A YOUNG POLE WITH LUNG DISEASE arrives in the Silesian village of Görbersdorf in a mountain valley known for its good air and tuberculosis sanatorium. The year is 1913, and people are talking about the theft of the Mona Lisa from the Louvre and political tensions in the Balkans. He checks into a room in […]

- print • Fall 2024

- print • Fall 2024

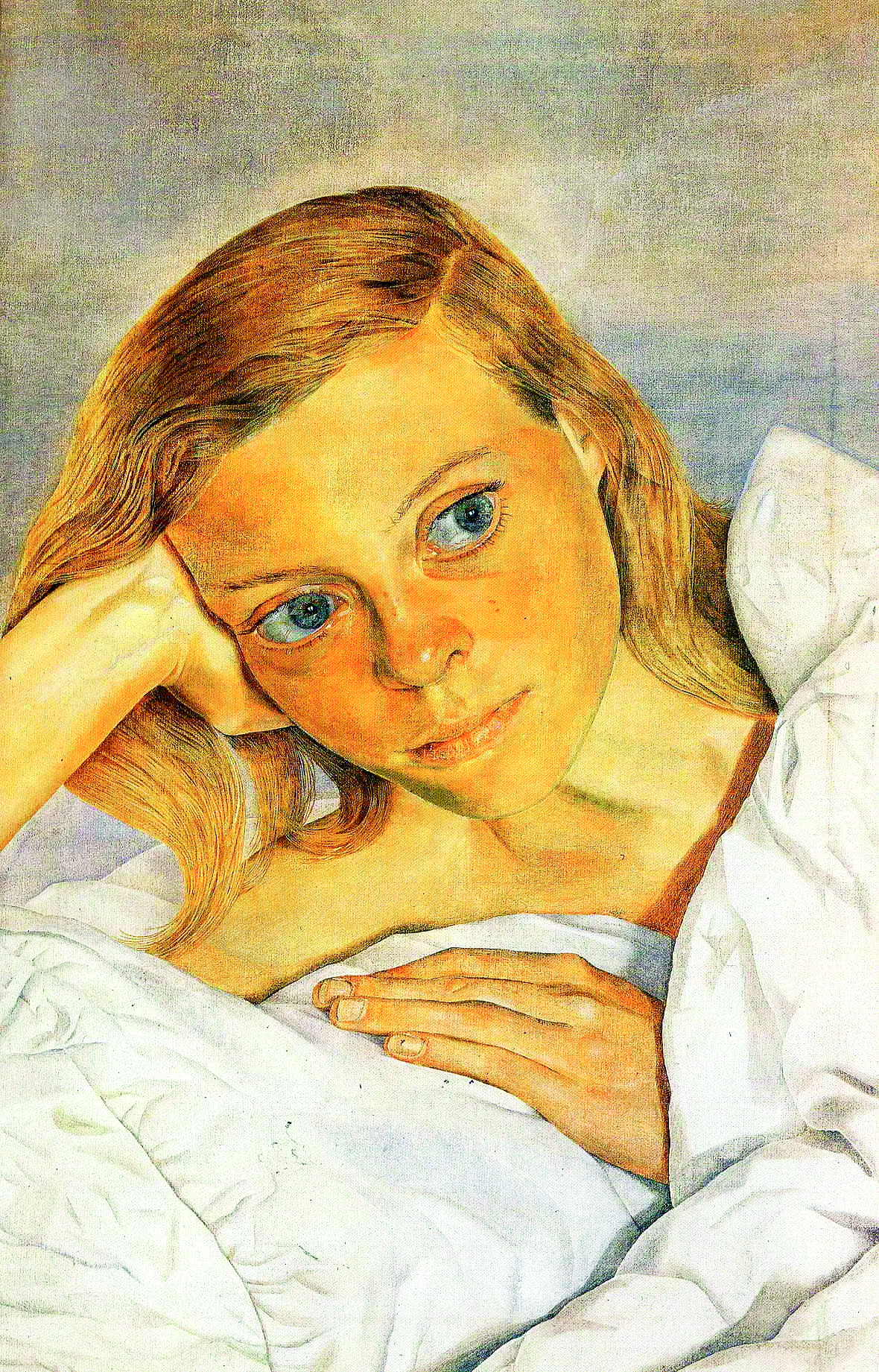

THE UNNAMED NARRATOR of Small Rain will be familiar to readers of Garth Greenwell’s What Belongs to You and Cleanness: poet, teacher, expat, gay. Those two books of fiction trace the poet’s life in Bulgaria, where he teaches English literature to high schoolers, though a difficult childhood under a violent patriarch in Kentucky intrudes on […]

- print • Fall 2024

I DON’T REMEMBER WHEN I first heard the term “incel” but I do recall my reaction: I don’t want to know about these guys. You feel sympathy for lonely people, of course, but it would seem that their constitution as a class or identity category in the internet age, while perhaps inevitable, can only compound […]

- print • Fall 2024

RIOTS IN PARIS GRAB THE HEADLINES, but the real radicalism in France happens in the countryside. Take the zone à défendre, or ZAD, in Notre-Dame-des-Landes. What began in 2012 as a farmer’s protest against the construction of an airport turned into a successful squatter campaign that drew allies from environmental and anarchist groups across the […]

