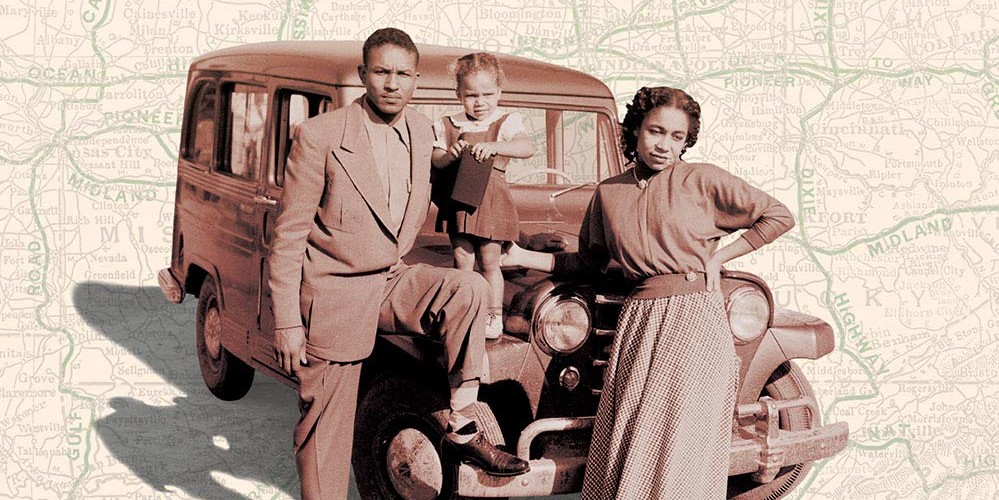

The signage of segregation, terrible and tangible, left us with a deficient vision of Jim Crow America. The cruelty of a whites only placard may seem like the bookend to Bull Connor’s gross brutality, but such signage implied that the dangers and humiliations of Jim Crow always came labeled. White supremacy drew its power from the ritualized humiliation of black people having to ask if a public service was available. Even sundown towns—communities across the nation that violently banned African Americans after dark—didn’t always advertise their own rules. For mid-twentieth-century black Americans, the Green Book travel guide was a potentially

- print • Dec/Jan 2020

- review • November 14, 2019

Monopolies have long been a fixture of American life. Since the 1980s, when Ronald Reagan’s free-market policies reshaped the economy, they have become especially persistent. Today, companies with outsize market shares—from Big Tech and large investment banks to retailers and food conglomerates—dominate the US economy. The doctrine incubated by Milton Friedman and others at the University of Chicago, which emphasizes economic efficiency and deregulation, continues to prevail. This laissez-faire approach, presented in Friedman and Anna J. Schwartz’s A Monetary History of the United States, 1867–1960, a bestseller during the waning days of the Kennedy administration, led to a legal reversal

- review • October 3, 2019

“Are we going to burn it?” A question about the fate of the future concludes Hazel Carby’s Race Men (1998), a powerful academic book about suffocating representations of black American masculinities based on a lecture the author delivered at Harvard. In her newest book, Carby is already burnt, the result of a smoldered past. “Imperial Intimacies is a very British story,” she writes in the preface. It is also her story: about growing up after World War II, about her childhood in the area now known as South London, about the family histories of her white Welsh mother and black

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2019

TAKE A MINUTE NOW to write down the first associations that come to your mind regarding Clarence Thomas. You might note that he represents the extreme right wing of the Supreme Court and that, beginning his twenty-ninth term this fall, he is its longest-serving justice, not to mention Donald Trump’s personal favorite. No doubt you’ll think of his alleged sexual harassment of Anita Hill during his tenure at the Department of Education and when he was head of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission under Ronald Reagan, of the ordeal she went through when forced to testify about it during his

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2019

When Americans talk about inequality, we prefer to skip over an important foundational question: Are richer people better than poorer people? In general the unspoken assumption is yes. Conservatives tend to believe richer people are better because capitalism is designed to reward goodness: Thrift and hard work make wealth, so wealthy people must be thrifty and hardworking. Liberals tend to believe richer people are better because capitalism provides them with more opportunities and access to experience, while poorer people are on average deprived of good education and international travel.

