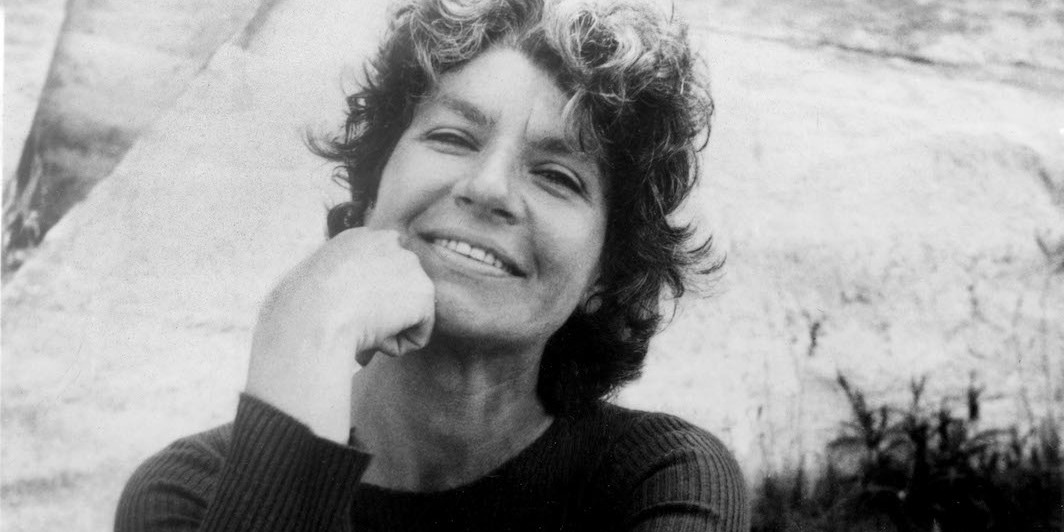

Unlike her character Sibylla, Helen DeWitt did successfully complete her degree. She won the prestigious Ireland Prize for young classicists and might have been able to make a career in the academy. Oxford University Press wanted to publish her dissertation. But DeWitt decided to leave. She didn’t leave, or didn’t only leave, because Oxford failed to live up to her fantastic standards. She also left because she discovered an alternative to the academic pursuit. In graduate school, she recalls, “a British Jew introduced me to Kurosawa and Sergio Leone and Dennis Potter, to the power of imaginary Americas.” That “British

- • October 27, 2022

- • October 13, 2022

“The Foot of the Tan Building” A woman jumped from the top floor of a Northeast Bronx building, from the 33rd floor of a building, at around 10:40 in the morning (10:40 am, a time that seems too early to jump from anything at all). The woman might have recently lost a child. The photograph online shows the body at the foot of the tan building, near a patch of grass. Under a white sheet—a waiting body. Before the woman’s final decision she might not have considered the possibility of this white sheet, its thinness, or how it would not

- • October 7, 2022

Stephanie LaCava’s second novel, I Fear My Pain Interests You, opens with a strange epigraph: “Cows are not sentient beings.” The quote is attributed to “Reddit”—not a specific person on Reddit, but the platform itself, the amorphous, faceless chorus of fifty-two million very opinionated daily active users. It’s an enigmatic piece of front matter for an enigmatic story, and one that successfully primes the reader to enter the world of LaCava’s protagonist, Margot Highsmith, who, in a way, lacks sentience of her own.

- • September 27, 2022

Jem Calder’s Reward System is a fractionated fiction for a fragmented world: one in which the means of connection are constantly available, but connection is harder than ever, and everything is linked, but little is shared. The book, Calder’s debut, consists of six “ultra-contemporary fictions” that center on two characters, Julia and Nick, old university friends and one-time lovers whose post-university years are dominated by work and technology. Calder flits between episodes in their lives, magnifying specific incidents, leaving the reader to string together a narrative from discrete stories. Just when you’re getting comfortable, the scene shifts, or the characters

- print • Sep/Oct/Nov 2022

IN A VIRAL VIDEO from last October, Jamie Lee Curtis repeats the word “trauma” ad infinitum on the press circuit for Halloween Kills. The comedy comes partly from Curtis’s unorthodox pronunciation—trow-muh, not trah-muh—but also from the supercut’s temporal absurdity, how a word uttered repetitively and uninterruptedly misplaces meaning. The context of the slasher flick raised additional hackles: we’ll exploit trauma to elevate just about anything. The video appears, in hindsight, to be an early indicator that the tides were turning: now there was a slapstick, tacky sensibility to trauma’s discursive hypersaturation. As The Body Keeps the Score became memeified, critics