- print • Fall 2024

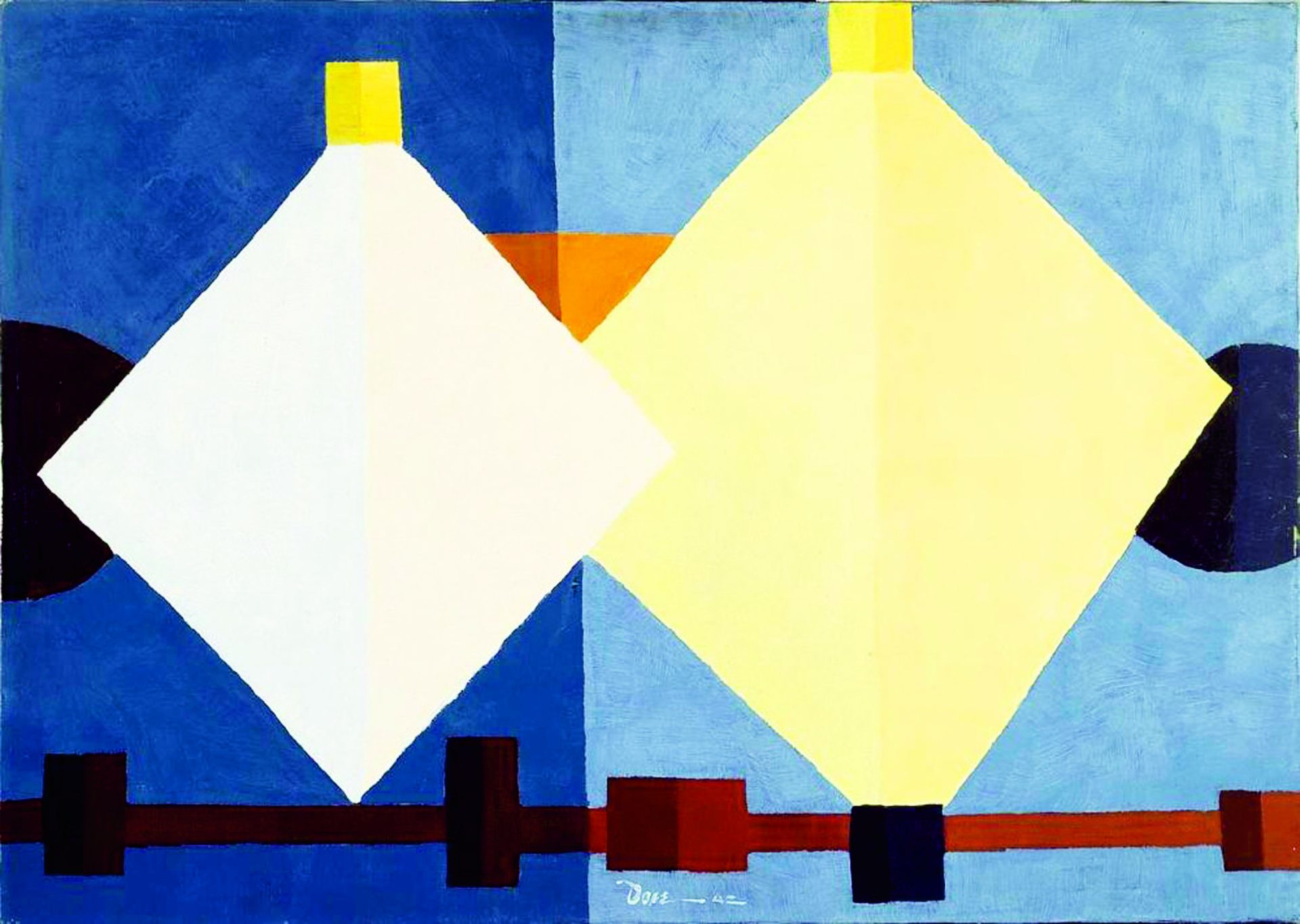

THE DEFINITION OF INSANITY, as the cliché goes, is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results, yet American intellectuals have been founding little magazines since at least 1840, when a group of Transcendentalists published the inaugural issue of The Dial—often cited as the progenitor of the form on this side […]

- print • Fall 2024

OVER THE COURSE of two seasons of the TV sitcom Mixed-ish, a spin-off of ABC’s eight-season hit Black-ish, biracial protagonist Rainbow Johnson tries to adapt to regular life after a childhood spent in an idyllic race-blind hippie commune. In episode after episode, innocent Rainbow encounters confusing, contradictory examples of how race operates in the mainstream […]

- print • Fall 2024

I AM NOT SAYING that I conjured a new Sally Rooney novel, but last year, I posted on X, formerly known as Twitter, “I know she just published a book, but like . . . when is Sal Roones coming back. I need her,” and a few months later, it was announced that she would […]

- print • Summer 2024

BEFORE READING GABRIEL SMITH’S DEBUT NOVEL BRAT, I did the normal thing and googled him. I thought I remembered seeing his name on my Twitter feed: in February, Smith had posted a screenshot of a hoax email from Charli XCX, in which she divulged that she was “a HUGE fan” of his writing and asked […]

