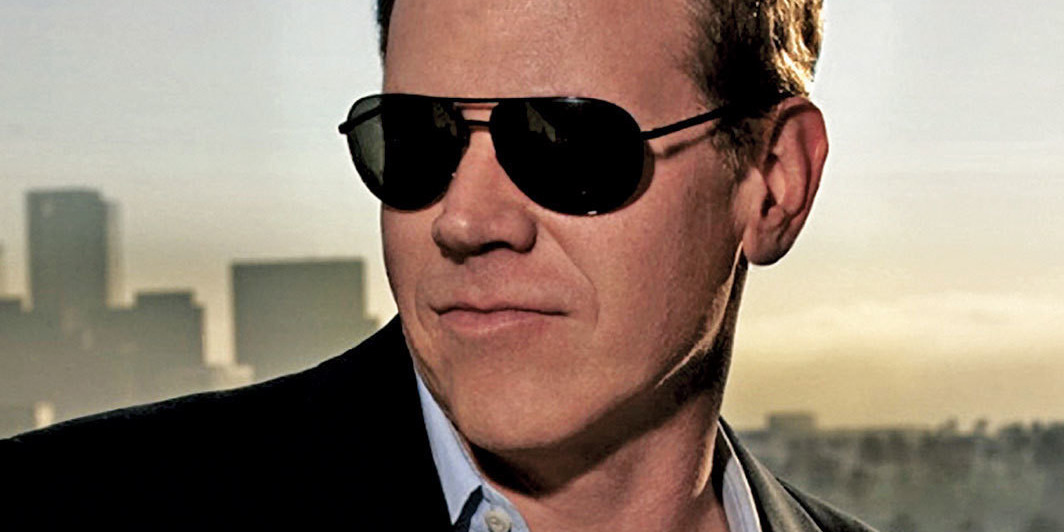

“I never pretended to be an expert on millennials,” writes Bret Easton Ellis halfway through White, and the reader desperately wishes this were true. Ellis is best known for American Psycho, the controversial 1991 cult novel about an image-obsessed Wall Street serial killer; the film adaption would star Christian Bale as psychotic investment banker Patrick Bateman. Following several increasingly metafictional novels and a few bad screenplays, White is Ellis’s first foray into nonfiction, and the result is less a series of glorified, padded-out blog posts than a series of regular, normal-size blog posts. Mostly, Ellis hates social media and wishes

- print • Apr/May 2019

- print • Feb/Mar 2019

When did Facebook start to seem evil? Was it last March, when United Nations investigators accused the platform of enabling the ethnic cleansing of the Rohingya minority in Myanmar? Or was it a few days after that, when it was revealed that the consulting firm Cambridge Analytica had harvested millions of people’s personal data to target votes, momentarily sending Facebook’s reputation (and stock) plummeting? Or in 2014, when researchers revealed that they had conducted a massive psychological experiment on nearly 700,000 users—without their consent—to determine whether manipulating feeds to display more depressing content would make some people sadder? (It did.)

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2018

DeRay Mckesson is a frustrating figure. I don’t mean Mckesson the person, but rather Mckesson the persona, which is what you become once you have achieved his level of visibility. In the span of about four years, Mckesson, an educator and activist associated with Black Lives Matter, has gone from around eight hundred Twitter followers to more than a million. One of those followers is Beyoncé. To give a sense of how big of a deal this is, it must be noted that Beyoncé follows only ten accounts—and none of them belong to her husband, Jay-Z. Mckesson was photographed alongside

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2018

The first piece in The Souls of Yellow Folk, the collection of Wesley Yang’s journalism, goes in with a bang. “The Face of Seung-Hui Cho,” Yang’s 2008 essay on the mass shooter of Virginia Tech, is a remarkable attempt to trace the author’s kinship with a young man who, one year earlier, had killed thirty-two people and then killed himself. Outlining Cho’s abysmal, toxified, embittered half-life, Yang describes his own as well. Raised American, both have inherited an unfortunate legacy: In the home of the brave, their meek yellowish faces have disqualified them from all human consideration. Their efforts at

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2016

Cody Wilson was a twenty-four-year-old law student when in early 2012 he realized he could unite his two strong interests, open-source software and the right to bear arms. By distributing digital blueprints for a handgun, he and his friends would allow anyone with a 3-D printer to manufacture his own “Wiki Weapon.” As soon as he conceives it, Wilson imagines himself on the news. “And now we turn to another story, seemingly out of the pages of science fiction,” he fantasizes. “Three-dimensional printable guns, made at home.”

