ONE OF MY CLOSEST friends in high school was what we called hapa in typical Los Angeles casually racist slang. We had semi-pejorative epithets for every ethnic group and deployed them affectionately and indiscriminately across demographics, our scrappy anthropology. In my friend’s case, she was half-Japanese and half-Yugoslav. Her Yugoslav father had a storied journey to the United States that dominated their family’s suppertime banter in the presence of company, but one day I remember being at their house for dinner and gleaning from a private family patois I’d learned to decipher that her grandmother on her mother’s side had been in an internment camp. I was a junior in high school, seventeen years old, and multiple AP History courses into my indoctrination in the insurmountable achievements of Western Europe, but that dinner conversation was the first time I’d heard that during World War II the United States had rounded up Japanese Americans in a manic and arbitrary manhunt, and exiled them from their homes and livelihoods, into prison camps, using the contrived threats of espionage and sabotage to justify sudden, forced, and unwarranted incarceration.

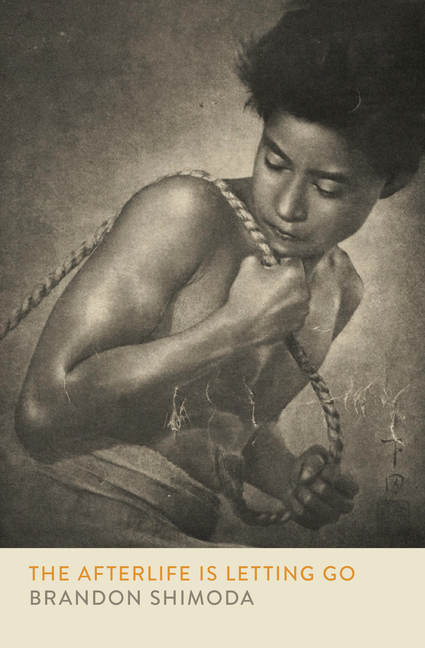

This modern enslavement disguised as a method of guarding the safety of US citizens was trained to silence itself, to help in the establishing of an etiquette of oppression so that, as Brandon Shimoda conceives in The Afterlife Is Letting Go, the state couldregenerate that silence as some semblance of tradition, rite of passage, or the wages of assimilation into the better-natured motifs of the fraudulently determined American Dream. What catechism of euphemisms and lies were we passing off as our cultural inheritance? By the time murmurs of “internment,” whispered and layered with internalized shame and near humiliation, had reached me, I’d already encountered outrage 101 slogans like “history is the autobiography of the victor.” Red-and-black Ché shirts from Urban Outfitters were popular on my high school campus, and the only boys I liked even a little wore them, read Sartre and Camus, wrote poems in the spirit of Saul Williams’s film Slam,and listened to Rage Against the Machine or esoteric jazz and hip-hop. Black music and culture, hip-hop culture, was inspiring a generation to question everything, especially the received protocols of social hierarchies, so that instead of conspiring with the silence of past generations we were trespassing on it clumsily, with inflated senses of entitlement and renewed vengeance for what our ancestors might have already reconciled as the price they paid to get us here. Where were we exactly, we wanted to know, if the unmasked empire could disorient us to the point of spiral and alienation, violating our faith in our nation and our families. What was the point of sparing us the details that nonetheless fueled our shared dysfunctions, made us subservient to false myths and projections of ourselves, and prey to the inevitable and fatuous “we’ve been lied to” disillusionment that set us back decades into a mire of debilitated bitterness where we argued internally about what the correct accounts of our history should be in tiny underfunded departments at universities, in songs, in private reading groups and public access radio shows that later moved to YouTube, etcetera, and mistook this lateral momentum for the height of radical community building.

