Few writers have enjoyed a life as illustrious and a career as versatile as Gore Vidal. A self-taught intellectual and the author of twenty-five novels and eleven essay collections—among them Julian (1964), Myra Breckinridge (1968), Creation (1981), Lincoln (1984), Screening History (1992), and United States: Essays 1952–1992 (1993)—Vidal appears to have done it all. He has run for seats in both the House and the Senate, written for the Broadway stage and both the small and big screens, acted in films, drawn the blueprint for what would become the Peace Corps, appeared regularly on the late-night talk-show circuit, and known many of the last century’s major historical figures, from Huey Long, Eleanor Roosevelt, and Amelia Earhart to Tennessee Williams, Federico Fellini, and Johnny Carson. Vidal was born into an enchanted legacy: His grandfather was Oklahoma’s first elected senator (and, Vidal claims, a distant relation of former vice president Al Gore); his father, an aeronautics engineer, served as the director of air commerce in the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration; and his mother, whom Vidal describes as a “flapper very like her coeval, Talullah Bankhead,” was once married to financier Hugh Auchincloss Jr., Jackie Kennedy Onassis’s future stepfather.

Vidal was hardly one to rest on his family laurels—he is one of our most prolific writers, praised by Harold Bloom as “a masterly American historical novelist.” The provocateur is, perhaps, more celebrated for his erudite, witty, often-trenchant essays on literature and politics, which have earned him awards (not to mention the scorn of the right wing) and established him as one of the fiercest critics of what he calls the “United States of Amnesia.” Vidal has clashed over politics with many literary and political figures, most notoriously William F. Buckley Jr. During the 1968 Democratic Convention, the two debated on an ABC news program. At one point, Vidal called Buckley a “pro-crypto-Nazi.” Buckley snapped back, “Now listen, you queer, stop calling me a crypto-Nazi or I’ll sock you in your goddamn face and you’ll stay plastered.” Vidal also waged a cold war with the New York Times Book Review, which shut him out following the 1948 publication of The City and the Pillar, considered to be the first explicitly gay American novel.

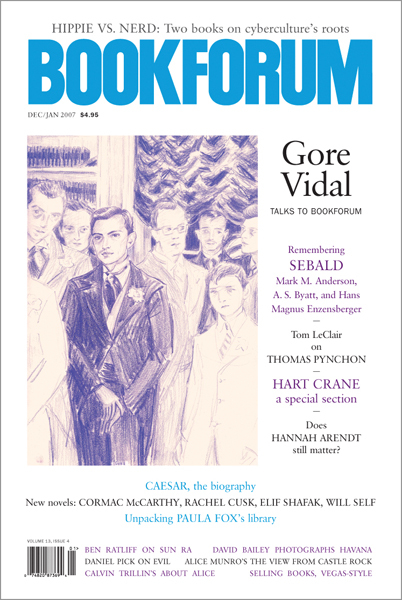

Point to Point Navigation: A Memoir, 1964 to 2006 (Doubleday), doesn’t quite pick up where Palimpsest (1995) left off—the aperture expands to include all eight decades of his life. After years of living on and off in Ravello, Italy, with his longtime companion, Howard Auster, who died in 2003, he has returned to their home in Los Angeles. Vidal ruminates over his own mortality in the wake of Auster’s death; muses over his passion for film, which began in childhood; and details the history of the political conspiracies and hypocrisies that have kept him engaged in politics, as a two-time candidate and currently as an activist. We spoke by phone in October, the day after his eighty-first birthday, about the celebrity and fate of the American novelist, the innumerable battles he’s faced over the years, and the true nature of irony. —KERA BOLONIK

BOOKFORUM: You write in Point to Point Navigation that you were once a “famous novelist,” by which you don’t mean you’ve stopped writing novels. You say, “To speak today of a famous novelist is like speaking of a famous cabinetmaker or speedboat designer.”

GORE VIDAL: Yes. There’s no such thing as a famous novelist.

BF: But what about a writer like Salman Rushdie?

GV: He’s moderately well known, but he’s not read by a large public. He’s very good, but “famous” has nothing to do with being good or bad.

BF: A few critics have declared the American novel dead.

GV: I don’t think the novel is dead. I think the readers are dead. The novel doesn’t interest anybody, and that’s largely because there are no famous novelists. Fame means that you are touching everybody or potentially touching everybody with what you’ve done—that they like to think about it and talk about it and exchange views on it.

BF: Novelists used to work the nightly talk-show circuit. It’s hard to believe that there was a time in this country when writers were regarded as celebrities.

GV: I started all of that. I was the first novelist to go on television back in the ’50s, on The Jack Paar Show and The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson.

BF: You’ve had many careers and identities, often simultaneously: essayist, novelist, actor, screenwriter, playwright, political candidate. Which best describes your public persona?

GV: It depends on what’s happening that season. At the moment, I’m a politician. I’m trying to raise money for the Democratic Party, so I go around making speeches, trying to get audiences for candidates. The only reason I ever did television had nothing to do with books. It had to do with politics. I ran for office in 1960 in New York, and since I did not have corporate America behind me to pay the bills, I had to go on whatever television I could get. That’s how I started out with Mr. Paar.