- print • Apr/May 2018

February’s test launch of Elon Musk’s new Falcon Heavy rocket was probably the most expensive and most glorious publicity stunt in the history of advertising: flame and smoke, and then videos of the space-suited mannequin in the cherry-red Tesla Roadster, David Bowie on the stereo, Hitchhiker’s “DON’T PANIC!” on the dashboard screen. Behind this promotion was the promise that Musk’s company SpaceX will soon be sending colonists to the planet Mars. But although the car is on a trajectory that will pass the orbit of Mars later this year, it won’t get anywhere close to the Red Planet, and the

- print • Apr/May 2018

While #MeToo has exposed the pervasiveness of sexual abuse in a handful of high-profile industries, its priorities have so far reflected broader social hierarchies, giving outsize attention to the experiences of a privileged minority. In a Day’s Work shows us what harassment looks like outside Hollywood and the Beltway. A journalist at the Center for Investigative Reporting, Bernice Yeung has been on this beat for years, producing necessary, unglamorous exposés of the abuse suffered by low-wage laborers—mostly immigrants, mostly women—who are particularly vulnerable to sexual violence at work. Focusing on farmworkers, caregivers, maids, and janitors, Yeung’s investigation takes us into

- print • Feb/Mar 2018

Kabul in the summer of 1996 was under siege. A little-known force of young militants had surged north from their base in the south. For months, they had camped just beyond the city limits, raining shells on the capital almost daily. They called themselves religious “students”—or in the local Pashto, Taliban.

- print • Feb/Mar 2018

If there was one book impossible to escape during the eternal election of 2016, it was J. D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy. The Ohio native’s “memoir of a family and culture in crisis,” which detailed his dismal childhood with a substance-abusing single mother and his ascension, through hard work and education, into the ranks of the coastal elite, received rapturous praise upon its publication. Liberal and conservative commentators alike seized on its narrative and setting as a key to the candidacy and election of Donald Trump. In Vance, they discovered a trustworthy local interpreter from Trump Country—one willing to confirm that

- review • January 9, 2018

A number of my fellow journalists are saying privately and publicly that Michael Wolff’s book is no big deal—“nothing we didn’t know already.” This response makes me think of people who see some piece of modern art, a Jackson Pollock or an Ellsworth Kelly, and say, “I could do that.” Yeah, but did you? I don’t […]

- print • Dec/Jan 2018

Anesthesia has been around for over 170 years, and in spite of its inherent drama it’s impressively nonlethal. Current estimates place the death toll at about one in two hundred thousand or even one in three hundred thousand, which means—according to the earnest nonprofit the National Safety Council—that you or I are more likely to die from insect stings, “excessive natural heat,” or “contact with sharp objects” than either of us is from being put under. Properly supervised anesthesia is not only exceedingly safe but also ubiquitous, and necessary for a slew of lifesaving and life-improving procedures. Yet in these

- review • October 11, 2017

We first meet Dix Steele, the star of Nicholas Ray’s 1950 Hollywood noir In a Lonely Place, as he pulls his car up to a stoplight on a dark Los Angeles street. From the vehicle next to him, a blonde woman addresses him by name—she seems to know him, but Dix isn’t having it. When she tells Dix that she starred in the last picture he wrote, the screenwriter replies tartly, “I make it a point never to see pictures I write.” Because Dix is played by Humphrey Bogart, the line comes across with a wry charm, but because he’s

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2017

The word totalitarianism has an ominous ring. At the height of the Cold War, in the 1950s and ’60s, Western social scientists began using it to describe the political structure of the USSR, as part of an ideological effort to equate the Soviet system in general, and Stalinism in particular, with Nazism. That effort was very successful. The “totalitarian model” gained such a powerful grip on people’s imaginations that when, in the ’80s, a new generation of scholars began poking holes in it, they took a pummeling, accused of being Communist sympathizers or apologists for Stalin’s crimes.

