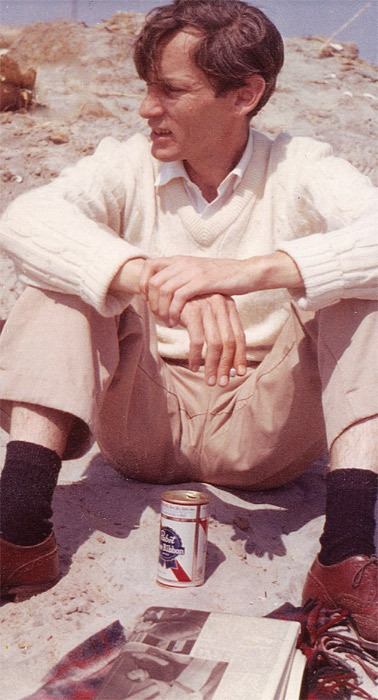

Drunk and Disorderly

Charles Jackson barely ever wrote a piece of fiction. The vast majority of his output—five novels or collections in the decade beginning 1944, and one final novel fourteen years later (“99 percent of this novel is lubricious trash,” read the Kirkus review)—was thinly disguised fact. His first, and by far his best-known, work was The Lost Weekend; it was essentially his homosexual alcoholic’s diary artfully made fiction. It made headlines for its depiction of alcoholism; the homosexual component got far less attention, likely because of the distorted Freudian fever gripping the nation, in which