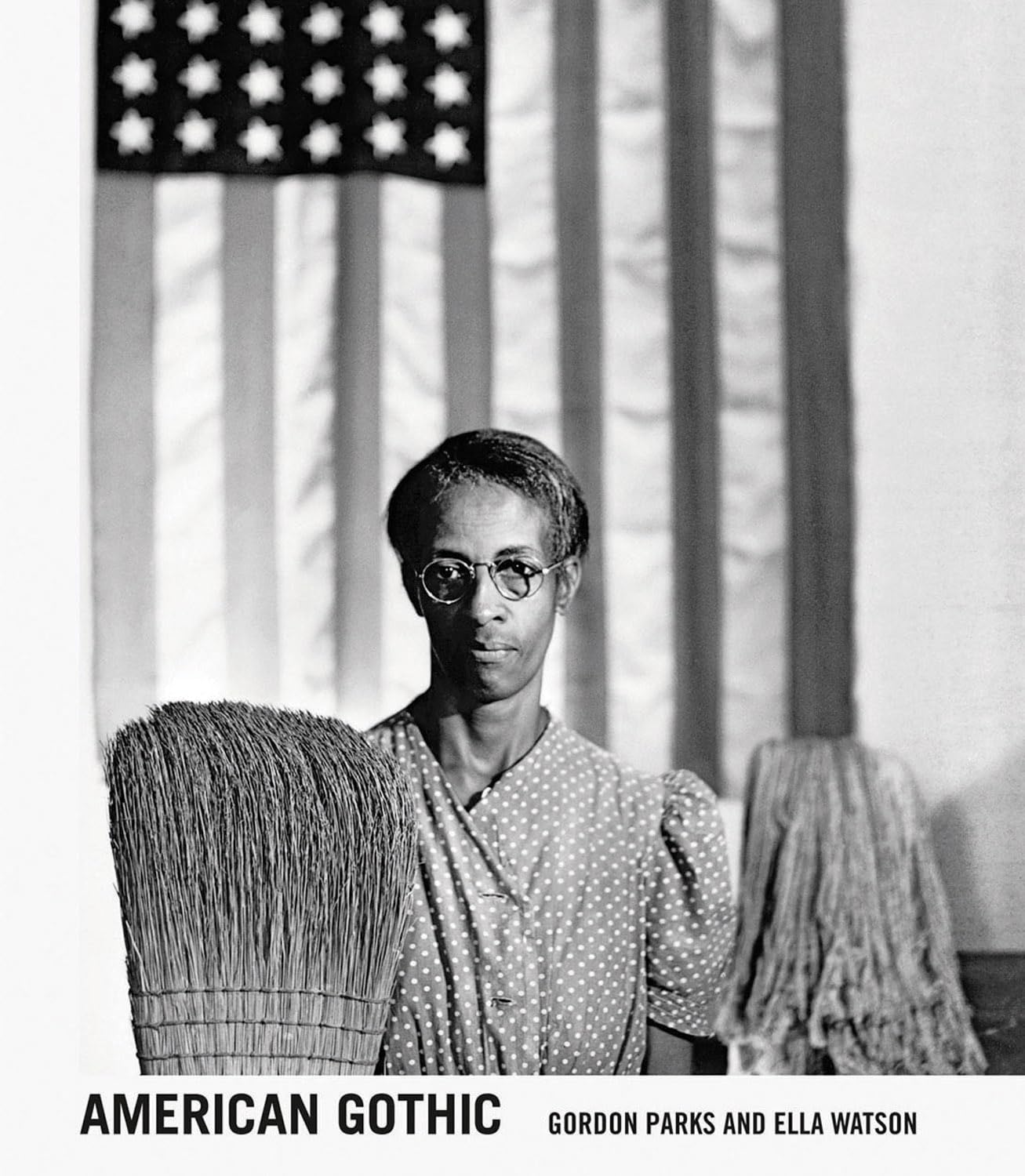

IN 1942, ELLA WATSON WAS A GOVERNMENT CLEANING WOMAN. Gordon Parks was a photographer for the Farm Security Administration (FSA). That summer, they met and collaborated on a photo essay that produced one of the twentieth century’s most striking images, Washington D.C. Government Charwoman (later renamed American Gothic). It was a breakthrough for Parks, who went on to become an influential writer, filmmaker, and photographer, as comfortable in Vogue as in Life and with at least one genre-defining Hollywood blockbuster, 1971’s Shaft,to his name. In a 2006 obituary, Greg Tate summarized Parks in seven felicitous words: “dapper, debonair, perpetually down for the cause.”

The cause: Parks said his camera was a “weapon against poverty and racism.” He meant that literally (taking pictures was how he got out of Minnesota) and figuratively, as works like The Restraints: Open and Hidden, a 1956 Life photo series about Jim Crow Alabama, became an armament against injustice. When he and Watson created their corollary to Grant Wood’s sourly folksy farm couple, Parks was still figuring out how to wield that weapon. As American Gothic: Gordon Parks and Ella Watson shows, Watson played an important role in that education. The book presents more than fifty images from the series alongside archival documents and six illuminating essays. We see Watson at work, at home, in church, and around her neighborhood. She was a stalwart in her community and an important influence on how Parks came to depict Black life in the American capital.

It’s relatively easy to show poverty and racism, but root causes usually remain out of frame. In the case of the American Gothic photo, it helps to know the backstory, which this new volume helpfully describes: Watson and a white woman began working at a government building at the same time. Watson was passed over for a desk job; the white woman got it; Watson cleaned the white women’s office from then on. So Watson and Parks staged a series of photographs in that flag-bedecked office. The book presents alternate snaps from that session, but they feel tentative, as the photographer and subject search for their angle. Then Watson looks at us straight on, her face resigned but with a hint of conspiratorial joy; she knows the room is rightfully hers. Your average FSA photographer might frame Watson from a lower angle, like a propaganda poster. But Parks didn’t need compositional cheats for this steadfast shot, which carries an acerbically elegant social critique. When Parks renamed the photo American Gothic, it became a double exposure; there’s a ghost image of America’s best-known painting of whiteness. Parks conjured root causes, even as he and Watson created a highly specific and very personal portrait.