VLADIMIR SOROKIN is genius, pure and simple. Or Daedalian.

Slowly, slowly Sorokin has been introduced to us. At first he was suspected to be too “esoteric” for American tastes. Jamey Gambrell, who knew him via the literary and artistic underground of ’80s Moscow, was his first English translator. It was not until 2007 that a novel, Ice, centerpiece of a trilogy, appeared in the United States. In an interview with the Paris Review, Gambrell recalled that her early efforts troubled her because they made the work sound so odd. “It’s like, This is going to sound so weird. But then I stopped . . . and reread the whole thing in Russian and realized, Well, yeah, it’s extremely strange in Russian. And so there’s nothing else to do with it. You have to go with that weirdness.”

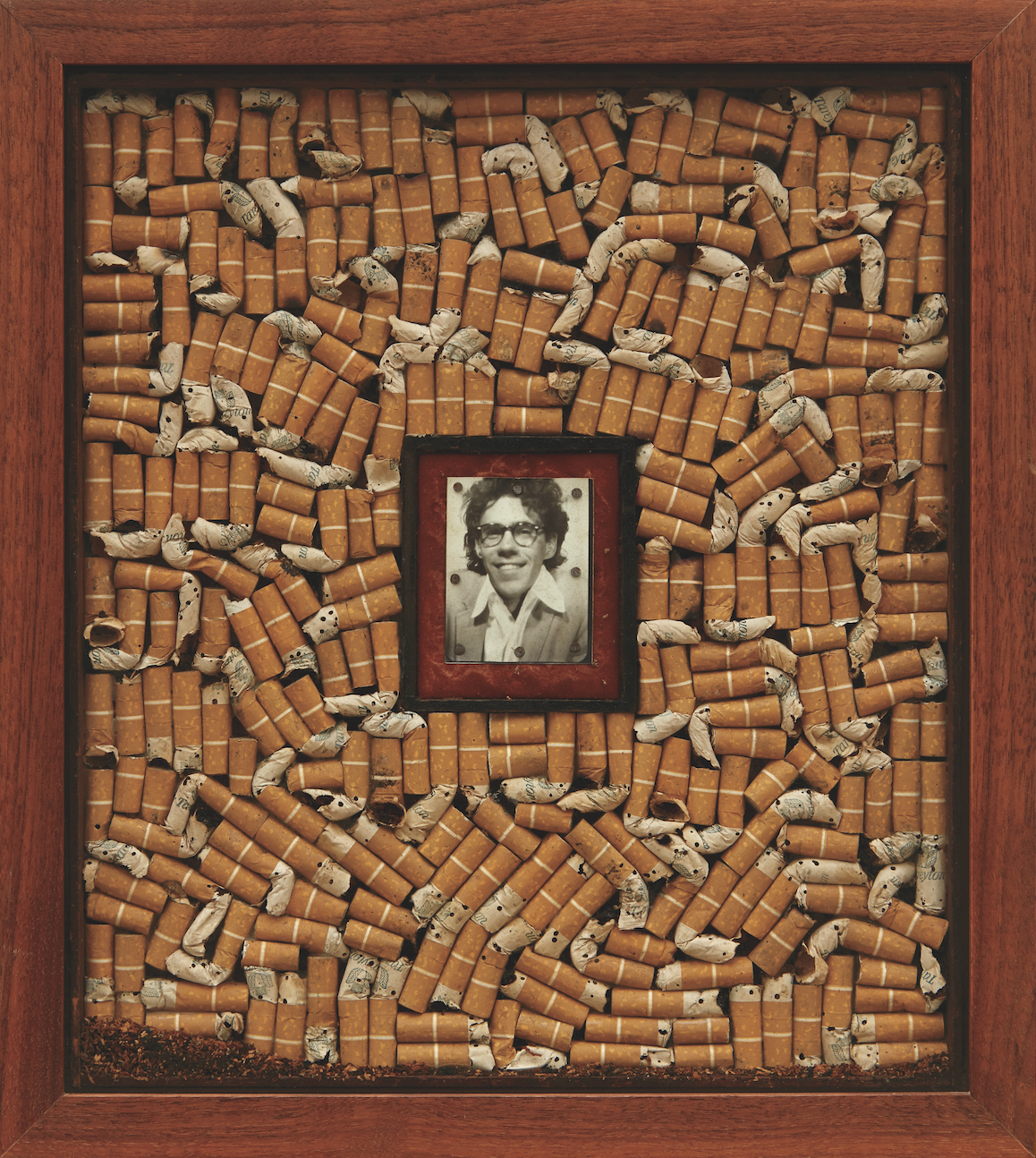

She also translated Day of the Oprichnik and The Blizzard before her death in 2020 at the age of sixty-five.

