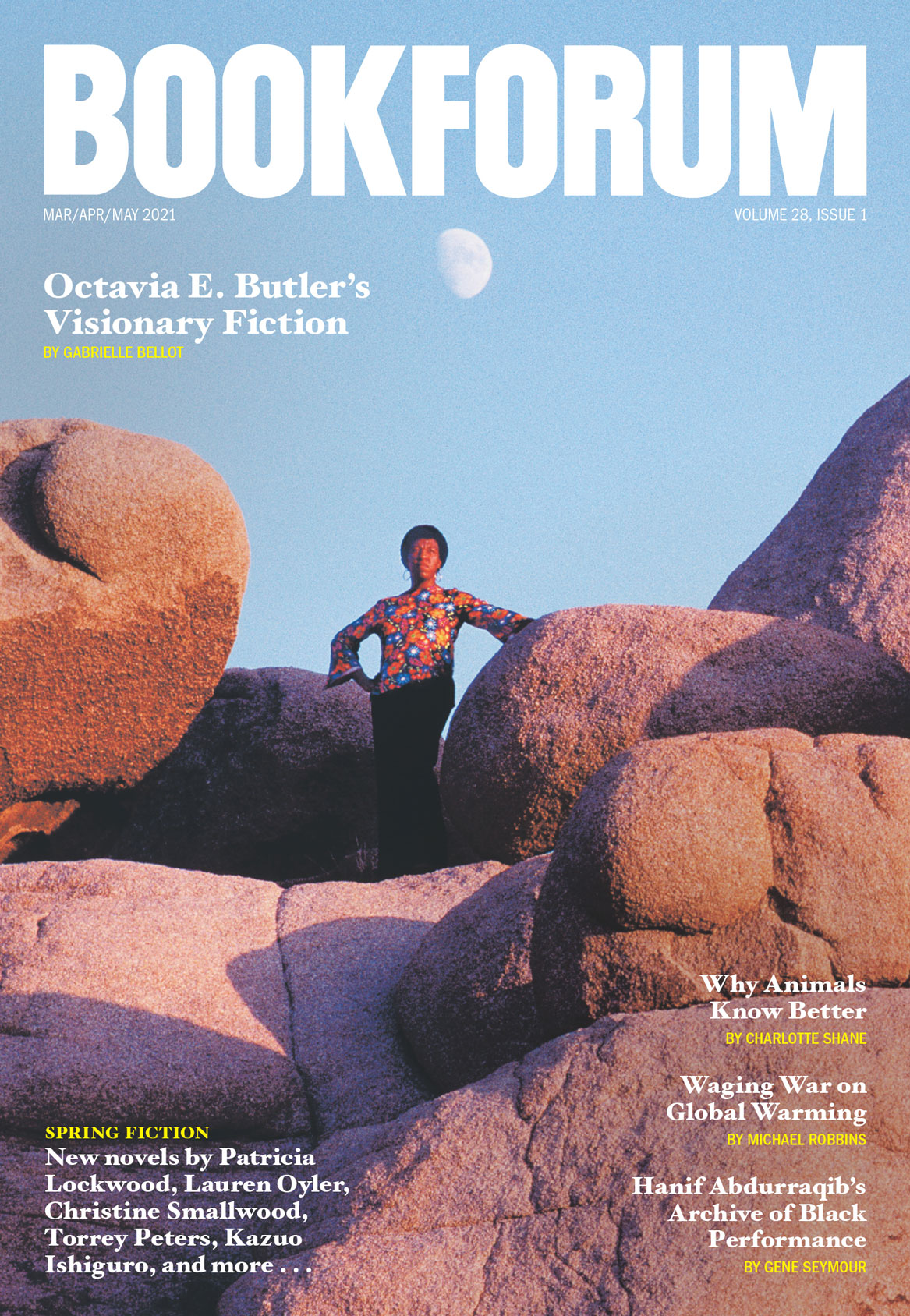

THE FIRST HALF of Patricia Lockwood’s novel No One Is Talking About This opens in a place between life and death. The second half unfolds in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. The first half is about the internet. The second half is about having a body in a world. These halves are as discrete as a clunky little screen glowing its gloamish light into an open face, two limitless modes that find their limit only where they merge. The novel takes shape in the parenthetical scoop of a Venn diagram between machine and mind, crowd and solitude, joke and beauty. A very online woman, unnamed, microfamous for the sentence “Can a dog be twins?,” is revealed to the reader through the vast landscape of her internet presence, the hills and valleys she traverses, the strange characters she meets along the way. Her husband, her family, her job, her friendships, her sexual desires, her political beliefs, everything about her is a tangential planet orbiting the gravitational force of “the portal.” At first glance, the plot follows a kind of reverse epiphany, where knowledge, or more precisely, information, is suddenly sucked out, falling through a trap door in a spaceship, pulled into the cosmic exhale of acute experience. Whoosh! Goodbye invisible engine of answers! Goodbye tinny birdsong of opinion! Goodbye unfurling archive of strangers! And most of all, goodbye image, image, image, image, image! Here is a baby. Here is a grave. Here we are.

