Audrey Wollen

Before dawn on January 9, 1800, a young boy emerged from the bare winter forests that surrounded a small village in southern France. A local caught him pulling out vegetables from a terraced back garden, naked except for the tatters of what was once a shirt. He was hungry, dirty, self-assured, and silent. The thick […]

IN HER RECENT BOOK WAVE OF BLOOD, Ariana Reines states the obvious: “It’s a big mistake to kill someone, one person, one person.” I pause on the word “mistake” there. An odd word: pared down, it means “to badly seize,” to reach out and wrap your fingers around a reality that is incorrect. It describes […]

LET US START at the end, though it might feel strange at first: “Dugong.” That is the entirety of a one-word story by Joy Williams, also titled “Dugong,” which closes her new book, Concerning the Future of Souls. A dugong is a marine mammal of impenetrable placidity; also called the “sea cow,” they spend most […]

IF THE TITLE of Helen Garner’s 1984 novel, The Children’s Bach, could strike a chord, it would be a diminished seventh—an unexpected tone of dissonance, curling toward the uncanny, eager for resolution. The title is borrowed, as chords often are, from a 1933 collection of Bach’s easier pieces, edited by E. Harold Davies and still in print. The instructional text telescopes into the novel: Garner’s character Athena is learning to play piano, pinched by determination in the absence of natural talent, no longer the hypothetical child of Davies’s intent. She is the mother of two sons, home for long afternoons as

AT FIRST, TINKERBELL WAS ONLY A LAMP, a small mirror, and someone crouching in the dark. He tilted his wrist to make her fly, shimmering light. A bell was her voice and applause was her medicine. In 1904, she promised children that belief was enough, ritual worked, and friends could come back from the dead. “Never” was a land, a country. If you were an eight-year-old boy in that London theater, clapping for Tink, odds are you were deep or dead in the trenches ten years later. Loss dug itself into towns, steady and chasmal, leaving old men, women, and

THE FIRST HALF of Patricia Lockwood’s novel No One Is Talking About This opens in a place between life and death. The second half unfolds in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. The first half is about the internet. The second half is about having a body in a world. These halves are as discrete as a clunky little screen glowing its gloamish light into an open face, two limitless modes that find their limit only where they merge. The novel takes shape in the parenthetical scoop of a Venn diagram between machine and mind, crowd and solitude, joke and beauty.

ON DECEMBER 25, 1991, Gorbachev appeared on snowy televisions in the homes of millions, gray faced against gray wallpaper, to resign as the leader of a state that no longer existed. He handed over the keys and a briefcase full of nuclear codes to Yeltsin, and the red flag was lowered. George Bush Sr. quickly got camera-ready on Christmas, addressing the American people, “During these last few months, you and I have witnessed one of the greatest dramas of the twentieth century.” The Soviet Union was over, but the year was ending on a cliffhanger. Cut to January 2, 1992:

