WHILE WANDERING AROUND the Jewish Museum’s haunting exhibition “Louise Bourgeois, Freud’s Daughter,” curated by the artist’s former literary archivist Philip Larratt-Smith, I stopped at a melancholy sculpture called Ventouse, 1990, a double-decker hunk of hacked, chipped black marble that resembles a sarcophagus. The coffin is topped by protruding glass cups, their rounded ends lit from within by electric bulbs.

For some reason, while studying this sculpture that’s heavy in every way (after all, it is part of a show of Bourgeois’s psychoanalytic art and texts), I couldn’t stop thinking about another work with an opposite vibe—Yayoi Kusama’s lighthearted Narcissus Garden, 1966/2021, a pool of water filled with giant reflective balls that gently bounce from shore to shore, now part of the exhibition “KUSAMA: Cosmic Nature,” curated by Mika Yoshitake at the New York Botanical Garden. What could two such different works have to do with each other? In a word, balls.

Kusama’s Narcissus Garden and Bourgeois’s Ventouse both feature gleaming globes on flat surfaces. And both, I believe, come from a similar place—the land of daddy complexes and phallic fetishes. (I’m not the first to notice some parallels between Kusama and Bourgeois; in 2017 Sotheby’s S|2 gallery in London presented a joint show, as did Peter Blum Gallery in 2001.)

The biographical parallels are pretty stunning. Both girls’ fathers cheated on their mothers, and both girls were cast into their parents’ marital maelstroms. (Kusama’s mother demanded she spy on her wayward father; Bourgeois cared for her ailing mother in southern France while her father cavorted in Paris with her English tutor.) Both were smart, strong-willed, sensitive, and ambitious girls from prosperous families whose wealth came from their mothers’ side. Both were involved in their family’s work. (Kusama, born in Matsumoto, Japan, in 1929, spent time in her family’s seed nursery, which is where she had her first hallucinations, of talking flowers. Bourgeois, born in Paris in 1911, worked in her family’s tapestry-restoration business, drawing in the missing feet of the figures on worn-out textiles.)

Both girls were discouraged from making their own art. (Kusama’s mother ripped up her drawings; Bourgeois’s father derided her work.) Both artists attempted suicide and both tried poetry and psychotherapy. (Kusama saw a psychiatrist for her hallucinations and once checked herself into a psychiatric hospital; Bourgeois pursued a long psychoanalysis for depression.) Both es-caped their families by moving to New York. (Kusama came by herself in 1957, with an encouraging note from Georgia O’Keeffe; Bourgeois came in 1938 with her husband, the art historian Robert Goldwater.) Both faced their demons by making phalluses.

