IT IS FITTING THAT BRUCE ADAMS’S NEW BOOK, the sardonically titled You’re with Stupid: kranky, Chicago, and the Reinvention of Indie Music, begins at Jim’s Grill on the North Side: it was the first place I remember seeing a promotional poster for this new band, the Smashing Pumpkins, who were regular customers of Bill Choi’s Korean-inspired restaurant when they were first starting out.

- • Dec/Jan/Feb 2023

- • Dec/Jan/Feb 2023

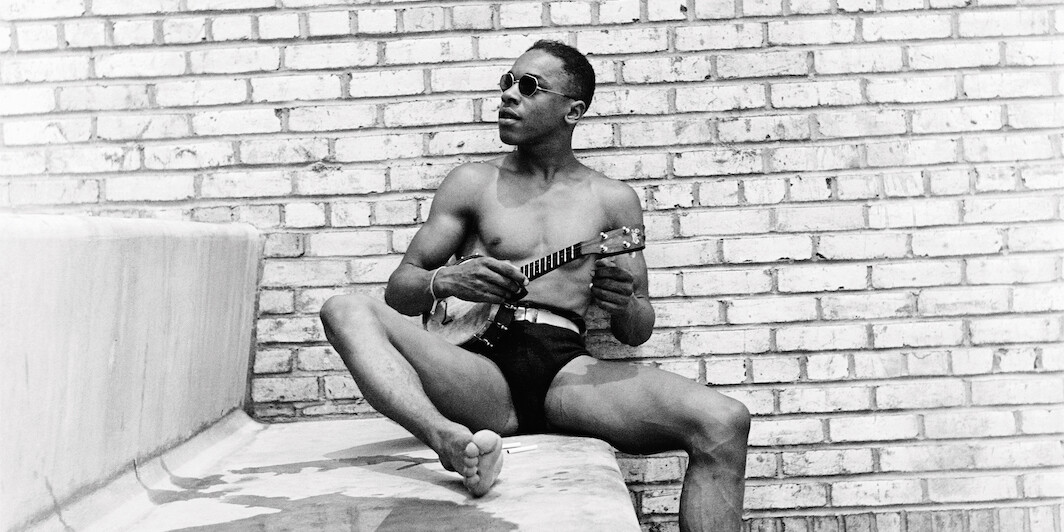

Pierre Fatumbi Verger, Colonial Park Pool, Harlem, New York, 1937. © Pierre Fatumbi Verger BORN IN 1902, Pierre Verger became a successful photojournalist in his native France, in 1934 cofounding an agency whose members included the likes of Robert Capa and Henri Cartier-Bresson. He lived mainly in Brazil from 1946 until his death fifty years later, […]

- • Dec/Jan/Feb 2023

AS A CHILD, I dreamed I would one day become a fashion designer. It’s one of those gigs, like astronaut or firefighter, that seems fun until you get too old to overlook the occupational hazards. For fashion, the dangers have long been hidden. In recent years, news coverage of “fast fashion,” a deceptively light term for cheaply manufactured clothing that pollutes landfills and oceans while exploiting and endangering workers, has proliferated—while solutions have not. The disconnect is understandable though hardly excusable: consumers look to material goods to change the way they feel, and fashioning a new sense of self doesn’t usually

- • Dec/Jan/Feb 2023

Frank Bowling, Doughlah G.E.P., 1968–71, acrylic on canvas, 90 × 71 7∕8″. © Frank Bowling. All rights reserved, DACS/Artimage, London & ARS, New York. Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston IN 1969 THE BRITISH-GUYANESE painter Frank Bowling curated a show at the art gallery of Stony Brook University that included, along with himself, five African […]

- • Dec/Jan/Feb 2023

Salman Toor, Crying Boy with Candle, 2021, oil on panel, 16 × 12″. Echoing the murky sheen of sidewalk puddles, Salman Toor’s paintings revel in the absinthe-green palette of inebriation and hallucination. His compositions whisper of the dark delights of unlit alleyways, of clandestine trysts in the garden, or the unexpected thwack of a cricket […]

- • Dec/Jan/Feb 2023

LAST WEEKEND I WENT to a party where people were wearing black lipstick, tropical shirts, chokers, and little drink umbrellas behind their ears. That was because the theme was “Hot Topic in the Tropics.” Many of the same people had recently been at another party where we danced on an Astroturf rooftop at a house rumored to be owned by the daughter of a famous dead novelist where there was a bathtub full of beers. Most of us had met at a succession of parties held in different cities over the course of more than a decade: birthday parties, magazine parties,