Gambrell was calm. She found balance, a path. She was on a long date with a wild man but could be trusted to bring us all home by midnight. Max Lawton, Sorokin’s new indefatigable translator, is willing to hang out much later, eager to push further toward an ever-receding dawn.

Two years ago, Dalkey Archive Press and New York Review Books respectively published Their Four Hearts (published in Russia in 1992) and Telluria (2013). Telluria is set in a medieval futuristic post-humanist landscape; with fifty chapters told from fifty points of view, it is linguistically and conceptually impressive, in vivid counterpoint to the gleefully abhorrent Their Four Hearts, of which Lawton wryly says: “It’s a light read. It’s hilarious.”

Now, New York Review Books is publishing a selection of Sorokin’s stories, Red Pyramid, and his infamous 1999 novel Blue Lard. In the latter, the sex scene featuring Stalin and Khrushchev only goes on for a few pages:

“Oh . . . how often I think of you . . .” Stalin murmured. “How much space you’ve come to take up in my boundless life . . . ”

“Masculinum . . . ” the count’s lips touched Stalin’s burgundy glans.

Stalin cried out and grabbed Khrushchev’s head with his hands. The count’s lips teased the leader’s glans—tenderly at first, then more and more carnivorously.

“A spiral . . . a spiral . . . ” Stalin moaned, digging his fingers into the count’s long silver hair.

Khrushchev’s strong tongue began to move in a spiral around Stalin’s glans.

“You know my dear . . . no . . . sacré . . . I . . . but no . . . the tip! the tip! the tip!” Stalin thrashed around on the down pillows.

The entire book is a vigorous scatological and satirical romp. A Russian-German meeting proceeds like so:

“There were also a lot of problems with the Holocaust,” Stalin pronounced. . . .

“Was there even a Holocaust?” Göring asked.

“Well, six million people died . . . ” von Ribbentrop remarked.

“That’s the Americans’ number,” Hitler said. . . . “Six million isn’t even that many. We lost forty-two million during the war.”

“Forty-five million, Mr. Reichskanzler,” Khrushchev interjected.

“I’m sticking with the German data,” Hitler noted drily.

There was a tense pause.

In an “Extroduction” Lawton says that Blue Lard isn’t to be read as much as borne witness to, its “quiddity” being “its own reward.” It will not tolerate the formal niceties of an introduction. The reader has to enter this . . . this substance unaccompanied. The thirteen stories in Red Pyramid more graciously accept discussion and are illuminated by Will Self’s fine intro, which comes close to articulating their glittering incomprehensibility by pointing out the mix of zaum, futurism, mysticism, masochism, and panpsychism that fuel their disturbances. Self also pinpoints nicely the moment of “helium lift,” a Sorokin specialty, when the story becomes something much other than the reader could possibly have imagined.

The first story in the collection, “Passing Through” (1981), concerns shit, also presented as “something brown” appearing “between . . . cachectic cheeks,” a “brown sausage”—produced on an underling’s tidy desk by a squatting party official.

That’s pretty much it. Though the shit deposit comes as some surprise actually. Sorokin had mastered the helium lift even at the age of twenty-six.

Shit has a role in the 2000 story “Natsya,” in which it contains the undigestible black pearl that reflects everything in the world as black, and in “Violet Swans” (2018), a beauty of a story, in which an excommunicated monk uses excrement as a binding agent to seal himself into an opening on a cliff’s rock face.

This hermit, who had performed worldly miracles in the past, is approached by members of the Russian military, who have discovered that the uranium tips in their nuclear warhead arsenal have turned to sugar . . . refined sugar. This, of course, if left uncorrected, would be the end of Mother Russia, Eternal Russia, Celestial Russia. A young soldier, Sasha, is chosen to ascend to the cave via an air-conditioned cube and convince the ascetic to change the sugar into thermonuclear triggers, much as he had once inadvertently caused holy bread—the prosphora in Orthodox liturgy—into stone. The scene is antic, the quest unfulfilled. And then Sorokin achieves helium lift, not just once but twice. The story ends with a flock of brilliantly plumaged birds awakening from a night’s slumber on the Ionian Sea to assemble in flight and head north toward Ithaca. Homer’s Ithaca, home in the most classical sense. Or Cavafy’s, journey’s end, in the poet’s words:

Ithaka gave you the marvelous journey.