My hapa friend’s answering machine played the section Lauryn Hill rapped in Haitian Creole on Wyclef Jean’s Carnival album,as it slides into ballading English, The path we should choose is the path we refuse, you can’t take the world when you die . . . Levez les mains, levez les mains. Wyclef chimes in French. Put your hands up, you’ll either be arrested or moved to praises and exegesis.Lauryn’s raspy downcast scripture as verse was a revolving awakening—every time you call your friend you pray the song answers.And I can’t tell if my recall of all of this is as if recalling our shared adolescent trauma, how it was awkwardly positioned as agency and joie de vivre, and how I knew one day I’d record and reconfigure its syntax, or if the intricacies of subtle, mounting epiphanies are always vying to resurface and be accounted for in movie scenes, novels, poems, essays. Our most minor days, it turns out, expanded our consciousness more than they forced adventure or formal study. The closer we listened to one another, the more coherent our hearts became with our intellectual understanding of the world, so that we could feel the truth before it revealed itself. Or we were one another’s detectives, spies into the details that should have been central to our worldview, details that had been suppressed by popular culture. All our ancestors had been brutalized, it’s just the blockbuster slave movies were about black Americans. Other groups suffered more politely, in shorter intervals, easier to clean up and reframe as alliances with their captors. Our abjection was sold back to us as high tragedy while that of other groups was tamed into complicity with the idea that it was just an unfortunate mishap, a bad mission that seemed necessary at the time—all is fair in war.

“INTENMENT” COMES from the Latin interrare—to bury or submerge in the earth, entomb. In a footnote on the first page of Shimoda’s almost true-crime account of the psycho-spiritual conditions that made it possible for the US government to enact Executive Order 9066, we learn that more than 125,000 Japanese Americans were buried alive this way, subject to what was sometimes referred to as “exclusion,” beginning in 1942 following the attack on Pearl Harbor, and ending in March 1946. One of the ten concentration camps was Topaz, in Delta, Utah, where one internedman was shot in the heart by guards, while leaning over to pick a flower. This incident provides the book’s opening image, unfurling like a noxious poison you don’t want to stop inhaling because it might give you a vision, divine insight, or just return you to yourself without the blindfold that renders all of your waking conversations preamble for the real and revelatory that you might otherwise never allow past the veil of small talk. Imagine not knowing that your own government encoded such a crime into law, that with the waging of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s blasphemous pen, entire families were disappeared, sent to a mass grave, surveilled, killed for affinities to gardens, targeted for being too good at agriculture and aggravating jealous white farmers (who, as Shimoda explains, prompted many to support the mass incarceration of Japanese citizens). Japanese Americans who weren’t interned were encouraged to evacuate the US voluntarily under the threat of their live burial, warned they might be next. Could American xenophobia and psychopathy induce the terraformation of an environment wherein the inventedother dissolved into mineral—stones on the landscape merging into unholy mountains, hidden places, secret rest stops on the path to acceptable modes of Americanism. Kill him before he learns how defiant it is to love beauty under fascism.

We’re taken from the martyr in Topaz to the reverberations of his murder through the community of inmates, then decades forward, to the delayed and opportunistic attempts of shamed white locals to create an official memorial in honor of the slain. The commemoration would be contingent upon the removal of the monument those interned at Topaz had instantiated, one that had appeared on the killing floor and never been tampered with or altered. The excuse for excavation was that it could be better preserved as artifact within a formal museum. Of course, the effort to turn the suffering of the othered into cultural capital for the art world succeeded, doubling the desecrations already incurred. The Afterlife . . . weaves between these precise re-castings of the sites of Japanese American subjection through mass incarceration, and the unruly memories of those who have been in proximity to the formerly imprisoned. Echoing the cataclysmic dullness of strip mall nomenclature, the Japanese American Historical Plaza in Portland, Oregon, emerges as refrain. The sterile well-intentioned site seeks to honor through the erasure that is bureaucratic homage: we give you this place, this is the only territory where your tribulation can be mentioned aloud and substantiated by mortar and remembrance. This is the region your memory is permitted to expand into, these are the terms: the past, the plaza; its expansion must be tidy, it must maintain strict borders, and decorum and stifle any protest outside of them. Shhh, here’s your plaza, your pitiful bribe, you’re lucky to have it.