- print • Summer 2024

MARRIAGE IS A GRIM BUSINESS—worse still if you’re a woman in a Rachel Cusk book. The blame lies with Christian iconography, she writes in her 2012 memoir, Aftermath, and pictures of the “holy family, that pious unit that sucked the world’s attention dry.” There, we found Mary and the manger, the Christ child, cuckolded Joseph: […]

- print • Summer 2024

SHEILA HETI: Your new novel, Help Wanted (W. W. Norton, $29), is about the collective action of a group of workers at a big-box store. They try to get their hated boss out of their hair in a way that is counterintuitive and comic. It feels completely different from your 2013 book, The Love Affairs […]

- print • Summer 2024

IN THE PROLOGUE TO CLAIRE MESSUD’S This Strange Eventful History, the unnamed narrator goes to see a witch, a “clairvoyant,” while on holiday in some seaside New England town: Though I told her I was a writer, she insisted that I was a healer; once she said it, I willed it to be true. Or: […]

- print • Summer 2024

IN THE FIRST PAGES of All Fours, Miranda July’s second novel, the unnamed narrator confesses to collecting intimate ephemera from her friends’ relationships. But the “artifacts”—“screenshots of sexts, emails to their mothers,” recordings of conversations—never add up to something substantial. Her impulse to acquire these relics is “like trying to grab smoke by its handle,” […]