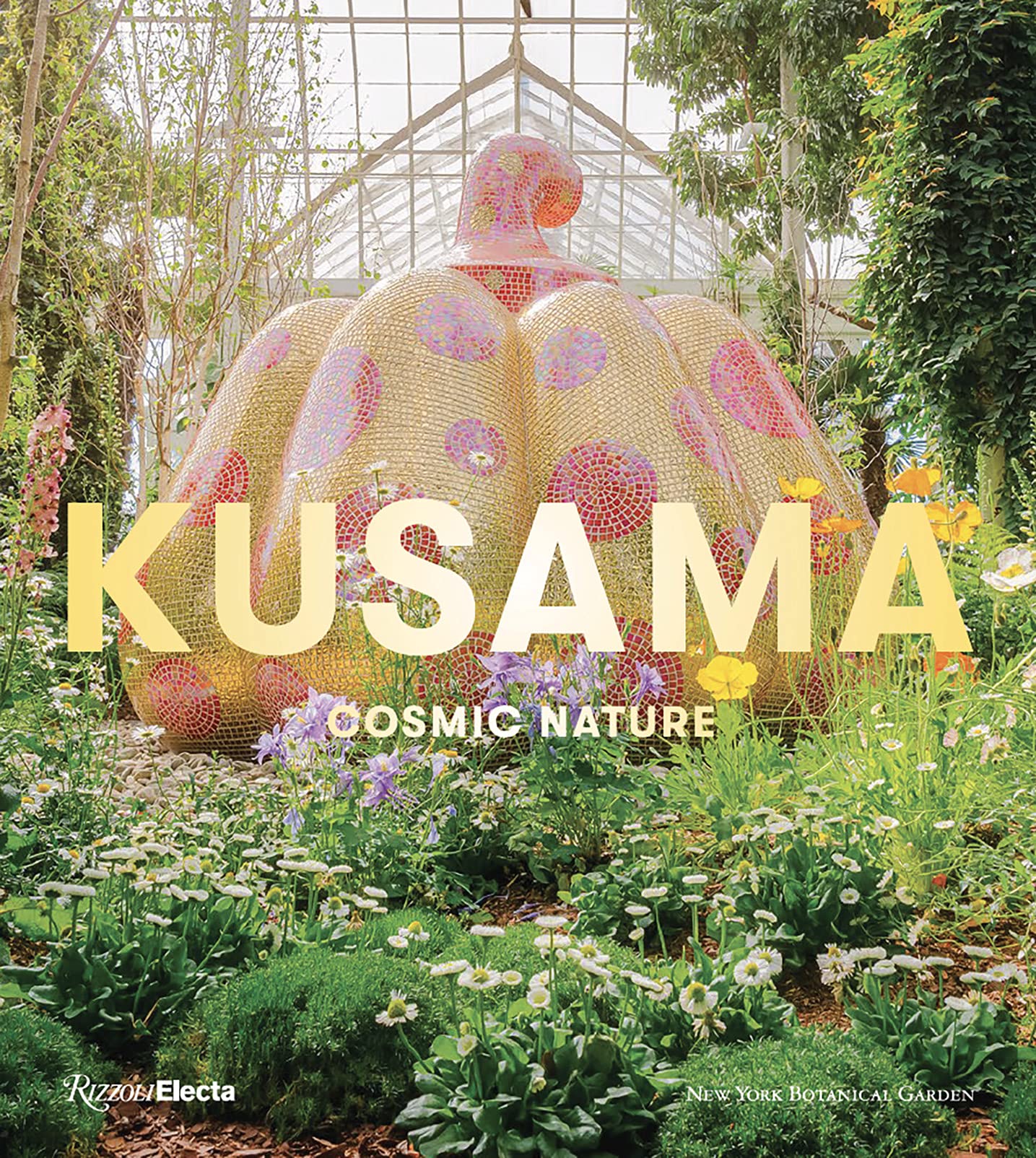

Two sets of books help make the case, when taken together, that these two artists shared one more thing: the peculiar phallic objects they made were precisely shaped to deal with their particular childhood traumas. Louise Bourgeois, Freud’s Daughter, the Jewish Museum’s exhibition catalogue—which is, in effect, a condensed version of Louise Bourgeois: The Return of the Repressed, Psychoanalytic Writings (2012), a two-volume book focusing on the artist’s writings—interweaves the story of her life with her writings and her art. These volumes suggest that much of Bourgeois’s work emerged directly from her rage at her father. Meanwhile, the catalogue Kusama: Cosmic Nature, though it pretty well skirts the topic of childhood trauma, can be read (in combination with Kusama’s wrenching 2003 autobiography, Infinity Net, and the 2020 graphic novel Kusama) as a tale of how Kusama’s sexual fears came to be transmuted into an art that’s all about losing oneself in nature, loving flowers (and their stamens), and being one with the cosmos.

Let’s look again at the two works mentioned above. When Kusama first showed Narcissus Garden at the 1966 Venice Biennale, she was just coming into her own in New York. At that point, her “Infinity Net” canvases—repetitive mesmerizing loops of paint with no focal point, which she pursued with an obsessive fervor—were becoming well known. (The critic and minimalist sculptor Donald Judd praised them in a review.) By this time, Kusama had also started making soft sculptures—rowboats, suitcases, and furniture covered with soft cloth phalluses. (Kusama claims in Infinity Net that Claes Oldenburg got the idea of soft sculpture from her, and that his wife apologized—“Yayoi, forgive us!”) What’s more, she was using some of her soft sculptures in her performance pieces. For Infinity Mirror Room—Phalli’s Field, 1965, she lolled about a mirrored room of soft red-and-white polka-dotted phalluses.