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2019

Ebola “begins as a mystery story,” as the science writer David Quammen puts it in his excellent 2014 primer Ebola: The Natural and Human History of a Deadly Virus, which expands on a chapter from Spillover, his enchanting study of zoonotic diseases. Every new infectious disease is a mystery, of course, but the dramatic efficiency with which Ebola kills—it is highly lethal and infective, causes hemorrhagic fever, and has a brief incubation window—lends it an apocalyptic aura. Indeed, science writer and New Yorker contributor Richard Preston introduced The Hot Zone—his best-selling 1994 account of “The Terrifying True Story of the

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2019

As the earth melts, societies age, and economies slow, a narrative of humanity’s inevitable decline has settled in and calcified. It seems as though there’s no story left to tell but that of a slow descent into a gray future beset by any number of catastrophes. To hear pronatalists tell it, many of these will happen because we aren’t having enough babies. Fertility rates have hit an all-time low in the United States. For conservatives, this spells doom for all manner of American traditions: Social Security, masculinity, a robust economy, even democracy itself. New York Times columnist Ross Douthat has

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2019

All four of Nicholas Lemann’s major books examine crucial episodes of American history through the prism of lives that shaped or were shaped by that history. In 1991’s The Promised Land, Mississippians Ruby Lee Daniels and George Hicks embody the Great Migration as they relocate to Chicago. In 1999’s The Big Test, the Educational Testing Service’s Henry Chauncey and Los Angeles attorney Molly Munger carry Lemann’s analysis of an SAT-fueled meritocracy more privileged than it knows. Redemption’s alarming and often brutal 2006 account of racist terrorists destroying Reconstruction makes flawed heroes of Maine-born Union general turned Mississippi governor Adelbert Ames

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2019

In 2009 Mohamed Nasheed, the president of the Maldives, the island nation sinking into the sea, put on a wet suit and an air tank and, along with several of his ministers, held a cabinet meeting underwater. Nasheed hoped to give the world a sense of its collective future. At an event at Columbia Law School he later said: “You can drastically reduce your greenhouse gas emissions so that the seas do not rise so much. Or when we show up on your shores in our boats, you can let us in. Or when we show up on your shores

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2019

Something is happening out there in the dark fields of “the discourse.” Incoherence is now a virtue. Rather than irony, modesty, discernment, ambivalence, or the mental sprightliness needed to parse conflicting views, a proud refusal to make solid arguments may be the cure for our divided times. Incoherence strikes a blow to partisan bickering and campus groupthink. Incoherence recoils from “tribes.” If an opinion sounds half-baked, or a claim brashly obtuse, it’s simply plowing through your pieties and wrenching open your padlocked mind. Incoherence is courage, incoherence is pluralism, incoherence is an ideological opera full of swordfights and forbidden love.

- excerpt • June 20, 2019

In the dark of the night of July 19, AD 64, a fire broke out in the slums of Rome and, swept along by vicious winds, devastated the town, leveling several districts entirely. The fire burned for six days, died down, was reignited, and burned for three more. Hundreds of people were killed; many more were left destitute and homeless.

- review • May 23, 2019

Years ago, I was shopping for a dinner party with my roommate. Our Chicago neighborhood—white ethnic and racist turned gentrified—hadn’t flipped enough to produce a decent seafood counter, so we found ourselves at the Jewel-Osco on Canal, blocks away from Maxwell Street. Witnessing this odd duo (me, black and from the south suburbs; my friend, first-generation Polish from the northwest suburbs), the clerk eyed us from behind the counter. Wrapping up our order in plastic, he asked, “So, where are you from?”

- print • Apr/May 2019

A specter is haunting the straight white liberal sixtysomething American dad—the specter of his damn socialist kids. A generation that grew up eating Cold War propaganda with their cornflakes confronts one in which socialism regularly outpolls capitalism, and it’s happening across the breakfast table. New Yorker writer Adam Gopnik’s new book, A Thousand Small Sanities: The Moral Adventure of Liberalism, is a manual for the dad side, a work of rousing reassurance for open-minded men who are nonetheless sick of losing political debates to teenagers whose meals they buy.