Lockwood splits her novel down its center but never severs the connection between the two parts, like strands of river knotted at the same source. She says goodbye, but nothing leaves. Our narrator logs off, but without the simplicity that the phrase promises. I read the first part aloud to my mother as we lay next to each other in my bed through a heartbroken December. They were weird sentences to say to her, because much of the first half is about memes. For me—a person born in 1992, who has tended to some form of social media continuously since I was in elementary school—it constituted a library of the classics. Most fragments sketched a familiar object, lit up a pang of recognition. Oh yes, I remember that day, I thought to myself. I remember the day we talked about that online. For my mother—a person born in 1954, who sometimes types out descriptions of the emojis she would like to use instead of peering through the visual menu, signing her texts with the impossibly sweet string of words “twinkling star little sprout pink heart cup of green soup”—much of it read as absurdist fiction, the edge of late-breaking imaginations. As I read to my mother of spray-painted garage doors, emails to wives, relatable tree frogs, the corpse of infant Hitler, hotel mini-muffins to commemorate 9/11, she closed her eyes and pictured her own version of the internet. I thought about showing her, trying to explain. I’m not sure what reading this book would be like if I didn’t understand most of the references. But, of course, this is what novels do: I can read about a place I have never been, while others are reading about their hometown. The words are the same, and what they mean is different.

Writing about being online is a bit like writing about reading a novel, in the sense that it is language in concentric circles, description like ripples in a lake, or a bisected tree trunk. One imagines somewhere in the unseeable center there is a pebble, an ax: a real life. Maybe this is why writing a novel about being online is so difficult, as writers get stuck on an outside ring, or imagine themselves to be the projectile, the whetted force of the physical, rather than attempting to write about the entire radius of possible feeling. All of us know the cringe of trying to move the internet into another form: the flop of trying to repeat a viral joke in conversation, the small terror of someone saying, out loud, at a party, “I saw your Twitter . . . ,” the awkward nihilism of alt lit, the total failure of academic theory to corral the freaky corners of what goes on. It feels impossible to write down what was funny or beautiful on the internet. Iykyk. So, yet again, we are under the thrall of the unrepresentable. Our lives revolve around a huge secret that everyone already knows. As if sex, death, and the interdependent web of all existence weren’t enough! But Lockwood not only follows the circles out to their youngest brim, she also returns to the point of contact that set them in motion, and then she pushes it further: not the ax, but the seed. I think she pulls it off partly because she is not trying to write about what the internet is or does, but how it feels. She has managed to write a book about how it feels to be online, how “the hot reading did not just pour from her but flowed all around her,” but also how it feels to not be able to write about how it feels to be online, “arms all full of the sapphires of the instant.” The book is also about how it feels to speak to a baby while the baby dies and how those words are different from and the same as the ones we use to write. Ultimately, No One Is Talking About This is a stunning record of the hollows and wonders of language itself.

A lot of it, necessarily, is very funny. Not since Lorrie Moore’s “People Like That Are the Only People Here” has writing about sick babies been so funny. Lockwood is known for her jokes—in fact, she stepped into public attention with a viral poem, “Rape Joke,” which is what it sounds like and also isn’t. Her memoir Priestdaddy and her criticism for the London Review of Books are brilliantly precise, with a kind of comedy that is often truly surprising, almost chaotic. Reading her metaphors is like watching someone pull out a scalpel and cut the cleanest line you’ve ever seen, and then in the next sentence throw the knife over her shoulder with her eyes closed, grinning. To give the impression of the deeply random, of course, is a craft skillfully honed over decades spent putting sentences online. An old man accuses our narrator of internet nonsense; “‘It’s not nonsense! It’s folk art!’ she hollered back. Like those early American women who painted kids with enormous foreheads, either because they didn’t know how to paint regular foreheads or because it was a stylistic choice!”

Chaos begets chaos, which somehow will beget coherence. “One day it would all make sense! One day it would all make sense—like Watergate, about which she knew nothing and also did not care. Something about a hotel?” There’s a lot of exclamation points. She feels herself sinking further into the joke, the joke like a rising tide: “Already it was becoming impossible to explain things she had done even the year before, why she had spent hypnotized hours of her life, say, photoshopping bags of frozen peas into pictures of historical atrocities.” Sometimes it seems like all the promises of answers, information, and ease that technology asserts have to be balanced out by us, as if we are defiantly compelled to insert the inexplicable back into the explaining machine. Maybe that’s why what is funniest online is usually what makes the least sense. You could say poetry does the same thing to the explaining machine of language; some senselessness makes beauty instead of jokes. Or maybe that’s just what foreheads were like back then. Maybe this is all just what it’s actually like.