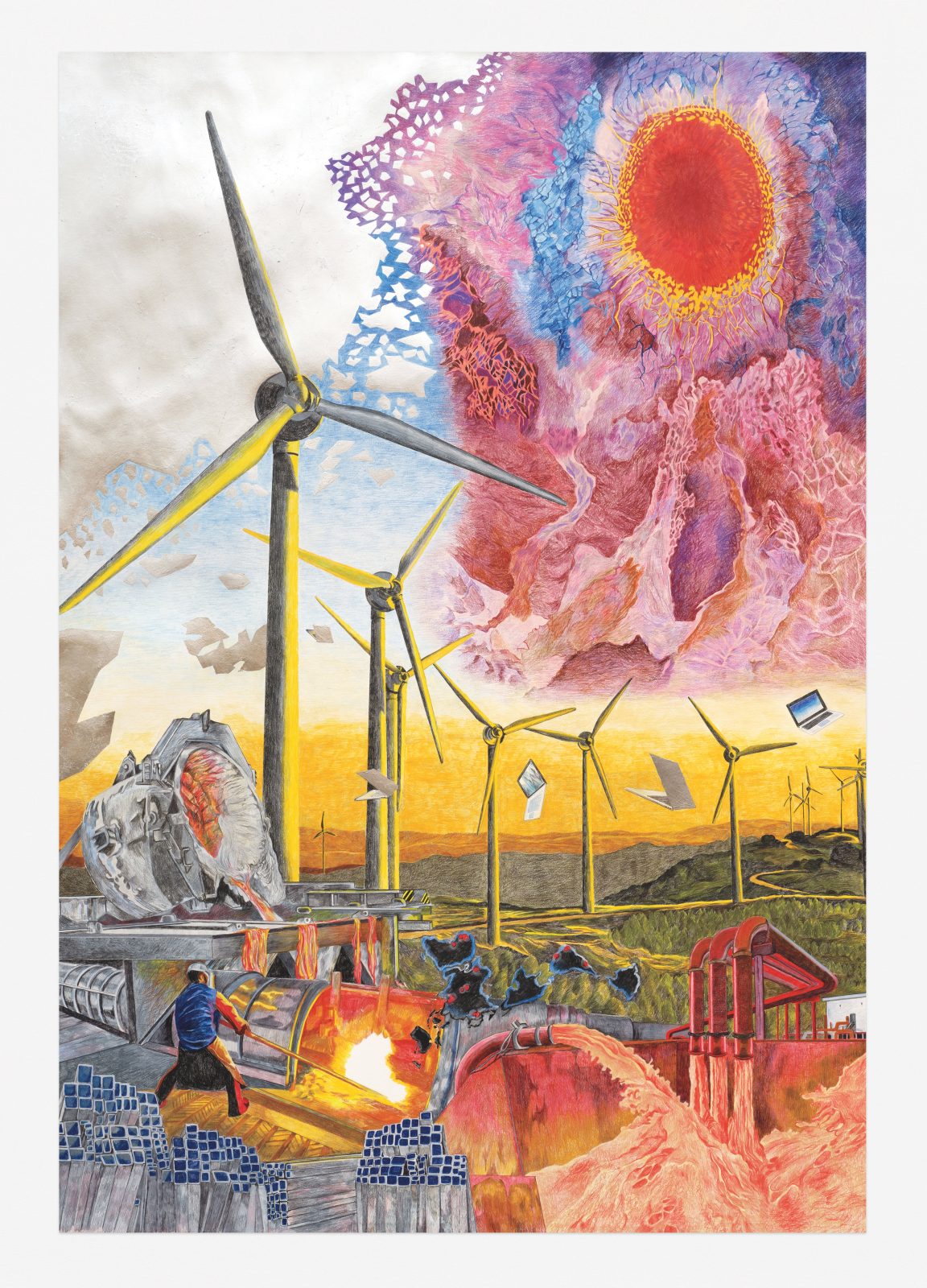

MY FRIENDS’ FACES are hovering in a line of small, burnished tiles. Each square looks alive in a miniaturized way, its own gestural universe, flickering and reflective like sequins from the hem of a dress. We are discussing the end of the world, which means, for us, the fortunate, the end of our habits, the necessitation of new ones. We talk about science, swapping scraps of data with the fervent authority we previously reserved for gossip. “Well, I heard . . .” We talk about ventilators, a new finite resource. There were already so many finite resources, it’s odd to

No one could decide how to kill Helen of Troy. It’s a glaring oversight for such a crucial character. Greek tragedy is a genre that usually relishes any opportunity for a specific and harrowing death, especially for women—deaths that spill symbolism in shining pools. A woman’s way of dying is the apex of her meaningfulness: Antigone hanging herself in captivity, Clytemnestra stabbed by her own son, Polyxena sacrificed on the tomb of Achilles. It is strange, then, that Helen ends up without an ending. Not least because, according to the logic of the form, she should be the object of

Ali Smith is writing the world as it happens. In the vein of Charles Dickens, she has set out to reshape the serial form in her Seasonal Quartet of interwoven yet stand-alone novels, responding to the times, not in a mode of reflection but immersion, publishing as she goes. And what times to choose: best of, worst of, as it goes. To say that these have been eventful years, particularly in Britain still in the tenebrous haze of Brexit’s implosion, is beyond understatement. And yet Autumn (2017) and Winter (2018) both circle these political ups, downs, and side to sides