LITTLE WALTER’S “Blues with a Feeling” is a majestic song whose title is kind of redundant. Blues is a feeling, whether filtered through Hank Williams’s full-moon howling or channeled through Jimi Hendrix’s rumbustious guitar. The emotional impact arrives far in advance of any intellectual engagement. The same process applies to the music of progressive jazz legend Cecil Taylor, however complex, densely polychromatic, or elusive its relationship seems to rhythm—or, for that matter, blues. The connections to both are there if you listen closely without overthinking matters.

It can’t be emphasized enough: you don’t “think” your way through Taylor’s music. Total abandon is closer to the objective. What may at first seem overpowering, eccentric, or dissonant in his profoundly quirky approach to jazz piano can’t be broken down to basic elements because those elements propel and transmogrify his solos organically more than cerebrally. New worlds of sound, forcing themselves into existence on their own terms, are summoned from Taylor’s impromptu tempests of arpeggios and exploding chords.

Not everyone buys what Taylor, or his body of work, has been selling. At times, his stuff mostly confused listeners and musicians alike. “What the fuck was that?” was the backstage reaction from the British blues-rock band the Yardbirds after a Taylor-led combo played for an hour and ten minutes at a 1968 concert at San Francisco’s Fillmore West. At other times, the responses have been more dismissive. Probably the most conspicuous dissent in recent memory came during Ken Burns’s 2001 documentary mini-series Jazz, in which a five-minute swatch on Taylor, in the show’s tenth and last installment, acknowledges his impact but questions his significance. In that segment, saxophonist Branford Marsalis ridiculed any notion of Taylor’s audience as collaborators as “total self-indulgent bullshit.” Most likely, your stance on Taylor’s body of work depends on whether you see it as a series of impenetrable, sharply pronged fences or as spaces wide open enough for you to roam, dance, go about your business—or rewire your presumptions.

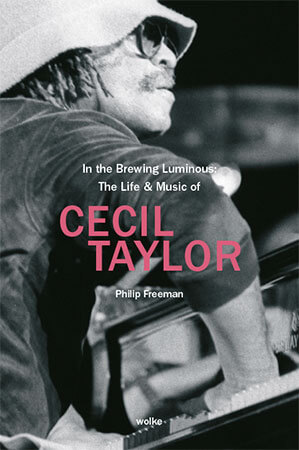

Philip Freeman’s In the Brewing Luminous offers the most persuasive and comprehensive brief for the music’s defense since Taylor’s death, at eighty-nine, in 2018. Freeman’s chronicle of Taylor’s crowded life and variegated work extends in length, scope, and even tone the illuminating biographical sketch included in 1966’s Four Lives in the Bebop Business, poet A. B. Spellman’s classic and still-essential composite portraits of Taylor and fellow mid-twentieth-century jazz insurgents Ornette Coleman, Herbie Nichols, and Jackie McLean. It’s possible, even necessary, to think of In the Brewing Luminous, whose title comes from a Taylor composition willed into being by one of his “units” at a 1980 New York club date, as a densely detailed chronicle of an artist assembling the rudiments of his style and being on his own highly subjective terms and, against formidable odds, adhering to and broadening his vision to the end. With a seasoned, cultivated ear, Freeman, whose previous work includes 2020’s Ugly Beauty: Jazz in the 21st Century, brings a clean, direct style to his conscientious survey of Taylor’s half-century-plus of recorded output, helping readers who may not be familiar with the music but are curious anyway. And those more familiar with Taylor’s work will both find communion with and derive fresh meaning from Freeman’s account, thanks to his measured use of analogy and metaphor that at no time feels piled-on or exaggerated for effect. Freeman’s specialties are jazz and metal, two genres as capable of the madly intricate as the heroically ecstatic. Ramrod composure of some degree seems necessary to diligently catalog however many means there are to Bring the Noise, as it were.

Here, for example, is how Freeman breaks down one of Taylor’s early-’80s solo recitals:

His fingers have the impact of sledgehammers. He repeats small phrases again and again, changing them slightly then returning them to their previous form, then coming up with a new idea and examining that from as many angles as he can think of. On and on it goes, tiny variations accruing until the whole thing is like a hand-woven carpet covering the entire floor of a vast room.

Taylor, born and bred in New York City and schooled at Boston’s New England Conservatory, absorbed an eclectic panoply of influences in both classical music (Schoenberg, Bartók, Webern, Stravinsky) and jazz (Bud Powell, Lennie Tristano, Erroll Garner, Dave Brubeck) to develop his own distinct, determinedly nontraditional sound. (“Everything I’ve lived, I am,” Taylor told his sometime producer Nat Hentoff in the liner notes of his 1959 album Looking Ahead. “I am not afraid of European influences. The point is to use them—as [Duke] Ellington did—as part of my life as an American Negro.”) In his early days as a professional musician in New York City, Taylor paid his dues playing with West Indian dance bands in Harlem for $5 and $30 a night while collecting scattered jazz gigs in different bars and working through a welter of odd jobs. In the aforementioned Ken Burns documentary, Hentoff tells a story, not found in Freeman’s book, about how Taylor got through a lean stretch, during which he delivered coffee and sandwiches during the day, by playing “imaginary concerts” at home “with a complete repertoire” of music. These, Taylor told Hentoff, not only kept up his morale, but allowed him to continue forging and advancing his ideas.