- print • Summer 2024

IN HARI KUNZRU’S NOVEL My Revolutions (2007), which starts in Britain in 1998, the narrator, a fifty-year-old named Michael Frame, receives a visit from an old friend, Miles, the only person who knows that he is a former violent radical living under an assumed identity. To the delight of Michael’s younger wife and late-adolescent stepdaughter, Miles reels […]

- print • Summer 2024

IF THE MEASURE of a debut is how capably it shits on the pieties of its literary forebears, then Honor Levy’s funny, provocative My First Book is an unqualified success. The fact that I, an Elder Millennial, found it largely inscrutable proves the point. Though nominally fiction—at least according to the metadata—the sixteen pieces collected […]

- print • Summer 2024

OPEN ANY BOOK BY CAROLINE BLACKWOOD and you will encounter the same woman. Articulate, adrift, callous, cosmically self-absorbed. She’s in the middle of her life, a retired actress or model, once striking and sought-after. Her misery has a predatory quality. Decisions made idly and capriciously she now clings to as essential facets of her “character.” […]

- print • Summer 2024

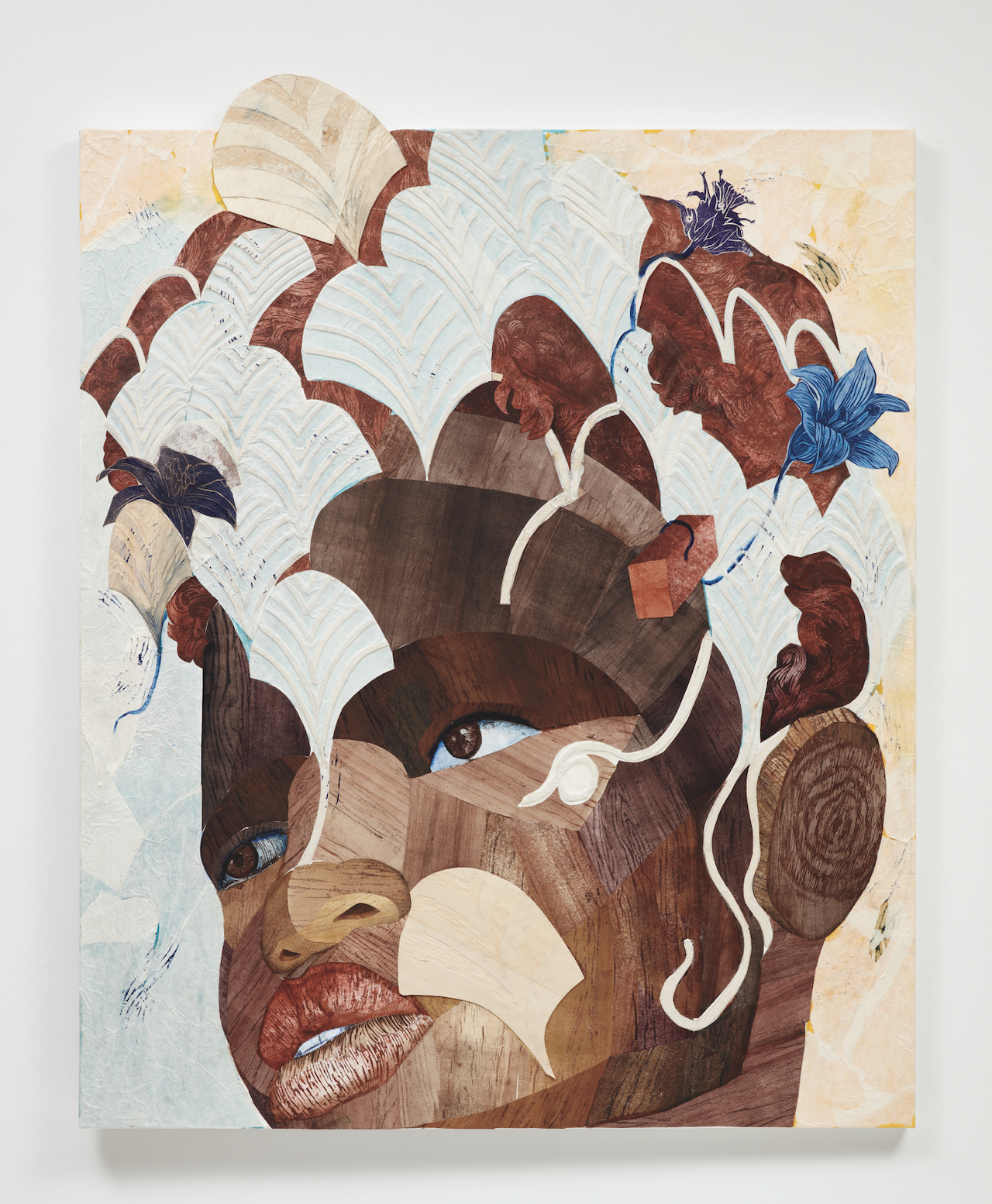

KARL KRAUS WROTE THAT EVERYTHING FITS WITH EVERYTHING ELSE. Maybe. Maybe everything in an artist’s corpus, no matter how incongruous, reflects, repeats, rhymes. Yet this is not the case for Percival Everett. No thematic or formal schema is suitable. He climbs the stairs sideways. His patently ridiculous conceits seem like challenges to his own mischievousness, […]

- print • Spring 2024