Narcissus Garden, Kusama’s first outdoor installation, seems to have grown directly from Phalli’s Field. That is, Kusama transfigured her carpet of soft phalluses into a garden of mirrored balls. At the Biennale, she used a green lawn as the platform for hundreds of balls, which reflected the sky and the visitors who bent down to see them. Nearby she planted a sign: “Your Narcissism for Sale.” Wearing a gold kimono, Kusama would lie down on the grass with the balls (just as she had lain among the polka-dotted phalluses) or stand among them. She sold the balls for twelve-hundred lire (two dollars) apiece until the authorities at the Biennale told her to stop selling her art like “hot dogs or ice cream cones.”

Today, Narcissus Garden, stripped of its sexual roots and its transactional aspect (the signs now say “Don’t Touch”), is inviting, kid-friendly, relaxing. As the exhibition catalogue notes, this “work that premiered as a pointed critique of the commodification of the art world” has now become “an immersive meditation on the ever-changing world” and a chance to “forget yourself.” But to me, those joyful bobbing balls will always evoke Kusama’s phallic productions.

The backstory of Bourgeois’s brooding Ventouse could not be more different. Bourgeois created Ventouse when she was nearly eighty, had some thirty years of on-and-off Freudian psychoanalysis under her belt, and had read every analyst from Wilhelm Reich to Jacques Lacan. (She was especially partial to the first generation of female analysts, Karen Horney, Helene Deutsch, Marie Bonaparte, Anna Freud, and Melanie Klein, whom she called “my companions in misery + dream.”) By the time she made Ventouse, her psychoanalytic thoughts had thoroughly seeped into her work, and she was well known for her phallic sculptures. The white marble portrait of her husband, whom she viewed as a maternal presence, was, for instance, a tiny head engulfed in dicks.

Ventouse was a departure for Bourgeois. An homage to her dead mother, Joséphine, it had no obvious Freudian message. (Maman, her thirty-foot-tall steel and bronze spider, came nine years later.) But if you consider the childhood memory that sparked it, the daddy overtones can’t be missed. Throughout Louise’s childhood, her mother was sick, and Louise, as a teenager, served (at her father’s behest) as a nursemaid to her, traveling with her to the South of France, caring for her, and applying to her back the glass cups, ventouses, that were supposed to relieve pain. All the while, Louise’s father was having an affair with Bourgeois’s English tutor, Sadie, just six years older than Louise. Ventouse, while explicitly about Bourgeois’s suffering mother, certainly refers to her cheating father, too.

Come to think of it, those lighted bulbs, those ventouses bubbling out of the chipped sarcophagus, strongly recall the red-hot phalluses of Bourgeois’s most angry and psychoanalytically charged work, The Destruction of the Father, 1974, which is also in the Jewish Museum’s exhibition. Bourgeois once explained that this violent supper scene—which included phallus-shaped stools around a table loaded with chicken bones that glowed under red-hot phallus-shaped lanterns—was “an exorcism.” It is an explicit retelling of Freud’s fantastical totem meal, in which a father is devoured by his angry offspring, whereby they absorb his power. As Bourgeois herself described the grisly Oedipal feast, “The children . . . put him on the table. And he became the food. They took him apart, dismembered him. Ate him up.”

Just as Kusama’s pool of floating balls can be seen as the successor of Phalli’s Field, so Bourgeois’s Ventouse, her heavy tribute to her mother, can be seen as the other half of The Destruction of the Father.

You may well wonder what set these two artists on their respective phallic obsessions. For Bourgeois, it wasn’t merely her father’s affair with her tutor. It was something more basic. I think Freud would call it “penis envy.”