Taylor was becoming, in Spellman’s words, “a kind of Bartók in reverse,” a composer whose mercurial and almost furiously transgressive approach to what his partisans considered “spontaneous composition” had broadened horizons for jazz piano while arousing rancor, even hostility, among listeners and fellow musicians who saw him as an outlier deserving consignment to jazz’s margins. Even while Taylor struggled financially, his growing renown in the 1950s was putting him in the company of zeitgeist poets and painters of the era, including Frank O’Hara, Allen Ginsberg, Franz Kline, Larry Rivers, Diane di Prima, Bob Kaufman, and Amiri Baraka, then known as LeRoi Jones, with whom Taylor had a long and what Freeman characterizes as a “combustible” relationship. Among jazz musicians, Taylor’s acceptance was, to say the least, divided. Some notables of the bebop generation—for instance drummer Max Roach—were longtime friends and occasional collaborators. On the other hand, there was the Prince of Darkness himself, Miles Davis, who, upon encountering Taylor on a Manhattan street in 1957, stared at him before spitting on the ground. The slight was as lasting in Taylor’s memory as Davis’s contempt for Taylor’s music. “He’s bullshittin’,” Davis often said over the years of Taylor, even as Davis’s own music internalized some of the same free-form tactics developed by Taylor and other avant-garde players. For his part, Taylor fired back over time with characteristically gnomic whimsy, observing once that Davis “plays pretty good . . . for a millionaire.”

Ironically, Taylor shared with Davis the relentless impulse to grow, adapt, and reinvent himself. The modernist imperative of Making It New never left Taylor, and his loyal audiences, which swelled beyond America’s borders, were impelled almost to the end of his life to catch up.

In many ways, Taylor’s sustained raising of the musical ante began with the 1962 European tour with saxophonist Jimmy Lyons and drummer Sunny Murray, which yielded the remarkable Café Montmartre performances recorded and later released under the title Nefertiti, the Beautiful One Has Come. Freeman joins a consensus of historians, critics, and listeners in deeming these sessions “a major advance, not just in [Taylor’s] music, but in jazz as a whole.” His music was now firmly in the vanguard of what became known in jazz circles as “the new thing” or “free jazz,” and if those who remained loyal to the music’s mainstream still considered him an abnormality, they could no longer ignore or dismiss him.

By the early ’70s, Taylor was making what Freeman describes as “the most powerful music of his life.” This was about the time I first engaged Taylor’s music, and it is clear from Freeman’s vivid evocation of Silent Tongues, the 1975 album of his five-movement solo suite performed live the year before at the Montreux Jazz Festival, that he feels the same deep affinity for it as I do: “Taylor . . . establishes a theme and a structure built around small melodic cells that alternate between romantic gestures and low rumbles. There are passages that thunder, and others that land as softly as summer rain.” In jazz parlance, this pretty much “cuts” what I wrote about the album in my apprentice jazz critic days, when I compared the music to the sounds one’s ears pick up when one is swimming for one’s life. From the ’70s onward, Taylor ramped up the breadth, density, and intensity of his music, stretching the boundaries of his eccentric, propulsive dynamics in solo and ensemble performances by adding freewheeling choreography and discursive, inscrutable free verse in concerts throughout the world.

Freeman compiles and organizes as many elements and aspects of the Taylor corpus as can be woven into his crowded narrative. Still, In the Brewing Luminous keeps Cecil Taylor the person at a relative distance. Early on, Freeman acknowledges Taylor’s homosexuality and the tension it created with Taylor’s father. That part of Taylor’s life comes up intermittently in the book, notably in critic Stanley Crouch’s notorious early-’80s Village Voice article about gay Black artists who “outed” Taylor in a “sidelong mention” that “rankled” Taylor for years afterward. Of being labeled “gay,” Taylor said: “Do you think a three-letter word defines the complexity of my humanity. I avoid the trap of easy definition.” I wonder if someone thought to put that last sentence somewhere on Taylor’s tombstone.

In any event, it is only in the latter parts of the book that I mostly found the Cecil Taylor I have heard about from his acquaintances: the habitué of discos in Berlin, New York, and other cities; the homeowner in Brooklyn’s Fort Greene neighborhood whose house was, in a relative’s words, “always falling apart”; the witty raconteur hanging out all night in Lower Manhattan nightspots like the 55 Bar or the KGB Bar, telling stories about jazz musicians, writers, painters, and others he’d known. That’s the Cecil Taylor I wanted to read even more about.

It’s a somewhat bittersweet sensation to join Freeman in celebrating this grand legacy of improvised music as our attention spans are now constricted by TikTok and our nervous systems unsettled by prospects of artificial intelligence. Still, one could imagine, with all the boldness of a Cecil Taylor, that a future of increasing limits could create a vacuum in which the galvanic and volcanic combination of sounds invented by free-jazz avatars like Taylor could be reintroduced and widely embraced. If such maximalist giants as Beethoven, Brahms, Stravinsky, and Mahler could be venerated decades after their passing, so could a singular force of nature such as Taylor. You only need to hear him once to believe that anything, maybe everything, is possible.

Gene Seymour is a writer living in Philadelphia.