, even copycat architecture across the former USSR.

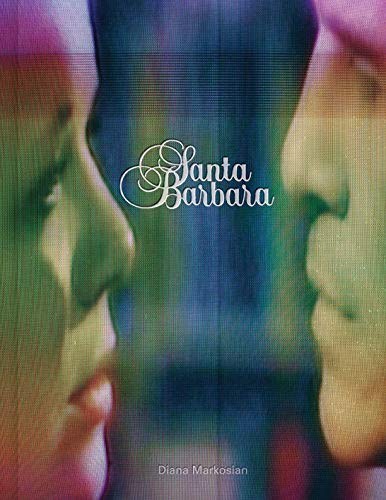

The photographer Diana Markosian was three years old, living in Moscow, when Santa Barbara first aired, and her mother, Svetlana, was a devout viewer, alongside millions of other Russians. In her new monograph, Santa Barbara (Aperture, $65), a collection of photographs and ephemera that were exhibited with a short film of the same title, Markosian restages her mother’s tumultuous life through the prism of the show, which irrevocably altered her entire world. In the years after the collapse of the Soviet Union, Svetlana’s marriage followed suit; her husband, Arsen, a former engineer who survived by selling black-market Barbie outfits, left her and their children for another woman. Svetlana struggled to feed her family, and when Diana was seven years old and her brother eleven, she packed them up for an unexpected trip. The young mother and bleary children arrived in California, where they were met at the airport by a much older, large American man who was introduced as their new father. They never returned home. Unbeknownst to her children, Svetlana had met the man through an international matchmaking catalogue. Out of many responses to her ad, she had picked Eli, who promised stability, if not true love, because he lived in the namesake city of her favorite TV show.

Markosian commissioned Lynda Myles, one of the original Daytime-Emmy-Award-winning screenwriters for the soap, to script Svetlana’s memories in the style of Santa Barbara, and the text, monosyllabic and heavy on exclamation points, helpfully narrativizes the photographs in the book while also tracing the bitter limits of such a narrative. An actress named Ana Imnadze, keenly sorrowful and equally cheek-boned, and the surprisingly empathetic Gene Jones play the married strangers in Markosian’s reenactment, which follows the family from a bleak Moscow apartment to a Palm Springs honeymoon and through an eight-year marriage. It’s a lot for one episode, but Markosian is clearly invested in the long scrape of horizon, the oceanic proportions of a single decision, the unforeseen outcomes of fictional worlds.

In his 1988 book America, Jean Baudrillard writes, “Santa Barbara is simply a dream and it has in it all the processes of dreams: the wearisome fulfilment of all desires, condensation, displacement, facility of action. All this very quickly becomes unreal.” How does it feel to come to the truth of what was once a fantasy? Back to earth, bodies reassert themselves, vulnerable as ever. Unsurprisingly, Markosian hovers over scenes of food: her mother in a huddled crowd bargaining for bread; her first father offering a morose, flattened birthday cake, candles burning down at different speeds; a full supermarket cart pushed by her second dad, the visual shriek of Lucky Charms packaging. Excess and deprivation lace the uncertainty of the American marriage. The photographs can become a little repetitive when Markosian relies too much on the contrast between Svetlana’s beauty and Eli’s aging body (just one or two Death and the Maiden tableaux would have made the point). The risk of overstatement, however, only underlines the project’s central premise, which is the commitment to artifice as an emotional territory: a place one can visit, maybe even live in. The work is at its best when it implicates its own aesthetic, heavy shadows and beseeching expressions, in the creation of another fantasy. At times, Markosian’s visual style evokes the pantheon of late-twentieth-century photographers who reveled in the secret theatricality of the American mundane, the saturated nook and cranny: Gregory Crewdson, Stephen Shore, Larry Sultan, and Justine Kurland, among others. Many of them have since become synonymous with the kind of mythic Americana they originally interrogated, further complicating Markosian’s frame of reference. And yet, despite my own personal skepticism of authenticity—or subtlety, for that matter—the most moving photographs for me were probably the least staged: Markosian’s portraits of Santa Barbara itself, hidden behind a wet, blunt curtain of fog. Her sky and ocean mirror nothing but gray back to each other. Her palms and bougainvillea are buried in the haze of the marine layer, tinged with a sickly blue or streetlight yellow. It must be June.

When I say overstatement, do I really mean kitsch? This is Soviet grief filtered through daytime melodrama with a side of the American dream, after all. I like to think irony about irony is like dividing by zero, but I had to repeat algebra three times. Santa Barbara (the show) didn’t take with American audiences as well as competing soaps of the era—compare its two-thousand-odd episodes with All My Children or The Bold and the Beautiful, now in the eight-thousand-to-ten-thousand range—which Myles, in a short essay included in the book, suspects might have been because of its “actively cultivated” humor and “tongue-in-cheek sensibility.” It was a melodrama that, sadly, knew itself as such. At first glance, it all seems pretty standard: the show tracks the various crimes, romances, and revenge plots of tanned businessmen and their adjacent heiresses, with sleeves like iridescent coffee filters and names like Flame Beaufort or Laken Lockridge. But the creators of Santa Barbara prided themselves on embracing the soapiness of the opera at hand: one of the most famous scenes depicts a pregnant ex-nun, who has been raped by her husband, telling her lover that she doesn’t know who the father of the baby is, on the roof of his eponymous hotel, when suddenly the Santa Ana winds dislodge the bolts of the hotel sign, and a giant “C” falls on her, mid-monologue. She is crushed to death by the name of the father. It’s Sirk, but without any subtext.

Some of the distinctive features of soap operas are their constitutive endlessness, their lack of a main character, and their complete disavowal of rationality. These are also features of most families. In Markosian’s Santa Barbara, one father is exchanged for another, as if no one will notice. In true soap-opera fashion, the actor may change, but the role remains the same. The children, or audience, can be trusted to play along with a new face at the head of the table, to suspend their disbelief in the strange rituals of paternity. The reenactment of Svetlana’s marriage, directed by her grown daughter, emphasizes the theater inherent in so many domestic arrangements, how much imitation and compromise are required to reach an economically sustainable femininity, a livable motherhood, especially in the face of political crisis. Just as Svetlana was picked out of a catalogue, old men line up to audition for the role of husband and father, hoping to be picked by Markosian. Their headshots, side by side at the end of the book, mirror the images of young women with newsprint smiles at the beginning, in search of a husband who is also a passport. In layering performances, Ana playing Svetlana playing Santa Barbara, Markosian allows the viewer to move between fantasy and reality, agency and exploitation, belonging and loss, without much distinction. When Ana, the actress, asks the real Svetlana if the real Eli is still alive, fourteen years after they last saw each other, Svetlana says she doesn’t know, and she doesn’t want to know. “For me, he is alive,” she answers. In soap operas and dreams alike, no one ever really dies.

Audrey Wollen is a writer from Los Angeles, living in New York City.