- print • Sep/Oct/Nov 2022

THERE ARE A LOT OF OLD FLAMES in Gwendoline Riley’s 2017 book First Love. The novel begins where so many end—in marriage, with its protagonist Neve moving into her husband Edwyn’s flat in London. What looks like the prelude to the sweet life—two lovers easing into domestic settlement—soon turns sour. There are pet names, and then there are “other names, of course.” On page two, we learn that Edwyn once called Neve “a fishwife shrew with a face like a fucking arsehole that’s had . . . green acid shoved up it,” among other things. It only gets more rancid

- print • Sep/Oct/Nov 2022

MUST A NOVEL ENGAGE with contemporary life? One still finds the call, as tenacious as cliché, for novels that “speak to the moment we are in,” “work out society,” or otherwise “interpret the now,” insisted upon regularly in marketing copy and pieces of criticism, not to mention on Twitter. A better question to ask is whether a novel can do anything but react to—or reflect—contemporary life. This one is characteristic of a certain kind of Marxist criticism, which seems at times to make a point of noting that novels engage with the “now” regardless of their authors’, or readers’, intentions.

- excerpt • July 25, 2022

“Reality is not a given: it has to be continually sought out, held—I am tempted to say salvaged,” John Berger writes in his 1983 essay “The Production of the World.” “Reality is inimical to those with power.”

- review • July 22, 2022

The narrator of Jordan Castro’s debut novel, The Novelist, is a writer and a recovering heroin addict. Newly sober, he feels as if he’s seeing the world for the first time, and all the ordinary things he overlooked as an active addict are now taking on a surreal quality—the way the light plays on the bedroom wall alone seems to be too much. He is trying to write a novel about his once-humorous, pathetic life as an addict, except he is now driven by a more common addiction: checking Gmail and scrolling through Twitter. Sobriety gives him a new existence,

- review • July 14, 2022

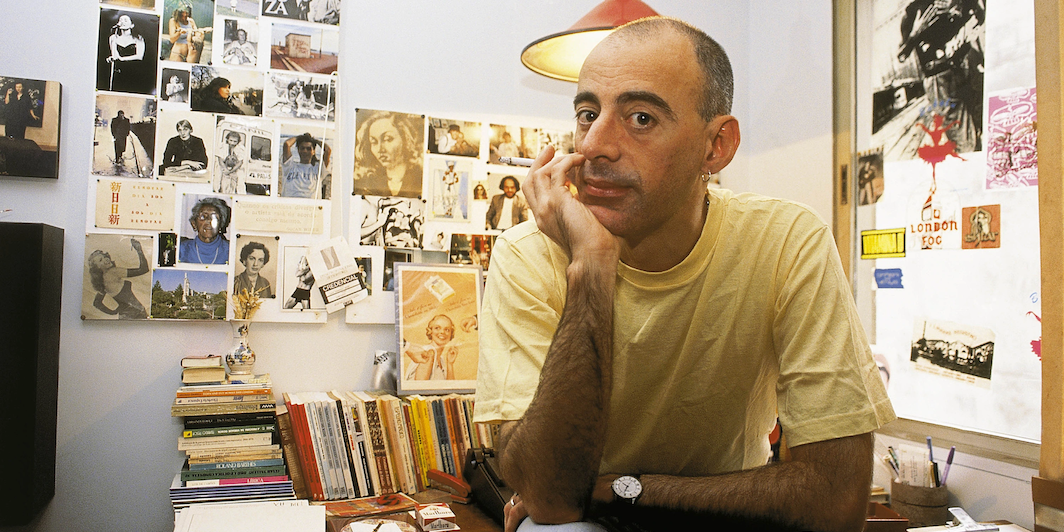

The austerity of painting stripped down to reveal the threadbare lives of the artists; domestic strife heighted to the point of sublimity; personal memoir caressed by the ancient lunacy of myth; comic-book characters trespassing at the gates of high modernism; the love of books and cats. Frederic Tuten’s trajectory through letters has been uncategorizable, heteroclite, and consistently at odds with the prevailing fashion—so much so that he comes across less as a member of any extant school of literature and more as a Dada or Pop artist who happens to work primarily with words. His new story collection, The Bar

- review • July 1, 2022

A FRIEND OF MINE from what feels like a lifetime ago once introduced me to her uncle during dinner at her mom’s house. That he was avuncular in all the classic ways—huge, meek, seemed like he had a life defined by extreme silence—was mostly unremarkable, but what lingered from our meeting was his decision to forcibly share his two clearest, greatest fantasies with a table largely made up of children. The first, he said, extending a finger over some entreé meat, was to meet supermodel Christie Brinkley before he faced the grave. The other—up went another finger, eyes and heart

- excerpt • June 27, 2022

It’s always been a sport to argue about the canon. I’ve never been one for sports.