Without her you wouldn’t have set out.

She has nothing left to give to you now.

Perhaps. A strange ending, Sorokin’s, as the birds in “a smooth violet wedge rose up in the matinal sky.” It brings to mind Kafka’s old saw: “There is an infinite hope; only not for us.” Sorokin’s birds are swans, of an improbable end-times violet, but they also recall Putin’s white Siberian cranes. In 2012, Putin, in a motorized hang glider, attempted to encourage a flock of young cranes, their kind critically endangered, to begin a six-thousand-kilometer migration to China and Iran. They would still be picked off by hunters representing many lands, but it was a nice gesture. He was widely ridiculed for this—Putin, leader of Russians and a few heretofore captive cranes. What a goofy guy, simple of mind and heart, a poseur. But now there is the Ukraine assault and the death of Navalny and reports of a new Russian satellite weapon, quite possibly nuclear, which is “troubling” and even annoying as we, America, would certainly want to be the first in developing and deploying such a treasure into space.

In “Violet Swans,” the disbarred monk, referred to by his beseecher as Father Pancras, does not address the reverse-transfiguration issue. When Sasha asks him in all earnestness, “What’re we to do?” he replies out of the cave’s darkness:

“Sleep!”

“What do you mean . . . sleep?”

“Sleep deeply!”

“Why?”

“So that you have more dreams.”