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2017

In 2007, Suzy Hansen was a reporter at the New York Observer. Hansen was twenty-nine; she had grown up in a small town in New Jersey and moved to New York City after college. When she first arrived, New York seemed like the center of the world, but in the years after September 11 it began to feel increasingly provincial, both feverish and inward-looking. The liberal journalists she knew were “extremely arrogant,” convinced of their moral superiority to the Bush-era Republicans but strangely indifferent to the wars being fought in their names in Iraq and Afghanistan. Caught up in a

- print • June/July/Aug 2017

It’s April 16, and Turkey is voting on a constitutional referendum that may allow its president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, to drastically increase his powers. It’s the most significant day in the modern history of my country, and I’m watching events unfold on my phone screen in Zagreb, Croatia, where I now live. (Rather than deal with the constant threat of imprisonment or of having my passport confiscated, I chose to get out a few months ago.) In Turkey, the streets are full: People know that this is, in effect, the last chance to prevent a dictatorship.

- print • June/July/Aug 2017

While reading Trita Parsi’s history of the US-Iran nuclear negotiations, it’s hard not to wonder with horror—at every complicated twist and turn of the proceedings—how Donald Trump would manage a similar ordeal. The sometimes excruciating detail of Parsi’s book reminds us of all the tiny acts of diplomacy—and anti-diplomacy—happening right this very second behind closed doors, ones that could, in the case of Iran, be leading to unnecessary war.

- print • Apr/May 2017

How did South Korea grow from one of the poorest countries in the world circa 1960 into the one that has the eleventh-largest economy today? The “Miracle on the Han” has been studied by economists in search of the secret sauce to apply to other impoverished and war-torn nations. Most agree that Korea’s success stemmed from the authoritarian policies of Park Chung Hee, the general who came to power via a military coup in 1961 and was president until 1979, when he was assassinated. His playbook has been emulated by regimes around the world: an anticommunist government that keeps tight

- print • Apr/May 2017

The Osage were warriors, buffalo hunters, harvesters, farmers—one of the great nations of the Great Plains. Europeans who encountered them early on described them as uncommonly tall, well-built, imposing: The “finest men we have ever seen,” Thomas Jefferson said in 1804, after meeting a delegation of Osage chiefs in the White House. By the time of Jefferson’s death, they’d been stripped of their ancestral lands—”forced to cede nearly a hundred million acres,” David Grann writesin Killers of the Flower Moon, “ultimately finding refuge in a 50-by-125-mile area in southeastern Kansas.” And in the years immediately following the Civil War, American

- print • Apr/May 2017

Melissa Goldbach accused her child’s father of having sexually assaulted her during their custody handoff in a Wisconsin parking lot in 2011. When confronted with security footage of events different from those she described, she conceded that the sex had been consensual. In late 2013, North Carolinian Joanie Faircloth began to make numerous internet comments and social-media posts claiming that indie musician Conor Oberst had raped her when she was sixteen. After about six months, in a notarized recantation, she wrote: “I made up those lies.” “That part’s not true,” Carolyn Bryant Donham admitted over half a century after she’d

- print • Feb/Mar 2017

It didn’t take long following the first utterance of those dreadful four words almost no one expected to hear—president-elect Donald Trump—for political shock to give way to an onslaught of analyses of how an event so recently unimaginable had been hiding in plain sight. Like the banking crisis in 2008 and the terrorist attacks of 2001, the surprise was amplified by the sense that all our certainties—political, economic, cultural—seemed to melt before our eyes. While some commentators focused on the short term and the days, weeks, and months leading up to the election, most played the long game, mining the