Genevieve Hudson. Photo: Thomas Teal Genevieve Hudson’s debut novel, Boys of Alabama, tells the story of Max, a shy German teenager with a rare magical power, who emigrates with his parents to Alabama (Hudson’s own native state). There, Max finds a place rife with wonders and terrors beyond anything he’s ever known. It’s a slow-burning exploration of queerness and magic and toxic masculinity—of otherness and the yearning to belong—set against the landscape of the Deep South. During the early days of the lockdown, Hudson and I talked about obsession, sentences that are more than mere load-bearing devices, and the

- interviews • August 18, 2020

- interviews • August 10, 2020

Algiers, Third World Capital by Elaine Mokhtefi Born in New York, journalist and artist Elaine Mokhtefi became active in the youth movement for peace and justice in the early ’50s. In 1951, she went to Paris, where she first became aware of France’s colonial involvement in Algeria, and in 1962 she moved to Algiers to work in the newly independent Algerian government. Algiers, Third World Capital captures the author’s experiences in Algeria after its liberation from French colonial rule; her interactions with figures there such as Frantz Fanon, Stokely Carmichael, Timothy Leary, Ahmed Ben Bella, Jomo Kenyatta, and Eldridge

- interviews • August 3, 2020

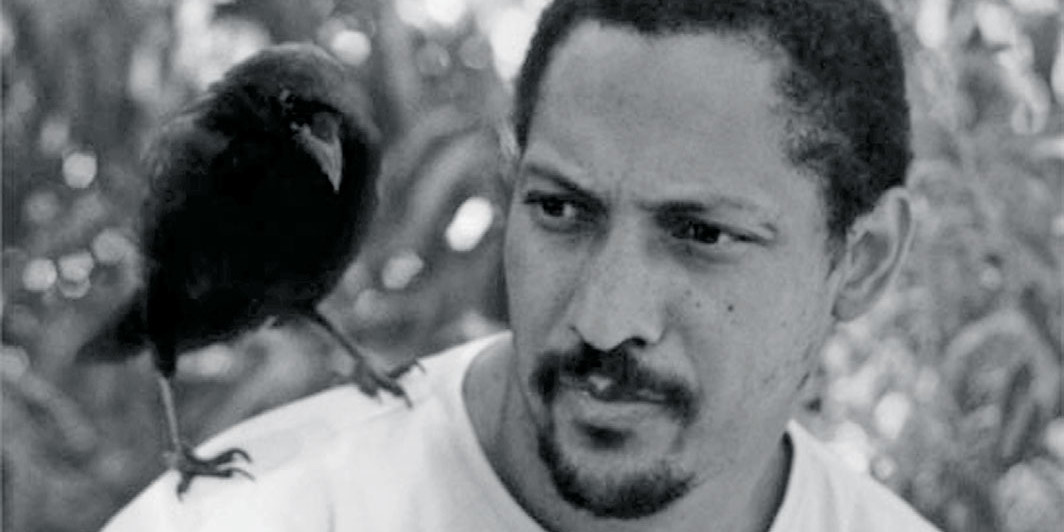

Adam Levin. Photo: © Renaud Monfourny One thing I like about Adam Levin’s novels is that they take over your life for a time. They’re very large, but their immersive nature is mostly due to Levin’s idiosyncratic weirdness. His 2010 debut, The Instructions—a thousand-plus-page novel told from the perspective of a precocious ten-year-old Jewish boy with messianic tendencies—was followed by a short story collection in 2012, Hot Pink. Now there is Bubblegum, a nearly eight-hundred-page novel narrated by a thirty-eight-year-old man named Belt Magnet, an amateur memoirist who has long, private conversations with inanimate objects. Set in an alternate

- interviews • July 27, 2020

Laura van den Berg. Photo: © Paul Yoon Laura van den Berg writes ghost stories: In her new book, I Hold a Wolf by the Ears, absences assume a life of their own, demanding to be acknowledged. The dead, the forgotten, and the lost have a shimmering vibrancy, becoming more present than the real. Like her ghostly figures, van den Berg comes home in this collection. Short stories were her first literary love, and I Hold a Wolf by the Ears is her return to the form after two successful novels. The book also represents a more literal homecoming.