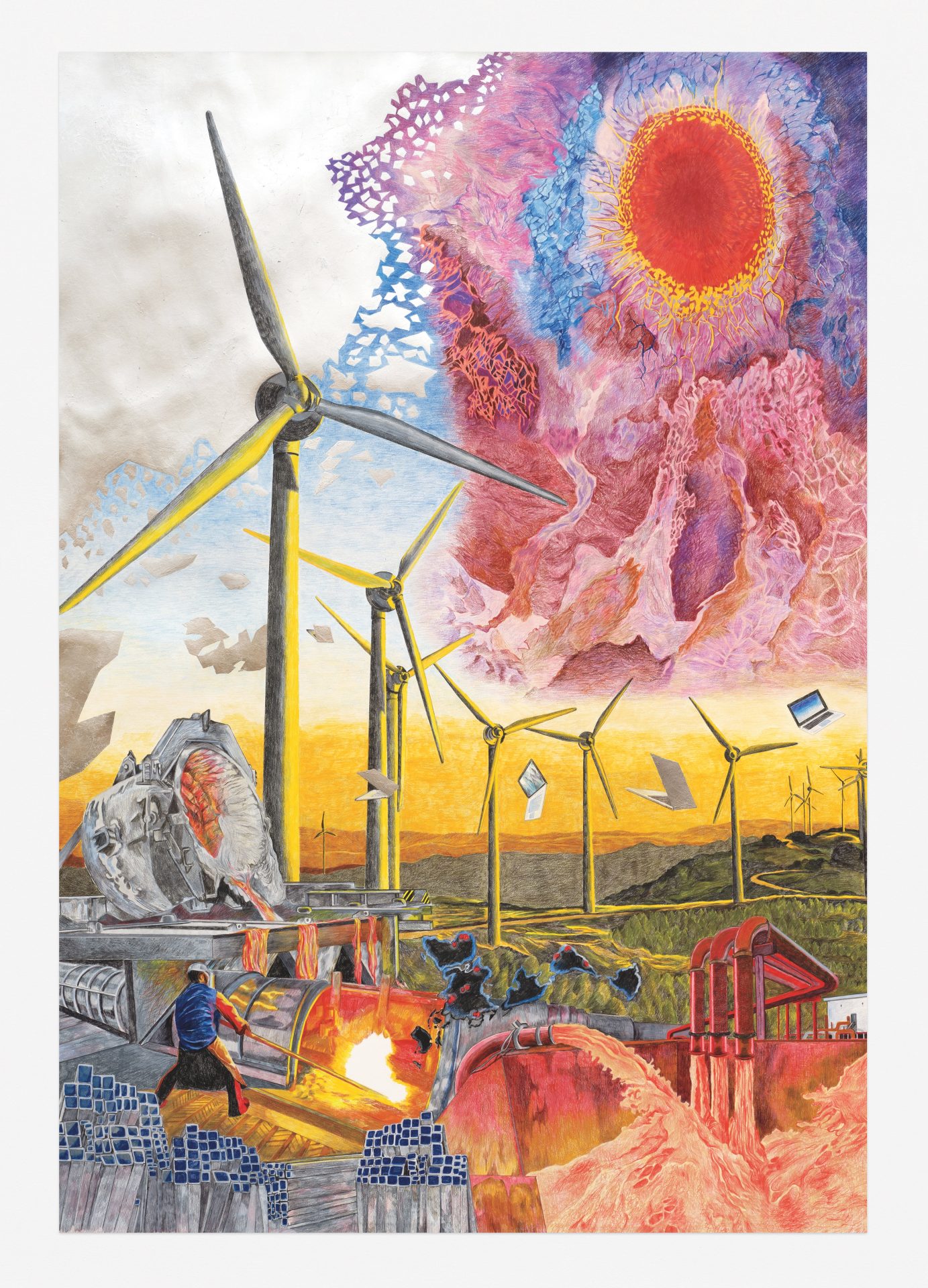

An extended purifying fast with Morpheus might not be a bad idea. Stumbling through this life in what we consider alert waking has brought nothing but imbalance and woe. Our fantasies have become more real, the real ever more incoherent, more foul. Could the world heal if we stopped engaging with it for a while? The Amazon, the steppes and seas, the pounded, bloodied, dis-lifed earth of Gaza? Could current conditions of consumption, war, and extermination be negated? Unlikely, for this is the Anthropocene, and the Anthropocene disallows such moony thinking, and so it will be until the Anthropocene is itself disallowed. Anyway, it would take too much time, an inhuman amount of time, a God’s own amount of time, even beyond the kind of timeless time Sorokin plays with in his startlingly realized anti-utopian fictions. Sorokin the man might find change—correction—desirable, but Sorokin the artist finds humankind’s self-inflicted dilemma irreversible.