- • Dec/Jan/Feb 2023

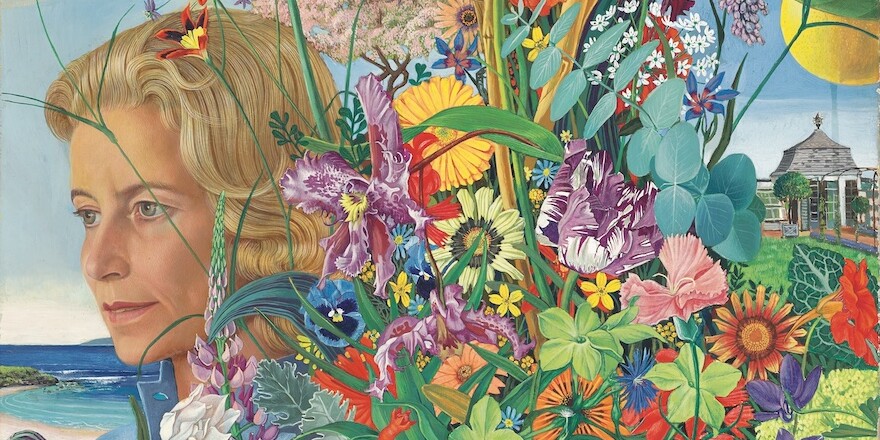

WHO WAS BUNNY MELLON? A photo caption in the opening pages of the new book I’ll Build a Stairway to Paradise: A Life of Bunny Mellon (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $40), by her erstwhile ghostwriter-cum-biographer Mac Griswold, describes her simply as “icon and woman.” More specifically, Mellon was a lifestyle pioneer, for whom the domestic space—the garden and home, with its antiques and art, but also its mood, energy, and ambience—was a Gesamtkunstwerk. She didn’t simply throw parties, she transported guests into ephemeral realms. As a mentor and bestie to First Lady Jackie Kennedy, she helped mold the aesthetic of

- • Dec/Jan/Feb 2023

JEREMIAH MOSS’s FERAL CITY concerns the summer of 2020, when after covid’s devastating first pass through New York City and the consequent exodus of everyone who could afford it, an invisible city rose up. The poor, the young, the nonwhite, the queer, the marginal were its constituents, and they made full use of public spaces […]

- • Dec/Jan/Feb 2023

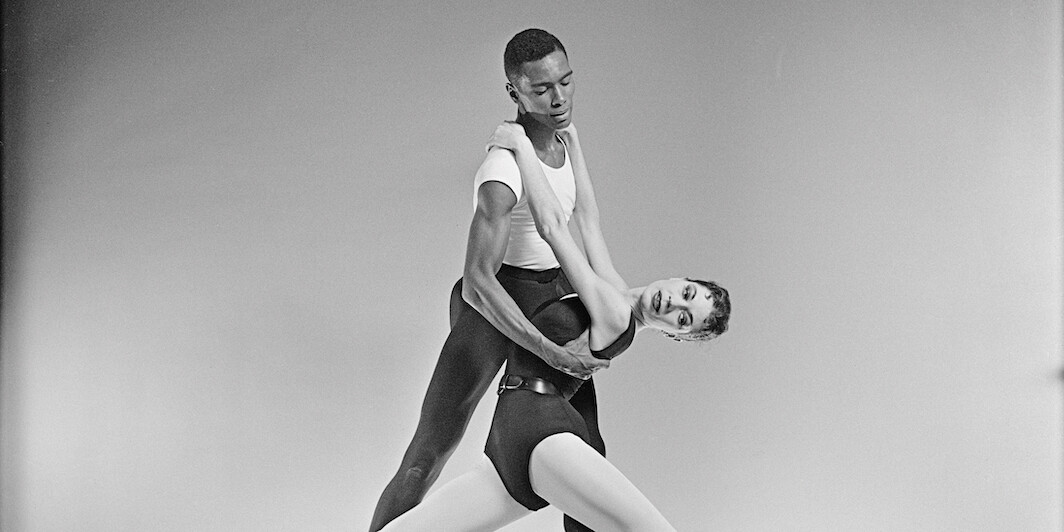

A QUICK GLANCE at the facts of George Balanchine’s life suggests that he was destined to be a great choreographer. Born in 1904, he studied at what was then the most important ballet academy in the world, the Imperial Theater School in St. Petersburg; in the ’20s, he made dances in Europe for what was then the most important company in the world, Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes; by midcentury, in the United States and with his own troupe, he would finish creating what is still probably the most important choreographic canon in the world, Balanchine’s ballets. But Jennifer Homans’s new biography shakes