The moments of nonsense that Lockwood stretches wide can start out very small. In fact, the tinier the disruption, the better: the narrator struggles to pinpoint why “sneaze” is funnier than “sneeze,” why “binch” is funnier than “bitch.” The typo is a small flicker of physical interference, a gleam of failure. Of course, then we mimic, repeat our mistakes, slip our fingers on purpose, jam intonation into voiceless boxes, replace the word with its strange copy. Specificity rolls in and out, like a fog:

It was in this place where we were on the verge of losing our bodies that bodies became the most important, it was in this place of the great melting that it became important whether you called it pop or soda growing up, or whether your mother cooked with garlic salt or the real chopped cloves, or whether you had actual art on your walls or posed pictures of your family sitting on logs. . . . You were zoomed in on the grain, you were out in space, it was the brotherhood of man, and in some ways you had never been flung further from each other.

Other people are a mirrored hallway, expanding and narrowing the individual, doubling and doubling, cornering and cornering. “Strange, how the best things in this floating sphere seemed to have been written by everyone. There was no use in saying That’s mine to a teenager who had carefully cropped the face, name and fingerprint out of your sentence—she loved it, the unitless free language inside her head had said it a hundred times, it was hers. Your slice of life cut its cord and multiplied. . . . No one and everyone. Can a [blank] be twins.”

When the narrator’s mother texts her that something has gone wrong with her sister’s pregnancy—her younger sister whose life is “200 percent less ironic than hers,” who walked down the aisle to “The Imperial March,” whose love is unconditional—the narrator slips through the mirror, like Alice, into another world: “She fell heavily out of the broad warm us, out of the story that seemed, up till the very last minute, to require her perpetual co-writing.” The doctors tell them that “everything that could have gone wrong with a baby’s brain went wrong here.” It’s not clear if the baby will live, live for long, live in a way that we usually understand life to be: “The error was in an overgrowth pathway, which meant that what was happening to the baby could not and would not stop. . . . Inside her mother she was a pinwheel of vigor, every minute announcing her readiness.” Lockwood moves through all the realities of her characters with a spacious honesty. No doctor, no social worker, mentions the option of abortion, but they apologize, they weep, they tell the sister to “go out running and see what happened,” they make no promises, they say “the worst seven words in the English language. There was a new law in Ohio.” They can’t induce a pregnant woman before thirty-seven weeks, even if her life is in danger. The narrator promises to drive her sister across state lines, if she needs. The narrator promises everything, anything. Suddenly, the question of shared reality is vital, burning.

The sister prepares to give birth and grieve. Hospital employees gather to take photographs of the few seconds before the baby dies. “But she didn’t, and she didn’t, and then she unfurled like a wet spring thing and was alive.” She cries, and it is a kind of knowledge. Lockwood’s writing rises to meet the scene, dawning sentences, new and gold. What follows is six months of life, six unpromised months. And just like that, the wavy edge of language grows bigger, moving outward from another new person, another way of being specific: “All the worries about what a mind was fell away as soon as the baby was placed in her arms. A mind was merely something trying to make it in the world. The baby, like a soft pink machete, swung and chopped her way through the living leaves. A path was a path was a path was a path.” Data genuflects before the unknown: “All day she drank in information, but no one was telling them the main thing. No one was telling them how long they would have her, how long the open cloud of her would last.” The first half of the book—the entire raucous instrument of the portal—now reads like an elaborate cover-up, a decoy to distract from that blank space in its center, that “main thing.” It clicks with a kinetic frenzy, it whirrs and crunches, in contrast with the shiver, the heave of the second half. Maybe we need every answer in the world to survive a single question: How long do we have each other?

Caring for a newborn is hard and caring for a dying one makes the word “hard” seem small. Lockwood includes the granular constraints of a day, the logistical hurdles, the guttural exhaustions: how the banal presses down against the heightened reality of illness. This is the United States, so the bills pile up, reach the ceiling. When they can leave the hospital, they take the baby to Disney World. They are all still part of a world, Disney-ed or otherwise, a generation, with its own way of joking, its own way of grieving. There’s a robot in their house that records all their conversations and answers all their questions, Trump is still president, and they still think in tweet format. On the last day,

she curled up in the hospital bed next to the baby. She held the little hand and waited for its wilted pink squeeze, like the handshake of a lily. . . . She leaned over the child and said something; she said, “It is going to be just like your mother.” The moment was so pristine and so meaningful that something must be done to alleviate it, so she picked up her phone and began scrolling through Jason Momoa pics, all the while thinking, bitch if this even happens while you were looking at Jason Momoa pics?!?

Somehow, Lockwood includes references to Pure Moods commercials, GIFS of the Grinch, and a concrete goose dressed in seasonal outfits in one of the most heartbreaking death scenes I have ever read. A death scene that removed something from me, an excision, and then a gift: I felt grateful to know it. All I wanted ever again was knowledge just like that—that quiet halo of witness. But, afterwards, as I returned from the book, all of our languages seemed lit from within, stark and precious: “No vehicle ever invented for the transmission of information—not the portal, not broadcast radio, not the printed word itself—was as quick, complete, or crackling as the blue koosh ball that the baby kept tucked against her chin as she slept, her small mouth open to say oh my answers. Her other hand she kept twisted in a bright red pom-pom, believing it was her mother’s hair.” We ripple out, and meet each other, in pom-poms, in portals, in novels, in song. One day it would all make sense, says the language, laughing.

Audrey Wollen is a writer from Los Angeles, living in New York City.