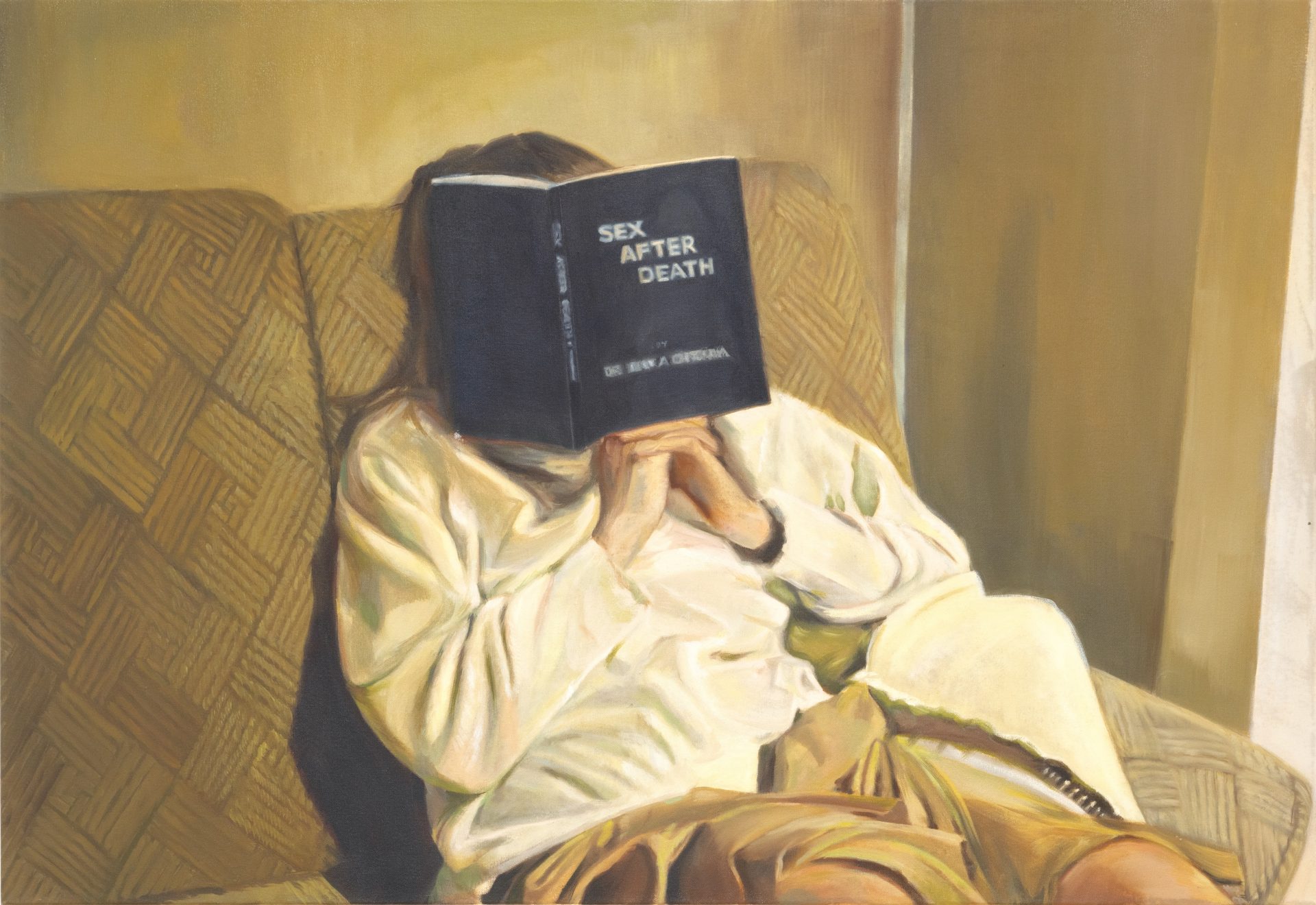

Sorokin has professed his admiration for literature. He finds beauty in the literary process. He likes the universality of it, the potential to inform, to have an effect upon people. Yet . . . it’s just lines on paper, too . . . it could be prank or goad, even code. Certain parties wish to view his work as primarily political and therefore useful, but that would be to simplify it, seal it, doom it to future irrelevance. Like Russia herself, which he mocks, mimics, and tears apart like a wolverine, his work is cruel, unpredictable, destabilizing, and extreme. It provides no comfort zones. Everything is paradox, wit, reversal, fearsome revelation, sometimes ecstatic, sometimes banal. It depends. The naughty ditties of childhood hold as much meaning as the prattle of elders discussing Nietzsche. The depths in a blind horse’s eye reveal the fearsome disorder of the future. A shining pickax of revenge bears the inscription Procul Dubio. Without a doubt.

That Sorokin can fashion the excessive energies of his novels’ recklessly assured plotting into the more confining structure of the short story is wondrous. He does this by dynamiting the form, shattering its veneer of melancholy modest disclosure (or its more recent giddy narcissism).

In “Horse Soup,” a wealthy man pays a young woman to consume carefully prepared dishes of nothing. Watching provides him with the most delicious orgasms, for watching another eat nothing in a kick-fueled society is the biggest kick of all.

A Russian spends his summer vacation (twenty-eight days) at Dachau, a sadistic Sadean holiday that culminates in glossolalic babble. A mother and daughter visit a grave and chant obscene obsequies.

Thoughts to chew on are literally the remains of a TV host who, leading a discussion on “What is Russia?” loses control over his drug-addled guests, is flayed, and ends up as an ingredient—tasting vaguely like tripe—in a poor couple’s supper.

In the unforgettable “Tiny Tim,” salvation from life for a grievously injured woman comes in the giganticized triumphal form of a beloved childhood pet. And in the title story, the pyramidical shape—long the symbol of sacred geometries encoded in spiritual consciousness—has been transformed into a raw symbol of roaring, engulfing death, of common stupid annihilation.

The collection ends with “Hiroshima.” A naked woman suckles newborn pups in a ruined landscape. “A bewitching sense of peace emanated from her. . . . She didn’t belong to the world, upon the ashes of which she walked.” This is the literature of entropy, the literature of wisdom. Procol Dubio. Sorokin has restored the risk to reading.

Joy Williams’s most recent novel is Harrow (Knopf, 2022).