When Bourgeois was four or five, she was taken by her mother to visit her father, a soldier wounded in World War I. Her mother was insanely jealous when she found her dashing husband being doted on by pretty nurses. On that visit, young Louise was locked in a closet while her parents had sex. Oddly, what Bourgeois resented most about this primal scene was being left out. She blamed her maman for keeping her “in the dark.” Abandonment and sex became a linked obsession and a theme of her work. As Bourgeois herself noted, as if she’d been cheated out of becoming her father’s lover: “At Oedipus time, I never had a chance.” Her redemption (or revenge) would be getting a phallus of her own. Freud’s Daughter quotes Bourgeois: “When my father left me / 1915 I wanted a penis to / replace him.”

To make matters worse, Bourgeois’s father, Louis, often chided Louise for her lack of a penis. From the film Louise Bourgeois: The Spider, the Mistress and the Tangerine (2008), we learn that he, on more than one occasion at the table (yes, another supper scene!), “cut an orange peel in the shape of a woman with the inner stem positioned where her genitals would have been. He then held up the figure to the entire family and said, ‘Well, I am sorry that my daughter does not exhibit such beauty because my little figure is very rich and obviously my daughter doesn’t have very much there.’” Bourgeois was mortified.

Kusama’s trauma over the phallus was nothing like that. Like Bourgeois’s father, Kusama’s was a sex hound. As Kusama writes in Infinity Net, he used to go to houses of prostitution and even seduced “the housemaids, one after another.” Kusama’s mother, furious with him, “would vent all her rage” on Yayoi, and then use her as a spy: she “would order me to follow him and report back.” When Kusama was very young she “happened to witness the sex act” and was horrified. “All the inner factors that cause me to perceive sexual intercourse as violence find form in the male sex organ.” That violence made peace and obliteration her key themes. She wanted to disappear. “My fear,” she writes, “was of the hide-in-the-closet-trembling variety.”

In other words, while Bourgeois wanted to be let out of the closet, Kusama wanted to hide in it, to disappear.

Kusama notes in Infinity Net that people generally assume that she’s crazy about sex and phalluses “because I make so many such objects.” But “it’s quite the opposite—I make the objects because they horrify me,” she has said. “I am terrified by just the thought of something long and ugly like a phallus entering me, and that is why I make so many of them. . . . I make them and make them and keep on making them until I bury myself in the process. I call this obliteration.” Kusama’s phalluses lose their power by being soft, numerous, and ridiculous. “I make a pile of soft sculpture penises and lie down among them. That turns the frightening thing into something funny, something amusing.”

By contrast, Bourgeois’s phalluses have the feel of big-game trophies. Many of them look as if they’ve been sawed off a man’s body. They are often strung up or imprisoned. They are the objects, or part objects, left after a castration. They have a violent and violated feel. In 1982, Robert Mapplethorpe photographed Bourgeois grinning as she carried under her arm a large plaster and latex penis, titled Fillette, 1968, which means “little girl.” It looks like Bourgeois has lopped off a giant’s penis. She finally got what she wanted all along.

Whereas Kusama’s method for overcoming her fear of phalluses (and macaroni too, apparently) amounted to a kind of exposure therapy, which she called “Psychosomatic Art,” Bourgeois dealt with her violent case of penis envy and Oedipal rage with what you might call acquisition therapy, by making some phalli for herself, just to get even.

“By now,” Kusama says, “the number of penises I have made easily reaches into the hundreds of thousands.” As for Bourgeois, according to The Return of the Repressed, she appropriated “the annihilating power” that she attributed to the phallus and refigured it “into her own artistic language.” Or, as the artist herself bluntly put it: “I manipulate them, they do not / manipulate me.”

Sarah Boxer is the author of In the Floyd Archives: A Psycho-Bestiary (Pantheon, 2001), a comic loosely based on Freud’s case histories, and its sequel, Mother May I?: A Post-Floydian Folly (IPbooks, 2019). Her work has appeared in the New York Review of Books, The Atlantic, and Artforum. (See Contributors.)