BF: You came very close to winning a congressional seat, representing the Mid-Hudson Valley in New York State.

GV: Yeah. Well, I doubled the vote, anyway.

BF: If you had won a seat in Congress, what would have become of your literary career?

GV: I was prepared to put it on hold for a while, but then I realized the whole thing was about money. When I went into the Senate primary in California back in 1982, Senator Alan Cranston told me, “Do you know what you’re getting yourself involved in?” And I said, “Of course I do.” He said, “Suppose you get elected to a six-year term. For every week of the six years that you serve your first term in the Senate, you have to raise ten thousand dollars if you plan to run again.” I realized then that I was not going to do that [laughs].

BF: Still, do you regret not getting elected to public office?

GV: No. I didn’t want to spend all my time on the telephone trying to raise money for a campaign. By 1980, that was the entire game, nothing else. You’re not elected because people think you’re any good. You’re elected because you can buy the ads. It’s about marketing—marketing junk. You know the next move is dictatorship. This is what happens.

BF: You enjoyed a friendship with former first lady Eleanor Roosevelt, with whom you discussed your idea for a volunteer army, a notion that would eventually evolve into the Peace Corps. You suggested your plan to John F. Kennedy, who was campaigning for president. Did he ever give you credit?

GV: Of course not. It was part of my regular stump speech around the Twenty-ninth District of New York State, and it was a very popular notion. This was in the days of the draft, and we were getting involved with wars, starting with Korea. I said, instead of drafting people into the military, why not have an optional plan in which they can work in foreign countries or in the United States doing good works, and give a year or two to the country, and then finish their education? I thought it was a good idea, and Mrs. Roosevelt was very enthusiastic about it. I sent all of my notes on it to Jack Kennedy, who was at that moment campaigning in San Francisco. I think that’s where he slid it into his stump speech.

BF: Over the years, you counted among your friends Paul Bowles, Tennessee Williams, Paul Newman, Saul Bellow, Greta Garbo, and Rudolf Nureyev, to name a small sampling. Who were among the most influential people in your life?

GV: You get to know a number of people over time, and some are more central to you at some times and less so at other times. When I was politicking, Eleanor Roosevelt was very central, and I relied on her steadiness. She was an inspired politician and very tough—she was not a kindly old granny at all. She was tough as nails, and I admired her a great deal, personally and politically. As for writers, if you’re a writer yourself, you don’t have mentors. Maybe when you’re very young, but I never did. I never went to university, so I never had the opportunity to be taught by people who thought they knew what literature was. This was a great blessing.

BF: What about your literary peers?

GV: I learned playwriting from going to Tennessee’s rehearsals.

BF: Did you have any sense of the impact The City and the Pillar would make when it was published in 1948?

GV: I did, I did. And then I was blacked out by the New York Times.

BF: They refused to review your next five books. Were you ever hesitant to publish the book for fear of your readers’ and critics’ reactions?

GV: No. I’ve never run from a fight. I like battle. And I thought the whole subject had been so badly treated. My entire life was spent in boys’ schools, ranch schools. Then I was three years in the army in World War II. I knew quite a lot about how the world worked, and this American hysteria about sex got on my nerves. It still does. Look at this Mark Foley thing. It’s just bad education. We have a bad culture, let’s face it. It starts with the public school system, which is a disaster for people who do not come from well-to-do families. Students don’t learn American history, they don’t learn much about the world, they don’t learn languages. They’re kind of out of it.

BF: You’ve had a history of going head-to-head with the New York Times Book Review—The City and the Pillar was only the first time. During the ’50s, their critics raved about a mystery trilogy you penned under the pseudonym Edgar Box while ignoring your serious fiction. What’s worse, they panned the mystery trilogy when it was reissued in 1978 under your own name. Later, they trashed Myra Breckinridge after they made a vow to you that they wouldn’t review it.

GV: Oh yeah. They always ran on bad faith, you know?

BF: Did you ever resolve your relationship with them?

GV: I’ve had pleasant relations with occasional Sunday Book Review editors. Rebecca Sinkler was an extremely nice woman, and she was the first and the only woman to run that publication. We got along very well, and I actually did a couple of pieces for her. But the rest of the time, they were out there fag bashing. It was an ugly paper. They’re not as bad now as they used to be—considering the people who work for them now, they couldn’t be.

BF: Did your experiences with the New York Times Book Review affect your literary criticism?

GV: I was always an essayist. The literary essayist is a very enticing role for a writer. And I had to protect myself, so they knew that if they attacked me gratuitously, I’d be back there pounding them.

BF: You had a powerful venue in the New York Review of Books.

GV: I should say so. That came along at exactly the right moment for me.

BF: Norman Mailer shares your love of a good fight, but he likes to get physical. He went on The Dick Cavett Show to brawl with you, but you refused. As the story goes, he tried to pick it up again a few years later, when he threw a drink in your face. You replied, “Once again, words fail Norman Mailer.”

GV: [laughs] We’re friends now.

BF: How did that happen?