- excerpt • June 14, 2022

She is biting her nails when I open the door, her purse pressed tightly against her breasts. As usual, I think as she walks in, head down, and sits in her usual place, Mondays and Thursdays, five o’clock: as usual. I shut the door, walk over to the armchair in front of her, sit and cross my legs, making sure I pull up my pants first so they won’t have those awful creases on my knees. I wait. She doesn’t say anything. She seems to be staring at my socks. Slowly, I pull a cigarette out of the pack in

- print • June/July/Aug 2022

EARLY IN ELIF BATUMAN’S NEW NOVEL Either/Or, she quotes a blurb on the front of Kazuo Ishiguro’s An Artist of the Floating World, extracted from its 1986 review in the New York Times. “Good writers abound—good novelists are very rare,” the critic theorizes, deeming Ishiguro “not only a good writer, but also a wonderful novelist.” For Either/Or’s narrator, the distinction comes as a shock. Since she was young, Selin has aspired to become a novelist, and she views much of her life to date as training for that vocation. Assessing herself according to the reviewer’s implied rubric, Selin realizes that

- print • June/July/Aug 2022

A SPECTER IS HAUNTING AUTOFICTION. The specter of ripping off your life for your novel and not making a whole goddamn thing about it. Elizabeth Hardwick’s unnamed narrator spent her Sleepless Nights in Elizabeth Hardwick’s apartment and it worked out fine for both of them. Roth had Zuckerman and, later, “Roth,” and later still Lisa Halliday had “Ezra Blazer.” There have been abundant Dennises Cooper, Joshuas Cohen, and Dianes Williams. Sebald and Bellow—just saying the names should be enough. Jamaica Kincaid gave Lucy her own birthday. Then you’ve got the New Narrative movement of the ’70s and ’80s, plus a

- print • June/July/Aug 2022

PUBLISHED IN 1974, Patricia Nell Warren’s best-selling novel The Front Runner, about the same-sex intergenerational romance between Harlan Brown, a college track coach, and Billy Sive, his star athlete, capitalized on dual booms from that decade: the running craze and the growing crossover appeal of LGBTQ+ literature.

- print • June/July/Aug 2022

ON APRIL 12, Joyce Carol Oates, who’s had a surprise second act as a social-media provocateur, tweeted, “Much prose by truly great writers (Poe, Melville, James) is actually just awkward, inept, hit-or-miss, something like stream-of-consciousness in an era before revising was relatively easy.” Like much Tweeting by truly great Tweeters, Oates’s hot take struck a nerve because it reflected the zeitgeist; whatever one’s feelings about the nineteenth-century masters, one must concede the current vogue for tightly structured novels, rendered in lucid, well-modulated prose. For a long time now, American fiction has not been characterized by any one school or approach,

- print • June/July/Aug 2022

IN 2014, the novelist and essayist Cynthia Ozick reviewed the collected fiction of Bernard Malamud for the New York Times. Ozick adores her slightly older contemporary for his bruised moral seriousness. The essay contains just one asterisk: “The reviewer has not read and is not likely ever to read ‘The Natural,’ a baseball novel said to incorporate a mythical theme. Myth may be myth, but baseball is still baseball, so never mind.”

- review • May 5, 2022

Six-year-old Marina Salles dubs her grandmother’s house on the salt-swept Monterey Peninsula “the Plastic Palace.” Protective runners cover the carpets and kitchen table, encased and safeguarded from spills. The Plastic Palace is a special nickname, something shared between Marina and her mother, Mutya, who are living there with her grandmother, Lola Virgie, in 1982. Love, here, peeks out from corners: from the “sharp tips” of the plastic, from Lola’s routines and regimens. Mutya evades domestic responsibilities, spending weekdays at college and leaving Marina in Lola’s care.

- review • April 28, 2022

I spent the last days of 2019 with family in a Panamanian duplex, across the street from a “village” of high-end apartments where men worked the yards. Fernanda Melchor’s new novel, Paradais, takes place at a Mexican luxury development that shares the Panamanian complex’s name: Paradise. The coincidence is banal, if illustrative. “Páradais,” the phonetic rendering of an English word, is a clichéd, empty signifier of colonial “luxury,” sort of like an American apartment complex called “Royal Glen” or “High Manor.” But Melchor’s novel owes less to the unimaginative naming conventions of developers than to its chief intertext: José Emilio