MEET THE CAST: David Crader, a washed-up child actor, author of the celebrity memoir that constitutes the bulk of Justin Taylor’s second novel, Reboot; Amber, David’s long-suffering second ex-wife, mother of his child, in whose life David appears, in his own words, as “an occasional cameo”; Grace Travis, David’s first ex-wife and former costar, diversifier-of-portfolio par excellence (“We can’t all be Gwyneth or Busy,” Grace says, “but we do what we can”); Shayne Glade, David’s best frenemy and former costar, a buffer and more talented foil; Molly Webster, culture writer, bartender, holder of an MFA in “speculative nonfiction”; Corey Burch, once

- print • Spring 2024

HELEN OYEYEMI’S NEW NOVEL Parasol Against the Axe, set amid a bachelorette party weekend in Prague, abounds in side quests breezily undertaken and abandoned. You don’t need to think about the bachelorette party all that much. Actually, you can’t. The rate at which Oyeyemi invents thickets of problems without answers, obstacles to bounce over, mysteries to shrug at, is frantic, like in those dreams where you have to run very fast in order to move slowly.

- print • Spring 2024

LO. LEE. TA. This is the trip the tip of the tongue expects to take when reading a novel from the point of view of a man currently incarcerated following the rape of a teenage girl he’s groomed. And at the tender age of thirteen pages into Lucas Rijneveld’s My Heavenly Favorite, an attentive reader may indeed murmur “Lolita!” when the unnamed narrator, a former farm veterinarian from the Dutch countryside, refers to the titular “favorite,” also unnamed, as “the fire of my loins.” So far, so Lo.