GV: Mailer asked if I would appear in his production of Don Juan in Hell playing the devil. He was playing Don Juan, and Susan Sontag was playing Donna Anna. We did it to raise money for the Actors Studio.

BF: So the play was his olive branch?

GV: No. He was the president of PEN [1984–86] and was always trying to get me to do speeches and do this and do that. At one point, he wanted me to succeed him as head of PEN. I told him, I don’t like writers and I don’t want to live in New York.

BF: What do you make of literary spats that turn into public brawls? Two years ago, Stanley Crouch slapped Dale Peck for writing a scathing review of his novel, and Richard Ford spat at Colson Whitehead for the same crime.

GV: I don’t know anything about those things. I’m not interested. You can go from one end of my memoirs to the other—two volumes—and you don’t find any of this stuff.

BF: Is there one book that you believe best evokes who you are as a writer?

GV: The one that I wish everybody would read is Creation. I spent years on that book, and anyone who reads it from beginning to end will learn about the Buddha, about Confucius, about Zoroaster, about Mahavira and the Jains. It’s very popular in countries which offer, more or less, classical educations. In the US, practically nobody knows about it because it’s not about family life, it’s not about marriage and divorce. Those seem to be the only subjects that American writers touch.

BF: Your writing career extends to the silver screen, particularly your script for Ben-Hur. You wove in a homoerotic story line that suggested a past romance between Ben-Hur and Messala, but this fact was supposed to be kept secret from Charlton Heston. Was there a thrill in doing that?

GV: No, it was necessity. The script just didn’t work. I had to explain why on earth they’re feuding for four hours. The romantic subtext worked like a dream.

BF: Charlton Heston, of whom you wrote directing him must be like trying “to animate an entire lumberyard,” refused to acknowledge your contributions to the script, insisting that the director, William Wyler, rejected your suggestions.

GV: Charlton Heston told lies. I had as little to do with him as possible. He was also the last choice of the director and the producer. They were stuck with him. And then it turned out he wasn’t as good as Stephen Boyd, who played the Roman. But that was not my problem. I was not producing it. I was there to try to dramatize an old and rather junky story.

BF: In the new memoir, you say that, in today’s culture, “where literature was movies are.” Are there films that rank with good literary fiction?

GV: I don’t think you could ever compare the two. Literature is where it is and totally different, and movies are a peculiar art form. Film is the only art form that lacks mind, because there’s no way the individual writer can supply it with ideas. Directors make their contributions, some better than others. Film editors probably do the most work toward creating what you see up on the screen. And they are working quite separately from whatever the movie may be about. They’re just trying to get images straight. It’s not a medium you can invest with the sort of ideas that work in a novel or even poetry.

BF: In the final pages of Point to Point Navigation, you note that “irony has never had an easy time of it in our American version of English” and that much of what you write is ironic. Is our culture deaf to irony?

GV: Pretty much. Irony requires—I’ll have to resort to rather clichéd words—a rather nuanced view of the world, of reality and false notes versus true notes. Some people are better at getting it than others, and some are better at employing it. In the book, I use the example of catastrophic irony in the midst of a murder plot, one that the Kennedys got caught in. And that really is spectacular.

BF: That’s a very profound example of irony, but is that the last example we’ve witnessed in our recent history?

GV: I don’t think we’ve ever seen it before. We didn’t see it happen. We only know in retrospect now the plan to kill Castro while the Mob out of New Orleans was simultaneously getting ready to kill Jack Kennedy. Some of the people are overlapping. The CIA had always used mobsters to try and get Castro. And there’s the same cast again, all reshuffled. Jack was so suspicious of the CIA after the Bay of Pigs that he didn’t want them involved in “C day,” which was supposed to be the murder of Castro, so he put that on the Department of Defense. They all used the same bunch of hoods, from Chicago, Dallas, Tampa, so indeed it is ironic that the same cast was selected each time to do its dirty work.

BF: Throughout your memoir, you refer to Montaigne and memory and, not least of all, its lapses. Montaigne says, “I now grow forgetful. Names refuse to come when bidden.” From the pages of your memoirs, you would seem to forget very little. Do you write for fear of forgetting?

GV: Well, the physiology of memory, it’s not what most people think it is. If you break your leg when you’re ten years old and you suddenly think about it when you’re forty, you’re not going to play a tape in your head. It’s not like the movies or the editing of film. Memory is quite different. What you remember is not the event, what you remember is the last time you remembered it. Hence my title Palimpsest—it’s one memory on top of another. Things can get very, very skewed over the years, obscured. Memory is a struggle, and you just hope you still get it approximately right, but you’ll never get it precisely right because there is no way of doing that, the brain doesn’t work that way. It’s not as though you have a lot of tapes in your head that you can press a button and play. What you have is a theater. I think every writer has so many actors in his head, and when he wants to remember a book or something, it’s like staging a play in your mind. Some writers have a huge cast of characters in their head that can work for them, Shakespeare being the great example. Somebody like Tennessee Williams, he had about a dozen people in his theater, and he had good parts for a lot of them. And some writers only have one [laughs]. I won’t name names.