- interviews • July 16, 2020

Interior view in lantern of lighthouse of Fresnel lens – Split Rock Lighthouse, Off Highway 61, 38 miles northeast of Duluth, Two Harbors, Lake County, MN. Photo: Lowe, Jet/Library of Congress A longtime translator, Christina MacSweeney is responsible for bringing the writing of authors like Valeria Luiselli, Daniel Saldaña París, Verónica Gerber Bicecci, and Eduardo Rabasa to English-language readers. She is drawn to works that exists outside the confines of a single genre, especially those that merge the visual and literary. The latest addition to this impressive ensemble is Jazmina Barrera’s On Lighthouses, a delightful, pocket-sized book chronicling Barrera’s

- interviews • July 9, 2020

Alexandra Chang. Photo: Alana Davis In Alexandra Chang’s debut novel, Days of Distraction, the twenty-five-year-old narrator escapes her unfulfilling job as a tech reporter by moving from her native San Francisco to upstate New York with her longtime boyfriend. On their road trip across the country, she begins to question her relationship with J., who is white. Once they settle in Ithaca, the narrator finds herself feeling increasingly distant from her boyfriend, and spends her time collecting forgotten pieces of Asian American history and working in the archives of a historical museum. Dissatisfied with Ithaca, she heads to China,

- interviews • June 25, 2020

Jean-Patrick Manchette, Self-portrait from 1964, © Estate of Jean-Patrick Manchette After the protests of May 1968, Jean-Patrick Manchette began writing a cycle of hard-boiled romans noirs. Involved with the French ultra-left since his adolescence, Manchette aimed to rehabilitate the genre. Steeped in American crime fiction, Manchette’s work imported the Situationist critique and other ultra-left discourse into what was then considered perhaps the lowest of all mass-produced literature. Translator Donald Nicholson-Smith has done more than anyone else to bring Manchette to English-language readers. Last summer, New York Review Books Classics published Nicholson-Smith’s translation of Nada, a story about kidnapping, anarchist

- interviews • June 11, 2020

Tracy O’Neill. Photo: Oskar Miarka So, where does Quotients, this big, multilayered novel, come from? Quotients is about people trying to build homes and find shelter in family, when they feel that the world is place full of peril. This was a preoccupation in my own life. Then, I met a man who said he’d once been a spy. Spying is motivated by a desire to keep some “us” safe through gathering information and forming predictions, but it introduces danger, too. It’s predicated on the fear that things may not be what they appear to be, but it also

- interviews • June 2, 2020

Wayne Koestenbaum. Photo: Tim Schutsky Wayne Koestenbaum performs a surgery of surfaces. He finds the inside of a thing by drawing together the outsides of that thing, pinching the body until the folds present a name. His new book, Figure It Out, is a collection of essays and reviews written at some point in the twenty-first century, mostly the last ten years. The thread of the book is “Wayne thought it” and this glistens like a shell. These pieces are self-assignments, opportunities to create and solve a problem at the same time. Some tell you this right up front.

- print • Summer 2020

In your new novel, A Children’s Bible (Norton, $26), a group of kids, teens mostly, are on vacation with their parents in an old mansion when a flood occurs and American society begins to fall apart. Would it be fair to call it a soft apocalypse, or a plausible dystopia?

- interviews • May 13, 2020

Lucy Ives Madeline Gins (1941–2014) never took anything for granted, certainly not something as foundational as language. Gins was a philosopher, writer, agitator, and architect. She is probably best known for her project Reversible Destiny, an elaborate philosophical endeavor she developed with her husband, the artist and architect Shusaku Arakawa, that questioned the inevitability of death. Over the course of several decades, beginning in the 1960s—often in collaboration with other artists, scholars, and architects—Arakawa and Gins conducted research, made art, wrote manifestoes, and designed and constructed buildings that they believed could extend inhabitants’ lives. Calling into question the fixed

- interviews • May 5, 2020

Celia Laskey. Photo: Leonora Anzaldua Celia Laskey’s new novel, Under the Rainbow, takes place in the fictional town of Big Burr, Kansas, which could easily stand in for any small town in America. Like the town Laskey herself grew up in, Big Burr is full of people who love each other, while also being insular. After LGBTQ+ rights group Acceptance Across America determines that Big Burr is “the most homophobic town in America,” the group sends a cohort of queer people from the coasts to change hearts and minds. Under the Rainbow follows several characters over the AAA’s two-year