We learn that in 1988, Ronald Reagan signed a Civil Liberties Act that allocated the interned and their families $20,000 in reparations, that many received checks in 1990 alongside apologies from George H. W. Bush. Some attended a public ceremony for the nation’s fragile, desperate optics, and the matter was put to political rest. Shimoda’s grandmother was among those who received one of the checks, which the family used toward expenses for her husband, Shimoda’s grandfather, who had Alzheimer’s by then and had all but forgotten his incarceration. Others used the funds for house repairs, education, first trips to Japan—or never touched them. The Afterlife Is Letting Go becomes an argument against reparations, a treatise on the impossibility of repair through monetization or monumentalization of state-endorsed crimes and atrocities. The dignity that may have been redeemed is snatched back by what amounts to ransom or hush money and half-hearted apologies, and this government policy is effective in that Japanese citizens, in being included in it as victims, are involuntarily complicit in minimizing their blighted years until they are the muted conversations over dinner, held fervently then glanced away from like a gaze averted from a bloody crime scene so you aren’t called in to testify. Your survival is the government’s alibi.

Because we have come of age during an era where unearthing stolen legacies is in vogue, encouraged as cultural currency and duty, our collateral in an ongoing siege that uses identity as a bartering tool, Shimoda successfully points out the fact that his digging could be read as a violation of the strict litany of euphemisms that allow assimilated Japanese Americans to project uncontested success or swift recovery, that ascent from outcast to model citizen that so many are inculcated in until it is the main virtue thenaturalized prioritize. But the digging, the entrenchment, the refusal to retreat, aggressive and double-minded as it is, produces unforeseen intimacy. The author’s family discovers a box of letters his grandfather wrote to his sister-in-law while incarcerated, an unlikely encounter with evidence of things not yet seen or even imagined. The stories within the letters, censored by screeners, are not harrowing or self-congratulatory. They describe daily routines, habits, unexpected delights, the moments when the joys of a free man with a free spirit superimpose themselves onto the chastised and bound.

Our ancestors’ untold tales visit us as haunts until we allow them through our own voices, is part of what Shimoda understands; he cannot help but speak, not for them, but to them, in front of us. Part of his task becomes figuring out how to have the conversation without making it spectacle or entertainment, where constantly signifying “this is serious” can quickly blur sincerity with didactic stodginess and negate its force. The writing is most effective when it lets the facts and the real-life characters choose plainness over fixation on or glamorization of calamity—no fanfare, no pretensions toward legendary heroism, no windfall from shady apologists. Instead, emphasis on the defiant bravery of making it through and leaving their record in blood, memory, and DNA, so that the writer invents their afterlife and stakes his own upon it. We learn that Shimoda didn’t attend his grandfather’s funeral, that the work of a book can be to elegize the unspoken while wresting it from the unspeakable, to be its tongues and testimony, and to return it to itself on its own terms. As heirs to trauma, we often dwell on vicarious injustice; we seek recognition retroactively, for kindred who have suffered and been denied justice. We feel worthy of a better destiny, where they felt lucky to stay alive in the center of death camps lined with flowers, barbed wire, and mercenary snipers. Shimoda’s grandfather, incarcerated in the desert awaiting his bride or muse, yearning for the bridge between life and purgatory to reveal itself as a fathomless scroll, elaborates on diversions: the texture of the cherries he expects in spring, the way the mountains leap off the horizon and fall up like failed suicides, geological patricide, the price he’s paid for his grandson’s inheritance, his new life, which is not governed by money but by the language that compels the dead to speak and enact resurrection so calmly, so detached from what it means to come back swinging. Sometimes I don’t wanna be a soldier, sometimes I just wanna be a man, another song from the year I learned about internment pleads, a year leaping into the present, the sweetness and innocence of our nihilism then, our Stockholm syndrome we mistook for righteous indignation, revoked by all the information and data we have now. The Afterlife manages to offer facts and previously redacted information without imploring us to have a tantrum over it, or take up arms, aware that a reliable witness heals the memory, cures it of grudges, forces it to remain as vast as the desire to touch a flower when the guns are pointed toward you, to trigger them so they know you’re alive when they pull the trigger. Better to leave here alive than leave here dead.

Harmony Holiday is the author Maafa (Fence, 2022; UK edition, 87Press, Spring 2025).