- • November 29, 2022

Welcome to the Dec/Jan/Feb 2023 issue of Bookforum! In this edition, read: Harmony Holiday on Hilton Als’s conflicted love letter to Prince; Justin Taylor on whether Cormac McCarthy is “our most minor major novelist or is he our most major minor novelist”; Christine Smallwood on a new biography of Shirley Hazzard; Becca Rothfeld on Colette’s Chéri novels and the mantle of girlhood; George Saunders interviewed by Angelo Hernandez-Sias; Siobhan Phillips on choreographer George Balanchine and the fragile contingency of genius; Lisa Borst on Sam Lipsyte’s 1990s neopunk noir novel; Rebecca Ariel Porte on Ian Patterson’s new translation of Proust’s Finding Time Again; Michael

- • November 14, 2022

SHIRLEY HAZZARD WAS BORN in Sydney, Australia, in 1931. She was the second daughter of Reg and Kit, who met while working in the office of the engineering company that built the Sydney Harbour Bridge. Theirs was a marriage marked, as Brigitta Olubas puts it in Shirley Hazzard: A Writing Life, by an “almost lifelong incompatibility” made more difficult by Reg’s alcoholism and Kit’s bipolarity. Shirley was Kit’s favorite. When she was six or seven years old, Kit asked her to come to the kitchen so they could together put their heads into the gas oven. Shirley later said that the

- • November 8, 2022

A MONTH BEFORE Atlanta hosted the first hip-hop-focused spinoff of the BET Awards in 2006, an executive at the cable network joked the event would likely not benefit the local economy. He was probably right. Rap dollars already coursed through the Southern city like its ceaseless traffic, bankrolling recording studios, propping up nightclubs and music-publishing companies, and sustaining a vast corps of DJs, strippers, bodyguards, and lawyers. After the inaugural BET Hip Hop Awards aired and nearly half the honors went to Atlantans, local rapper T. I.—who won four awards that night, the largest individual takeaway—described the show’s location as the

- print • Sep/Oct/Nov 2022

IN HER BOOK Why I Am Not a Feminist: A Feminist Manifesto, published the winter after Hillary Clinton lost the presidential election, Jessa Crispin made it clear that she wanted nothing to do with neoliberal girl-boss feminism, which she argued was toothless, counterrevolutionary, and “ended up doing patriarchy’s work.” She did, though, want to be part of something. Crispin concluded by calling for a movement in which people would “stop thinking so small,” “remember that our world does not have to be this way,” and “see beyond the structures we’ve been given.” Her new book, My Three Dads: Patriarchy on the

- print • Sep/Oct/Nov 2022

WHEN I FINISHED MY FIRST READ of Which as You Know Means Violence, critic Philippa Snow’s debut “on self-injury as art and entertainment,” I returned to my own cultural hallmark of suffering, the 2006 film adaptation of The Da Vinci Code. Reading Snow’s analysis of artist Chris Burden’s 1974 crucifixion atop a Volkswagen Beetle alongside the comical stunts of Johnny Knoxville and his squad of Jackass pranksters, I thought frequently of Paul Bettany’s fanatical Silas, who torments himself to such extremes that he plays at the brink of absurdity. Silas spends most of his screen time scurrying around church cloisters in

- print • Sep/Oct/Nov 2022

AT THE END of a long Michaelmas term working in the Barbara Pym archives in the Bodleian (how about that for an opening gambit?), I, six months pregnant with my second child, took a train out past Charlbury, caught a tiny bus, and deposited myself, thankfully in Wellington boots, on the side of the road near Finstock. I walked across two very muddy, December fields and found myself loitering outside of Holy Trinity, a mild, rundown, Victorian church. The church itself is a bit of a mishmash of Gothic Revival and practicality, with its 1905 chancel poking out awkwardly through its

- print • Sep/Oct/Nov 2022

WHEN I BEGAN WRITING ABOUT DANCE in the early 2000s, the Martha Graham Dance Company was only just staggering out of a horrifying limbo. Graham had died in 1991 at the age of ninety-six, leaving her estate to Ron Protas, a man decades her junior who had become her close companion late in her tumultuous life. The controversial heir laid claim to the Graham repertory—a body of work foundational to modern dance, not to mention the Martha Graham Dance Company’s reason for being. Only in 2002, after a ruinous series of events had shuttered the entire organization, did the troupe win