- print • Apr/May 2019

Bhaskar Sunkara’s Socialist Manifesto begins by entering an imaginary world. It’s 2018 and “you” are a die-hard fan of Jon Bon Jovi, “the most popular and critically acclaimed musician of this era.” So devoted are you to the singer-songwriter that you’ve found work at the pasta sauce factory his father owns in New Jersey. The job isn’t great, but it’s better than nothing. After a year, your wages rise from $15 an hour to $17, a 13 percent increase that fails to match your recent 25 percent increase in productivity; meanwhile your colleague Debra, who’s been working there for three

- print • Apr/May 2019

We’ve had half a century with The Second Sex, The Dialectic of Sex, Sexual Politics, and all the rest, yet straight men of letters still regard their fossilized sexism and quotidian horniness as windows into existential wisdom. Hard again! the male author marvels while streaming free porn in his book-lined office. What does it all mean? These are the inquiries of those who refuse to read feminists: How would a nerdy man have power over a pretty woman if she’s the one making him want her? How could a man be accused of disrespecting women when he’s so awestruck by

- print • Apr/May 2019

“I never pretended to be an expert on millennials,” writes Bret Easton Ellis halfway through White, and the reader desperately wishes this were true. Ellis is best known for American Psycho, the controversial 1991 cult novel about an image-obsessed Wall Street serial killer; the film adaption would star Christian Bale as psychotic investment banker Patrick Bateman. Following several increasingly metafictional novels and a few bad screenplays, White is Ellis’s first foray into nonfiction, and the result is less a series of glorified, padded-out blog posts than a series of regular, normal-size blog posts. Mostly, Ellis hates social media and wishes

- print • Feb/Mar 2019

When did Facebook start to seem evil? Was it last March, when United Nations investigators accused the platform of enabling the ethnic cleansing of the Rohingya minority in Myanmar? Or was it a few days after that, when it was revealed that the consulting firm Cambridge Analytica had harvested millions of people’s personal data to target votes, momentarily sending Facebook’s reputation (and stock) plummeting? Or in 2014, when researchers revealed that they had conducted a massive psychological experiment on nearly 700,000 users—without their consent—to determine whether manipulating feeds to display more depressing content would make some people sadder? (It did.)

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2018

DeRay Mckesson is a frustrating figure. I don’t mean Mckesson the person, but rather Mckesson the persona, which is what you become once you have achieved his level of visibility. In the span of about four years, Mckesson, an educator and activist associated with Black Lives Matter, has gone from around eight hundred Twitter followers to more than a million. One of those followers is Beyoncé. To give a sense of how big of a deal this is, it must be noted that Beyoncé follows only ten accounts—and none of them belong to her husband, Jay-Z. Mckesson was photographed alongside

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2018

The first piece in The Souls of Yellow Folk, the collection of Wesley Yang’s journalism, goes in with a bang. “The Face of Seung-Hui Cho,” Yang’s 2008 essay on the mass shooter of Virginia Tech, is a remarkable attempt to trace the author’s kinship with a young man who, one year earlier, had killed thirty-two people and then killed himself. Outlining Cho’s abysmal, toxified, embittered half-life, Yang describes his own as well. Raised American, both have inherited an unfortunate legacy: In the home of the brave, their meek yellowish faces have disqualified them from all human consideration. Their efforts at

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2016

Cody Wilson was a twenty-four-year-old law student when in early 2012 he realized he could unite his two strong interests, open-source software and the right to bear arms. By distributing digital blueprints for a handgun, he and his friends would allow anyone with a 3-D printer to manufacture his own “Wiki Weapon.” As soon as he conceives it, Wilson imagines himself on the news. “And now we turn to another story, seemingly out of the pages of science fiction,” he fantasizes. “Three-dimensional printable guns, made at home.”