- interviews • April 14, 2020

Chelsea Bieker. Photo: Jessica Keaveny Chelsea Bieker grew up in California’s Central Valley, where agriculture and survival are intertwined, a landscape that leaves its mark on her debut novel, Godshot. Fourteen-year-old Lacey May lives with her mother in the fictional town of Peaches, California. The grape-growing industry, the town’s main employer, has been ravaged by drought. Enter Pastor Vern, a glitter-loving cult leader who exploits this desperation by promising that God will bring rain if the townspeople join his church, Gifts of the Spirit. Almost all the residents of Peaches are drawn in to the group, including Lacey and

- interviews • April 7, 2020

Malcolm Harris. Photo: Julia Burke One of the most striking, important, and unique features of Malcolm Harris’s work is the way in which he integrates a profound understanding of Marx’s critique of political economy into his analyses of our contemporary life without heavy-handed jargon. Harris’s first book, Kids These Days: Human Capital and the Making of Millennials (2017), addressed how we should understand millennials and explains why we shouldn’t understand their generation in terms of the moralizing analyses that are often proffered but instead in terms of its mode of production. His new book, Shit is Fucked Up Bullshit:

- interviews • March 31, 2020

Eve Babitz. JULIA PAGNAMENTA: In the preface to your first book, Eve’s Hollywood (1974), you write, “I believe that places should be capitalized . . . West, especially, is a serious place that should ALWAYS be capitalized. It also sounds more adventurous to go West than to go west.” The spirit and sense of a place—genius loci—are such prominent parts of your writing. How does sense of place influence your writing? EVE BABITZ: I was a visual artist first, my collages and drawings, and I really like the way certain words look, like West rather than west. I love

- print • Apr/May 2020

Greil Marcus: Starting in 1983 with Suder, you’ve published, I think, twenty-five books of fiction. In your new novel, Telephone (Graywolf, $16), the narrator is a geologist; one day, playing chess with his twelve-year-old daughter, she misses a move—and soon she is diagnosed with a disease that in a short time will destroy her mind and then her life. He can’t save her—but one day he finds a note in a shirt he’s ordered online, from New Mexico, reading “Help me” in Spanish. He places another order; another note, speaking for more than one person. He can’t save his daughter—maybe

- interviews • March 19, 2020

Emily Nemens. Photo: James Emmerman Emily Nemens, the editor in chief of the Paris Review, is also an accomplished illustrator: Her cartoons have appeared in publications like the New Yorker, and in 2011 she started a multiyear series of watercolor portraits of every woman in the 112th, 113th, and 114th Congresses. Nemens also happens to know a lot about baseball, thanks to a childhood spent watching Mariners games with her father in her native Seattle. Each of these skills comes into play in Nemens’s new novel, The Cactus League, a propulsive debut set in the highly competitive world of

- interviews • February 17, 2020

Fanny Howe. Photo: Lynn Christoffers Born in 1940 during a lunar eclipse, the poet and novelist Fanny Howe is the black sheep of her blue-blooded Boston family. Daughter of Mark DeWolfe Howe, a Harvard law professor and civil rights activist, and Mary Manning, an Irish-born actress and playwright, Howe grew up as part of a powerful and gifted artistic pantheon. Breaking with tradition, she moved West, became a communist and later a Catholic, and dropped out of college three times. (Howe attended but never graduated from Stanford.) She eloped with a conservative microbiologist but left him in the febrile

- interviews • February 4, 2020

Carson McCullers. Photo: Carl Van Vechten, 1959. Library of Congress, Prints Photographs Division, Carl Van Vechten Collection. In 2012, Jenn Shapland was an intern at the University of Texas’s Harry Ransom Center. While working there, she discovered the archives of Carson McCullers, the inspiration for Shapland’s new book. She had never read any of McCullers’s work, but the titles, Shapland writes in the first pages of My Autobiography of Carson McCullers, “always struck a chord with me. The Heart is a Lonely Hunter. Like, same.” One day, as Shapland was answering queries from researchers and scholars, she came across

- interviews • January 30, 2020

Anna Wiener. Photo: Russell Perkins Silicon Valley has mostly been chronicled by founders, investors, and tech-utopian true believers. By that measure, Anna Wiener’s new memoir of working for start-ups, Uncanny Valley, in not really an insider’s account. True, Wiener worked for a variety of tech companies beginning in 2013, but her customer-support jobs were viewed as superfluous to the “real” work of CEOs and engineers. This position of insider-outsider allowed Wiener to impartially observe the hidden workings of companies that have taken over virtually every aspect of the economy and transformed our public and private lives. Bookforum spoke to