- print • Sep/Oct/Nov 2022

AS A CHILD, SERGE DANEY KNEW his father only through the stories his mother told him. According to legend, Pierre Smolensky was a worldly, well-to-do gentleman involved in the business of cinema; throughout the interwar years, he dubbed films and perhaps even appeared in some under the stage name Pierre Sky. Only seventeen when Pierre took her under his wing, Daney’s mother claimed that he spoke all the languages in the world. For a while, the memory of Pierre was preserved in mythological amber, not unlike the images of Cary Grant and James Stewart, those beautiful American stars whom the fledgling cinephile

- print • Sep/Oct/Nov 2022

DO NOT MISTAKE Lynne Tillman’s Mothercare: On Obligation, Love, Death, and Ambivalence for a memoir. While it is unflinching, this book isn’t primarily about the vexed origins or aftereffects of the fraught mother-daughter relationship it describes (although all of that is in here). Rather, it is about performing the duty of keeping a person safe in an age when medicine often prolongs our lives long past our capacities. In this sense, Mothercare is more of an essay, or a dispatch: reportage from the trenches of care work. The “great difficulty” of writing, Elizabeth Hardwick once noted, “is making a point, making

- print • Sep/Oct/Nov 2022

Before Joan Didion died in 2021, she and her friend, fellow writer Hilton Als, discussed a possible “exhibition as portrait” that would put visual art in conversation with her writing. The resulting exhibition opened at the Hammer Museum (Los Angeles) this fall, and the catalogue, JOAN DIDION: WHAT SHE MEANS (DelMonico Books/Hammer Museum, $40), includes many of the pieces on display. Didion’s time in New York City, where she worked for Vogue in the 1950s and early ’60s, is represented by some iconic Arbus, Avedon, Hopper, and Warhol images, and by lesser-known works such as Helen Lundeberg’s Studio—Afternoon, 1958–59, an

- print • Sep/Oct/Nov 2022

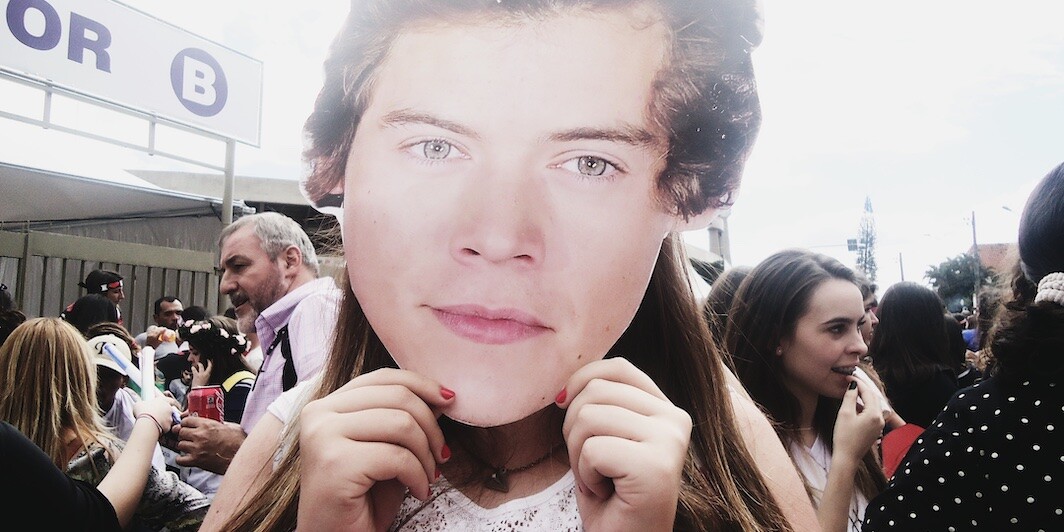

IN OCTOBER OF 2014, HARRY STYLES WENT FOR A HIKE in Los Angeles, and on the way back, made his driver pull over so he could puke by the side of the freeway. Paparazzi took photos, which circulated online and in tabloids. One fan visited the location, marked it with a sign reading “Harry Styles Threw-Up Here,” and posted a picture to Instagram. Five years later, Kaitlyn Tiffany, One Direction fan, staff writer at The Atlantic, and author of Everything I Need I Get from You: How Fangirls Created the Internet as We Know It (MCD/Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $18),