- print • Spring 2024

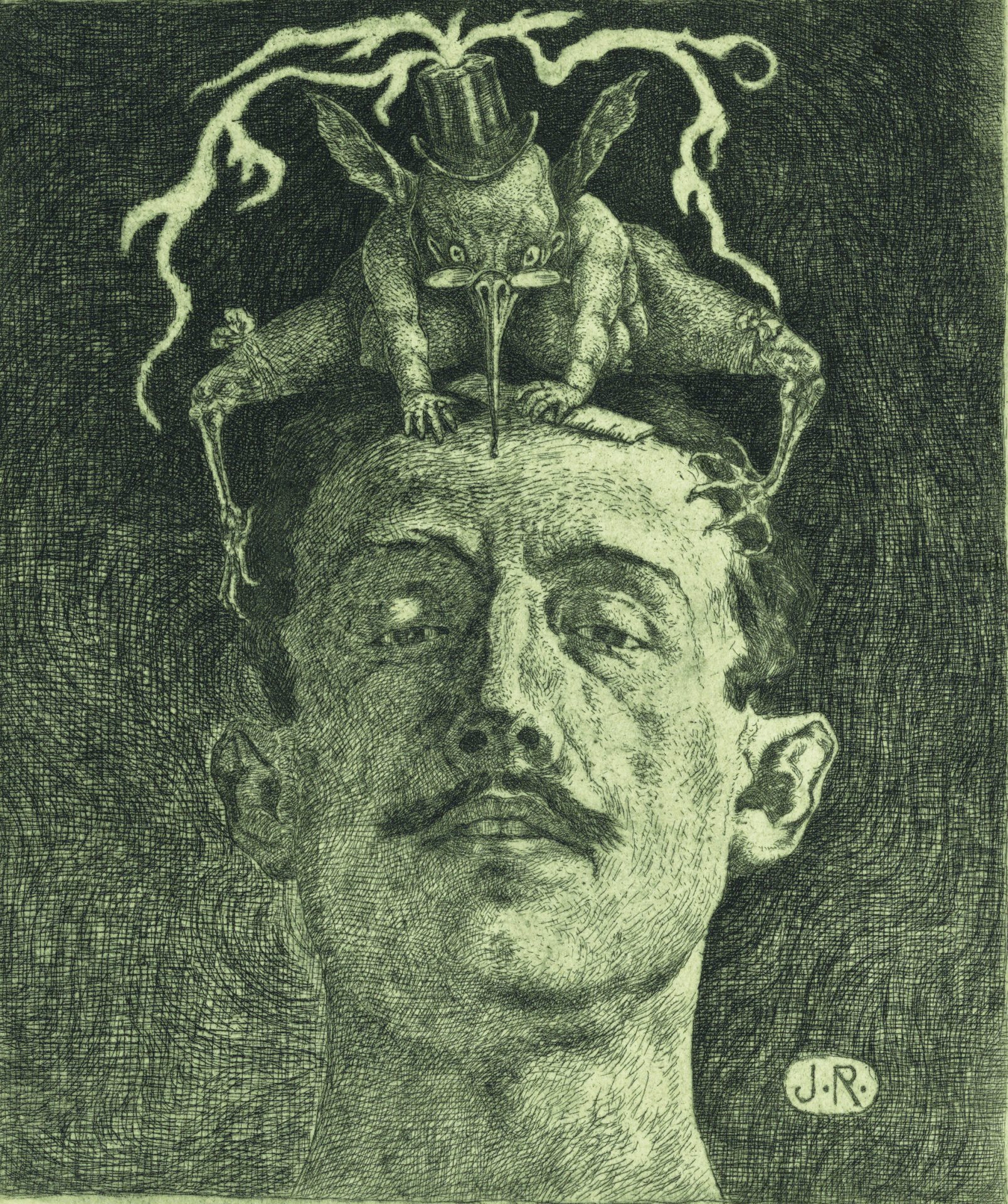

THE DILIGENT Prussian bureaucrat E. T. A. Hoffmann had a mischievous double. By day, he worked as a jurist in the courts of present-day Poland and Germany; by night, he wrote impassioned music criticism in the voice of his alter ego Johannes Kreisler, a tempestuous composer who also appears in several of Hoffmann’s stories and novellas. The wild cry that rings out in his first novel, The Devil’s Elixirs (1815), could just as well describe his own adventure in bifurcation: “I am what I seem to be, yet do not seem to be what I am; even to myself I am